Since its founding in 1521, Mexico City was concentrated within a defined area, surrounded by towns and rural expanses. Architectural and housing patterns during the colonial period remained largely consistent for centuries. Significant changes in the city’s morphology began in the 19th century. Following Mexico’s Independence, successive governments delineated the boundaries of the Federal District: Mexico City served as the administrative center, while beyond it lay estates and ranches grouped into “barracks,”11 (Español) Sánchez Martínez, M. La Ciudad de México en la cartografía oficial del Porfiriato: Los planos oficiales de la Ciudad de México de 1891 y 1900. Universidad Nacional Autónoma Metropolitana: 2016: 5. accessible only by traversing long, barely marked paths. Among various national development programs, the government focused on attracting substantial foreign migration to populate the capital and commercial hubs.

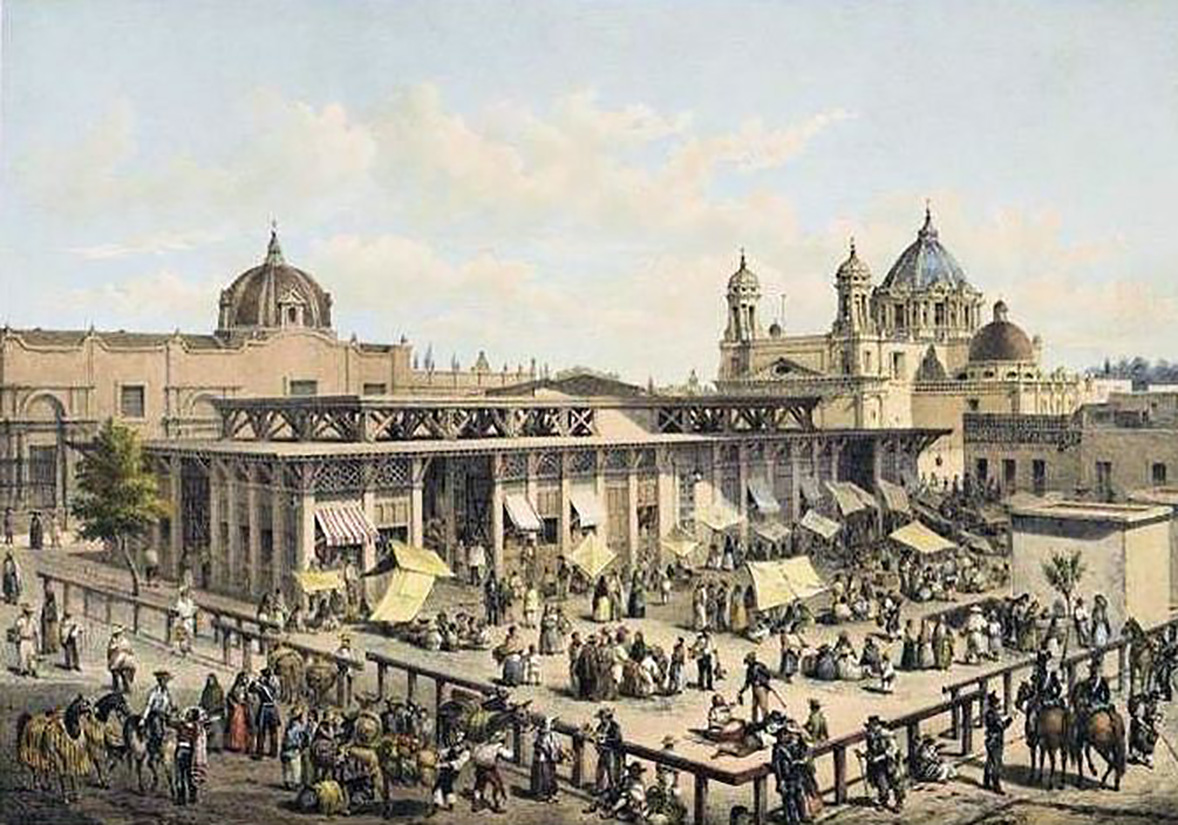

Within this context, several French families settled on agricultural land between what are now Article 123, Eje Central, Arcos de Belén, and Bucareli streets, with city council permission. Like many migrant communities, they spurred significant commercial activity soon after their arrival. By the 1850s, this area was fully subdivided in the style of Parisian arrondissements, hosting establishments such as the Iturbide Market, the New Mexico Theater, public baths, and various commercial premises. Residents began referring to this area as the “French colony,” using “colony” to denote a “group of natives from a country, region, or province living in another territory.”22 (Español) Real Academia Española. (2001). Diccionario de la lengua española (22.a ed.). Consultado en http://www.rae.es/rae.html This term soon extended from describing the community to the territory itself, marking the linguistic origin of what we now call “colonias.”33 (Español) Más adelante, el ayuntamiento cambiaría el nombre oficial de ésta a colonia Nuevo México debido al estallido de la Guerra de los Pasteles y a un impulso nacionalista del Estado.

A few years later, the Reform Laws were decreed, aiming to expropriate ecclesiastical assets and thus give the State complete freedom to modernize the city44 (Español) En particular las Leyes de desamortización —Ley Lerdo del 25 de junio de 1856— y nacionalización de bienes eclesiásticos —promulgada el 12 de julio de 1859. and address the housing demands prompted by demographic growth. Consequently, about 48% of the city’s urban land was put into commercial circulation,55 (Español) Anda, E. (2013). Historia de la arquitectura mexicana (p. 193). Barcelona: Gustavo Gili: 193. sparking a wave of speculation and a new territorial order reflected in various ways of living, moving, and social interaction.

Businessmen with political connections created companies to subdivide large tracts of land adjacent to Mexico City, expanding the term “colonia” to this new urban model. The government also seized church buildings to open avenues and repurpose them for public use.66 (Español) Se adaptaban entre otros programas para ser escuelas, hospitales y vivienda. In 1857, the colonia de los Azulejos emerged from 16 properties behind what is now the “Casa de los Mascarones.”77 (Español) Alba González, M. (2015). Vejez, memoria y ciudad. Editorial Miguel Ángel Porrúa. That same year, Fernando Somera purchased the Ejido de la Horca and established the colonia de los Arquitectos (Architects’ neighborhood), initially intended for members of the San Carlos Academy but later sold to wealthier individuals. To the northwest, the Flores family acquired the Santa María ranch to build and sell residential houses. Surveyor Francisco Jiménez incorporated the newly developed Los Azulejos colony into a grid of 56 blocks, each with 20 lots.88 (Español) Reyes Fragoso, A. (agosto 2006). “Santa María la Ribera, colonia centenaria”. El Universal.

By 1861, Santa María la Ribera was officially recognized as a colonia. Despite lacking services initially, residents quickly organized to pave the streets. By the early 20th century, it had grown into a significant residential area meeting the needs of small merchants, state workers, professionals, and intellectuals.

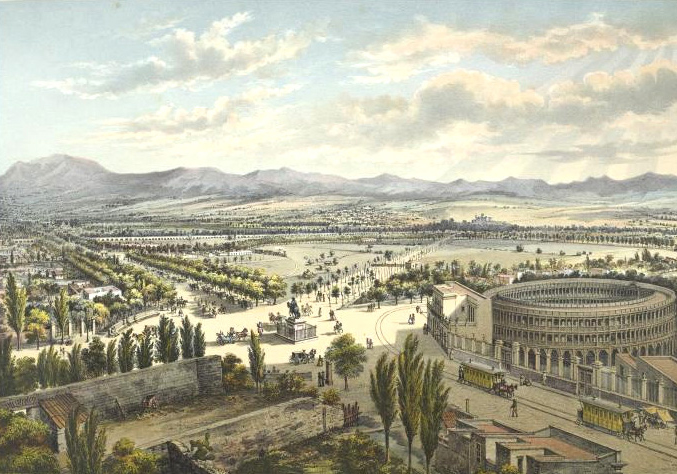

Alongside these developments, Maximilian of Habsburg chose the Chapultepec fortress in Tacubaya as his official residence. The area, known for its advantageous position against weather threats, attracted government officials and the wealthy, leading to the construction of large haciendas and estates. This influx necessitated the development of communication routes between Tacubaya and the city, culminating in the establishment of the first regular passenger train system, eventually reaching Tlalpan, San Ángel, Cuajimalpa, Azcapotzalco, and Villa de Guadalupe.99 (Español) De Gortari Rabiela, R., Hernández Franyuti, R. (1998) La Ciudad de México y el Distrito Federal: Una historia compartida. México: Instituto de Investigaciones Hisóricas José María Mora: 1998:

The Chapultepec Forest needed a direct connection to the Plaza de la Constitución, the political hub of Mexico City. Consequently, Maximilian of Habsburg commissioned the construction of what is now Paseo de la Reforma (originally Paseo de la Emperatriz). To avoid disrupting existing structures, the perimeter avenue started from Bucareli, a common entry point into the city. This new axis became a strategic artery, spurring the development of several new colonies along its sides. These colonies featured modern urban designs inspired by European and North American cities, characterized by wide boulevards and landscaped streets.

The population redistribution into new areas left many colonial houses in the Historic Center vacant. These, along with convents and other buildings, were repurposed into low-cost communal housing, a typology that had existed since the New Spain period. These small rooms, often with high ceilings, enabled the creation of makeshift lofts called “tapancos.” They typically featured communal patios for laundry and bathroom services. The Historic Center had the highest concentration of such neighborhoods, spread across areas like La Lagunilla, Mixcalco, San Miguel, San Antonio Abad, San Pablo, Santo Tomás, San Juan, Peralvillo, and La Merced.1010 (Español) Anda, E. (2013). Historia de la arquitectura mexicana (p. 193). Barcelona: Gustavo Gili: 196.

To the south, Tizapán, one of the eleven towns forming the municipal seat of San Ángel, became a significant manufacturing hub due to its proximity to a Magdalena River waterfall. The Nuestra Señora de Loreto paper factory (later known as Loreto and Peña Pobre) was established there in the 18th century. Later, in the late 18th century, textile factories such as La Abeja, La Alpina, and La Hormiga were built. To the north, worker housing was constructed, much of which still exists, reflecting the popular architecture of the time. These houses often incorporated workspaces offering various services.

1/

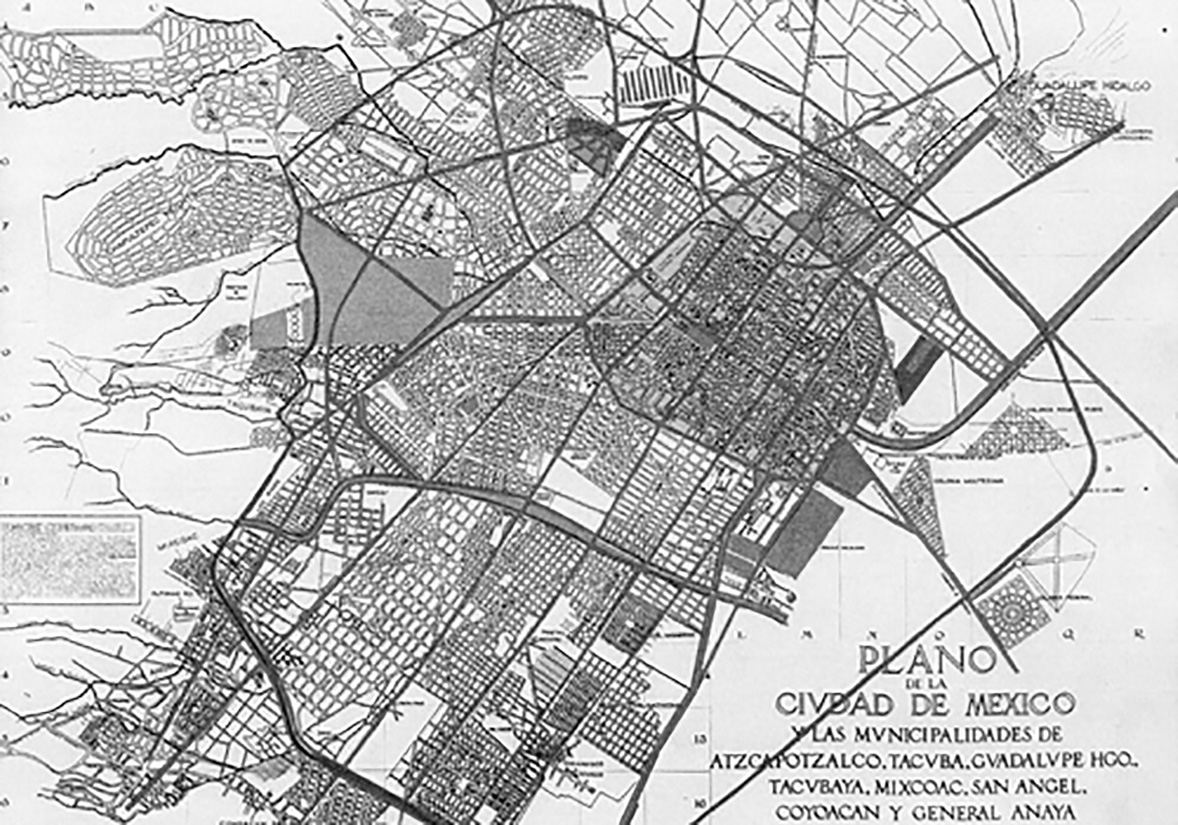

Porfirio Díaz’s early presidency marked an era of progress and modernization. Rapid economic development, fueled by robust commercial and industrial activities, enriched a privileged class. This led many private investors to buy cheap rural land, subdivide it, and transform it into valuable urban property. Between 1882 and 1910, over 25 subdivisions were developed.1111 (Español) Ribera Carbó, E. (2003). Casa, habitación y espacio urbano en México. Revista electrónica de geografía y ciencias sociales, Vol. VII, núm. 146(015). Disponible en: http://www.ub.edu/geocrit/sn/sn-146(015).htm Some catered to the middle and upper classes of merchants and professionals, while others were designed for working-class populations. These developments were largely investor-driven, with minimal government regulation. The government focused on building infrastructure, such as streets, highways, railways, and ports, and providing essential services like drainage, sewage, and public lighting. Additionally, new educational, scientific, and cultural institutions were established, encouraging Mexicans to utilize public spaces more.

The San Rafael neighborhood, also known as Cebollón, was established on land acquired by Tron, Signoret, and García.1212 (Español) Martinez Dominguez, Margarita G. (2011) La colonia de los Arquitectos a través del tiempo. México: Casa Juan Pablos. The lots attracted both wealthy families and middle-class individuals, fostering a rich social fabric and diverse architectural styles. Officially recognized in 1891, San Rafael featured everything from grand mansions to collective housing complexes. Private homes, often small houses or apartments along pedestrian streets, emerged as a blend of communal and private spaces, typically enclosed by iron fences.

One notable example is Privada Mascota, divided into Ideal, La Mascota, and Gardenias sections, each featuring central streets with landscaped medians. Commissioned by engineer Miguel Ángel de Quevedo for Ernesto Pugibet, owner of the prominent cigar company “El Buen Tono,” this complex was built near the factory to provide housing for its workers. The 174 homes for executives and senior managers were located on the perimeter for easy street access, while those for other workers lined the central streets of the three private sections.1313 (Español) Pardo, F. (junio 2013). Vivienda y tabaco. México: Arquine. https://www.arquine.com/vivienda-y-tabaco/

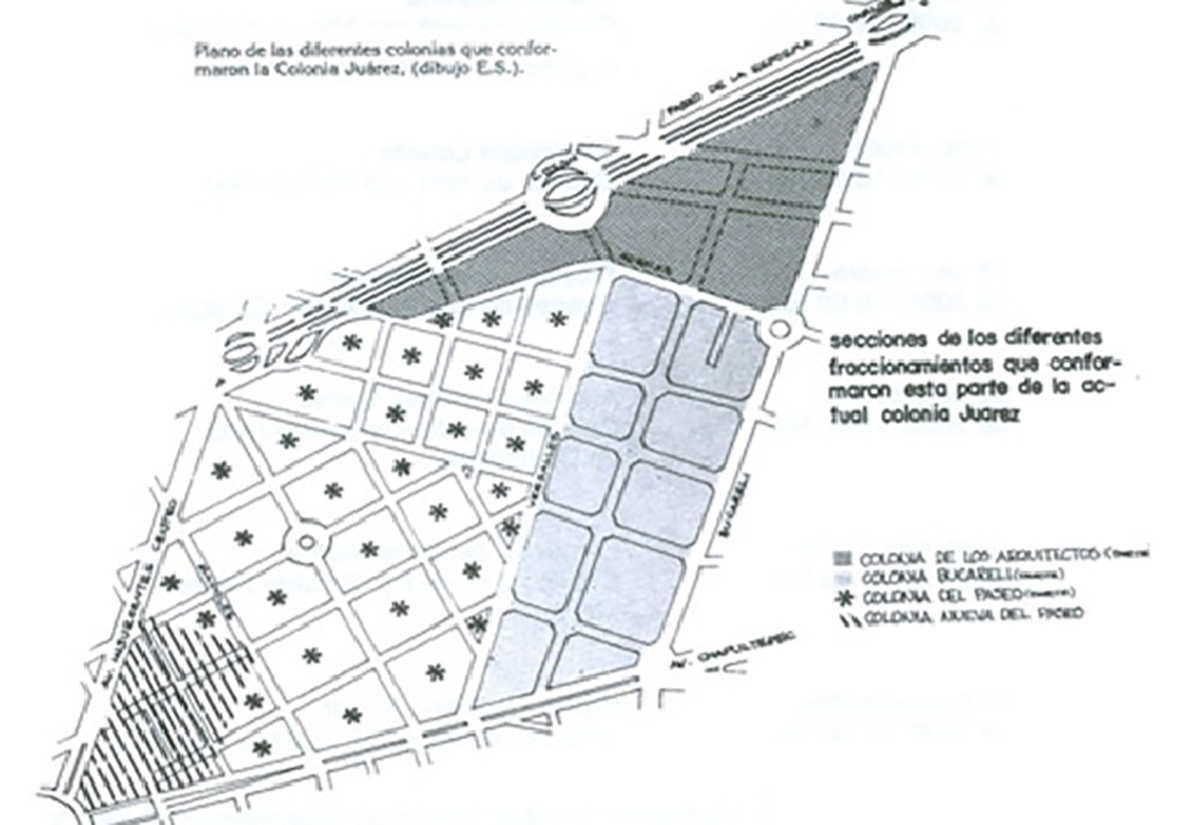

Since the mid-1870s, Rafael Martínez de la Torre began urbanizing an area known as Hacienda de la Teja. Adjacent to this were the Paseo and Paseo Nuevo neighborhoods. In 1898, these areas were integrated into a new neighborhood, although initially, only the layout of streets and subdivision of land were available. By 1904, the area was fully urbanized with basic infrastructure, thanks to investments from the Mexico City Improvement Company, owned by American businessmen, who named the colonia “Americana.”.1414 (Español) Almandoz Marte, A. (2002) Planning Latin America’s Capital Cities 1850-1950. Reino Unido: Routledge: 167. Two years later, in commemoration of Benito Juárez’s birth, the name was changed to Colonia Juárez.

Designed to house the upper classes, Colonia Juárez saw wealthy families constructing chalets and palaces on entire lots. These residences, eclectic in style, primarily imitated French and Belgian architecture but included influences from other regions and periods. They replaced the central patios typical of colonial architecture with front or side gardens, and the reception rooms and staircases became the focal points of the houses, characterized by their ostentatious proportions and elaborate coverings.1515 (Español) Ibid.

Following the development of Colonia Juárez, land from the Hacienda de la Condesa in Tacubaya was subdivided for commercial use. The first colony from these lands, laid out by the Escandón Barrón and Escandón Arango brothers, was organized orthogonally, adapting to the area’s topography and rivers, particularly La Piedad and Becerra to the south.1616 (Español) García Fernández, R. (2018) La colonia Escandón. Políticas urbanas y transformación socioespacial. Boletín De Monumentos Históricos, (38), 115-137. This neighborhood attracted bourgeois families who built villas and country houses, which later made way for iconic buildings like the Isabel complex, the Jardín building, and the Ermita Building.

Around the same period, the Guerrero colony was established through the sale of lots divided by Rafael Martínez de la Torre from the old San Fernando pantheon.1717 (Español) Revistavector.com.mx. (2019) Espacio de todos; las vecindades en la ciudad de México – Plataforma Vector.

Some lots were purchased by wealthy families, such as the Rivas Mercado and the Escandón families. However, others were intended for popular housing for the middle classes, marking the beginning of the neighborhood’s history. Similarly, the Morelos neighborhood, founded in 1884, exemplifies how the city began to populate with working-class neighborhoods. This colony, along with surrounding areas like Díaz de León and De la Bolsa, housed merchants, shoemakers, workers, and day laborers who developed a unique identity that persists today.

Nearby, “The Mexican City Property Syndicate Limited” proposed dividing the Indianilla land, partly managed by the tram company for storage and repair. Once approved, the streets of the Hidalgo neighborhood were laid out, but services were often neglected, leaving residents to organize and fund essential utilities like electricity, drainage, and security. This neighborhood was later renamed Doctors, reflecting the street names dedicated to famous doctors.

The emergence of automobiles as a new mode of transportation led to the redesign of existing streets and the creation of new avenues. Early in the 20th century, major roads like Insurgentes became axes for new colonies. One such neighborhood was La Roma, developed on the land of the Potreros de la Romita. Modeled after Colonia Juárez, it incorporated new elements like medians and plazas. These neighborhoods promised electric lighting, sanitation, water, and superior paving. By then, the numerical street naming system (north-south roads called streets and east-west roads called avenues) proved confusing. Thus, in 1904, the city council decided that naming streets after towns, events, and notable people would be more practical.1818 (Español) González Gamio A. (2019). La Jornada: Colonia con historia. [online] La Jornada.

Colonia Roma, heavily invested in by Edward Walter Orrin, owner and founder of the Orrin Circus,1919 (Español) Montes de Oca, P. (2015). Vida y milagros de… la colonia Roma. México: Algarabía. named its streets after the cities in Mexico where the circus was shown. The architecture embraced various historical styles like Gothic, Art Nouveau, and Art Deco, and incorporated Italian, French, and Arab elements.

In 1906, the old Carmelite orchard lands were divided to create the residential colony “Huerta del Carmen,” now Chimalistac. Meanwhile, the city center faced exponentially growing housing demand, land speculation, and the consolidation of banking systems enabling urban credit.

1/

The early years of the Revolution brought housing struggles, with social sectors affected by disparities from the Porfiriato organizing, and revolutionary leaders proposing strategies. Under Carranza’s leadership, tenant-supportive laws emerged. In early 1916, Justice Minister Roque Estrada decreed eviction trials could only be filed under specific conditions, like non-payment of rent over 25 pesos2020 (Español) Cohen, M. y Cohen, M. (1979). Política y vivienda en México 1910-1952. Revista Mexicana de Sociología, 41(3), p.769 and in November, rent controls were imposed on government-intervened properties, sparking reactions from tenant organizations.

The 1917 Constitution did not significantly address tenant demands, but Article 123 obliged employers to provide affordable, comfortable, and hygienic housing for workers, establishing a national housing fund for credit to acquire property.2121 (Español) Artículo 123.Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, Diario Oficial de la Federación, 5 de febrero de 1917.

The city center, a hub of administration, economic, cultural, and financial activity, saw many residents move to developing colonies, forcibly or voluntarily. This period saw the first printing presses, bookstores, banks, and large department stores. Low-income residents often adapted abandoned wealthy homes into tenements, while Revolutionary turmoil worsened services and living conditions in many neighborhoods.

Post-Revolution, efforts to preserve historic buildings led to the muralism movement, initiated by José Vasconcelos, with artists like Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros creating significant murals.

Post-Revolution social measures saw the State build infrastructure and provide educational, health, and recreational facilities. Architecture distanced from European eclecticism, embracing North American influences in domestic construction and reviving colonial forms. Modern amenities like piped water, electricity, and household appliances became common.

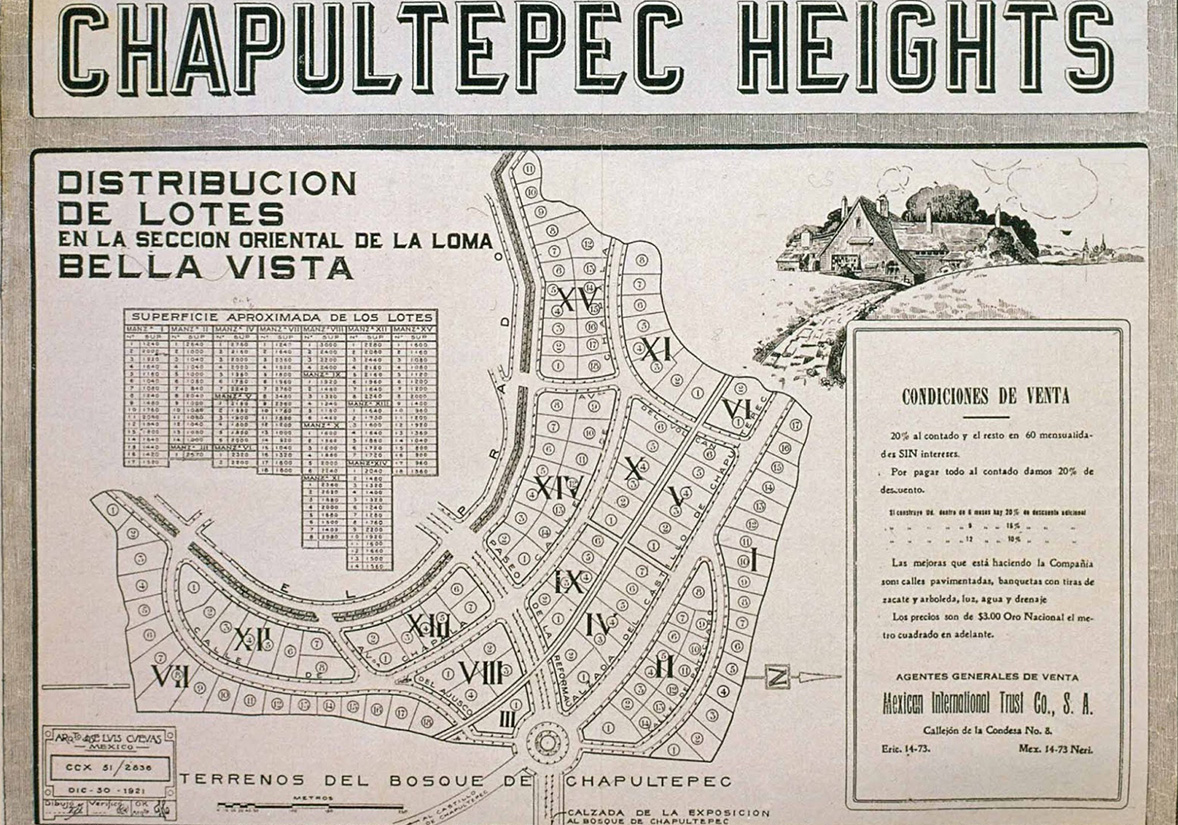

Founded in 1921, the Chapultepec Heights Company developed and subdivided land, constructing roads, creating transportation systems, installing electricity and water plants, manufacturing construction materials, and issuing mortgage bonds.

Its main project, Chapultepec Heights (now Lomas de Chapultepec), was commissioned to architect José Luis Cuevas. For the land acquired by society, located to the west of the city, Cuevas proposed the creation of small self-sufficient cities, limited in size and number of inhabitants, with all public and educational services and vast green spaces.2222 (Español) Sánchez de Carmona Lerdo de Tejada, M. (2009) Las Lomas de Chapultepec de 1921 a 1945. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma Metropolitana: 64.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the city entered a formative phase, with industry serving as the main promoter of modernity, fueling the country’s promising economic growth. As a logic for the growth of the “Federal District,” eleven industrial zones were established, each related to a productive activity, requiring the construction of housing next to them.2323 (Español) Inclan Fuentes, J. (2007). Construcción de ciudad y desarrollo industrial: el caso de la colonia Guadalupe Tepeyac.

Faced with accelerated urbanization, the middle and upper classes began to settle first in the southwestern periphery of the city in the mid-1920s. This movement was aided by new regulations that encouraged the subdivision of lands that had been Porfirian haciendas. Real estate investment and development in these areas offered the potential for rapid profitability, a trend that continued throughout the 1930s.

Promoters of highly densified neighborhoods aimed at less affluent populations, such as La Obrera, often omitted basic urban services like street paving, sanitation, water supply, and public lighting. In the absence of these services, residents of these underdeveloped neighborhoods, including San Pedro de los Pinos and the expansion of Tacubaya, organized efforts to demand government construction of water lines, public lighting, and asphalt paving.

Given the urban infrastructure demands and the real estate boom, cement emerged as an ideal material for the post-revolutionary era due to its industrial suitability. However, its acceptance and popularity were not immediate. In 1923, the Committee to Propagate the Use of Portland Cement was created by various fronts of the cement industry to promote its use. Federico Sánchez Fogarty, an official at the Tolteca cement company, played a crucial role in elevating cement’s status through two publications, “Cemento” and “Tolteca,” released between 1929 and 1932. “Cemento,” with a monthly circulation of 12,000 copies nationwide, allowed both non-specialists and construction professionals to become familiar with cement products and embrace them as cultural symbols.

Carlos Contreras, a Columbia University graduate, was a prominent member of the National Planning Association of the Republic in 1927 and edited the magazine “Planificación” to create a Regional Plan committee for Mexico City and its surroundings, aiming to rationalize urban policy formulation. He described the capital as a “patchwork” city, arguing that its modernization process, like the rest of the country, needed deliberate design. The program titled “The Planning of the Mexican Republic” established guidelines for the new discipline of urban planning and the future of cities.

Regarding transportation and road decongestion, the general strategy involved creating a Coordinated Transportation System for the Federal District, incorporating buses, airports, and their respective terminals. For housing, the Plan advocated the creation of new residential neighborhoods that emphasized the spatial segregation of the city.

In 1925, the Directorate of Civil Pensions was established, a government entity dedicated to addressing the housing problems of State workers through mortgage loans. These loans enabled workers to build modern houses to their liking, choosing from contemporary architectural styles, and selecting their architect, engineer, or master builder, as well as the location within the city. While this approach provided great satisfaction to users, it was ineffective in addressing the broader housing problem, resulting in only a few scattered homes using traditional materials purchased at retail.

The private sector also played a crucial role in urban development. The Compañía Fraccionadora y Constructora de la Condesa decided to divide the land of the former horse racing track of the Jockey Club of Mexico. Following the success of Chapultepec Heights, the company commissioned José Luis Cuevas to design the neighborhood. Cuevas, influenced by the Garden City urban planning school founded by Ebenezer Howard during his studies at Oxford, aimed to improve quality of life through the harmonious synthesis of the countryside and the city.

The layout of Hipódromo Condesa followed this scheme, revolving around a large garden – today Parque México – with an open-air forum and semicircular avenues featuring wide boulevards, medians, and gazebos equipped with fountains, benches, and chandeliers made of concrete and tile. The design respected part of the elliptical shape of the old hippodrome, giving rise to Amsterdam Avenue.

In February 1926, contractors and city council members attended the inauguration of the works. In August of the following year, public lighting was inaugurated with a grand festival featuring fireworks, music, and a flower fight, attended by many residents of the capital. The event concluded with a banquet hosted by the contractors to express their gratitude to the city council for facilitating the construction of the neighborhood.2525 (Español) Editorial Clío. Condesa Hipódromo. México, Editorial Clío, 2008.

Towards the west, De La Lama and Basurto divided part of the land that belonged to the Hacienda de los Morales, located near the recent expansion of Paseo de la Reforma and north of the Bosque de Chapultepec. The Polanco neighborhood became home to upper-middle-class families leaving the rapidly changing city center, as well as residents of older upper-class areas. Polanco also attracted various communities based in the capital, including Jews, Spaniards, Germans, and Lebanese.

By the end of the decade, one of the capital’s first skyscrapers was under construction. Designed by Juan Segura, the Ermita Building was notable for its mixed-use design, featuring shops and a cinema on the ground floor. Comprised of 78 apartments with elevators, laundry service, and security, it attracted a diverse range of tenants, particularly exiled families who temporarily resided in the furnished units. The large investment by the Mier y Pesado family in this building was driven by the potential capital gain of the land.

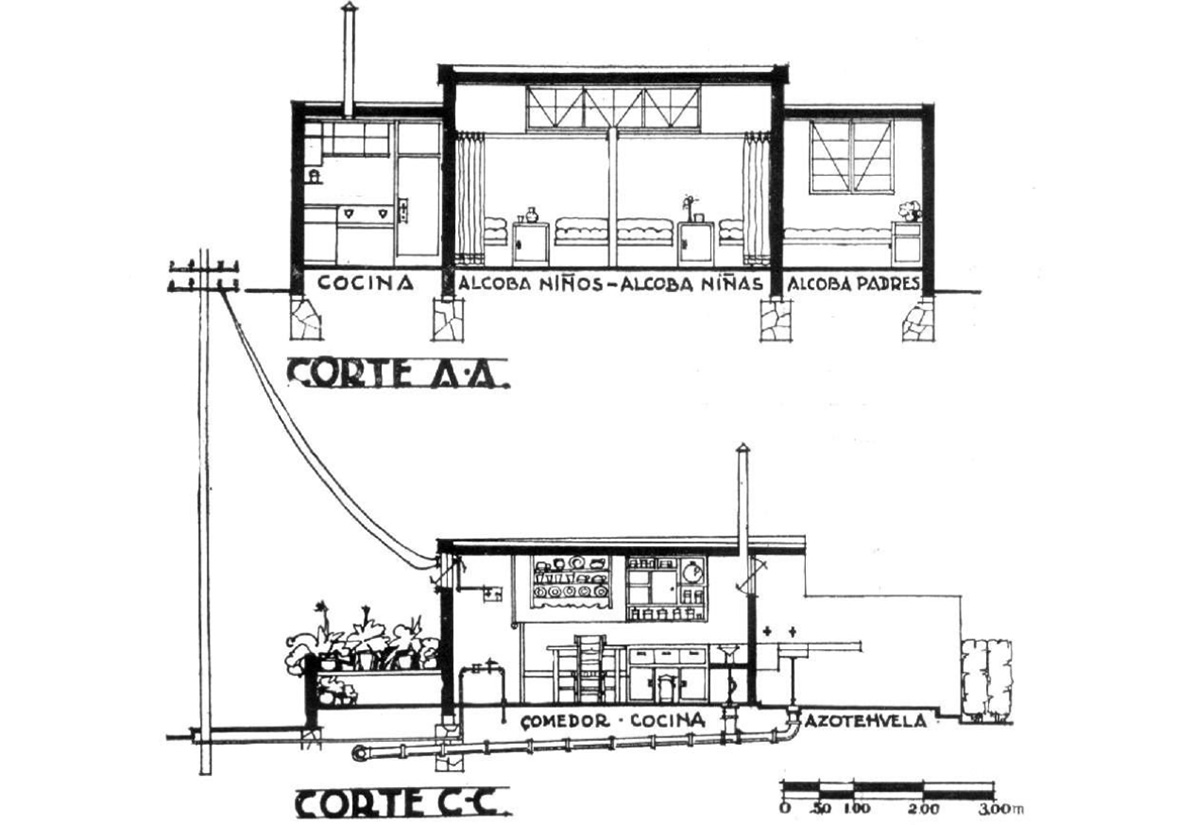

In 1932, architect Carlos Obregón Santacilia, through his company “Modern Construction Sampler,” opened a competition for architects and engineers of the Federal District to design and construct a minimal workers’ house. This low-cost prototype aimed to satisfy the living needs of families in a 54 m² floor plan, improving the housing conditions of the salaried population and enhancing their quality of life.

The contest awarded first place to Juan Legarreta and Justino Fernández, second place to Enrique Yánez, and third place to Augusto Pérez Palacios and Carlos Tarditti. Juan O’Gorman received a mention for presenting a multi-family apartment project instead of a house.

By September 1933, the first housing complexes developed from the winning proposal were completed on the properties of the Balbuena neighborhood. These included 108 homes grouped in four blocks, centered around a garden called the “Jardín Obrero.”2626 (Español) Vázquez Ángeles, J. (2012, marzo). A la caza de Juan Legarreta. Casa del Tiempo, 53, 45-48.

Three types of housing were defined, ranging from 44 to 66 square meters. The smallest units were on one level, while the larger ones were on two levels and included space for a workshop or commercial premises. The interiors were designed with the housewife in mind, featuring a programmatic design for the kitchen-dining room and terrace to control access to the home, along with a multi-use bathroom allowing independent access to the toilet and sink-shower.

Due to the success of the proposal, the government commissioned Legarreta to design 208 houses for workers in the Plutarco Elías Calles neighborhood, on land from the old San Jacinto hacienda. Legarreta incorporated elements from other architects’ proposals in the competition to create a diverse range of solutions.

These complexes partially responded to the need for housing, and by the time Cárdenas took the presidency in 1934, he faced not only the economic crisis of 1929 but also social discontent spurred by the institutionalization of the revolution, which had ended up favoring the economic interests of the highest classes. For Cárdenas, it was essential to invest in social housing for workers affiliated in one way or another to the post-revolutionary state, resulting in the creation of “proletarian colonies.” These colonies were often built on expropriated land and were part of a broader policy favoring the peasant and worker sectors, who during these years “saw an increase in real wages even as the rest of the country struggled against the ravages of the global crisis.”2727 (Español) Davis, D. Urban Leviathan. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 1994: 82.

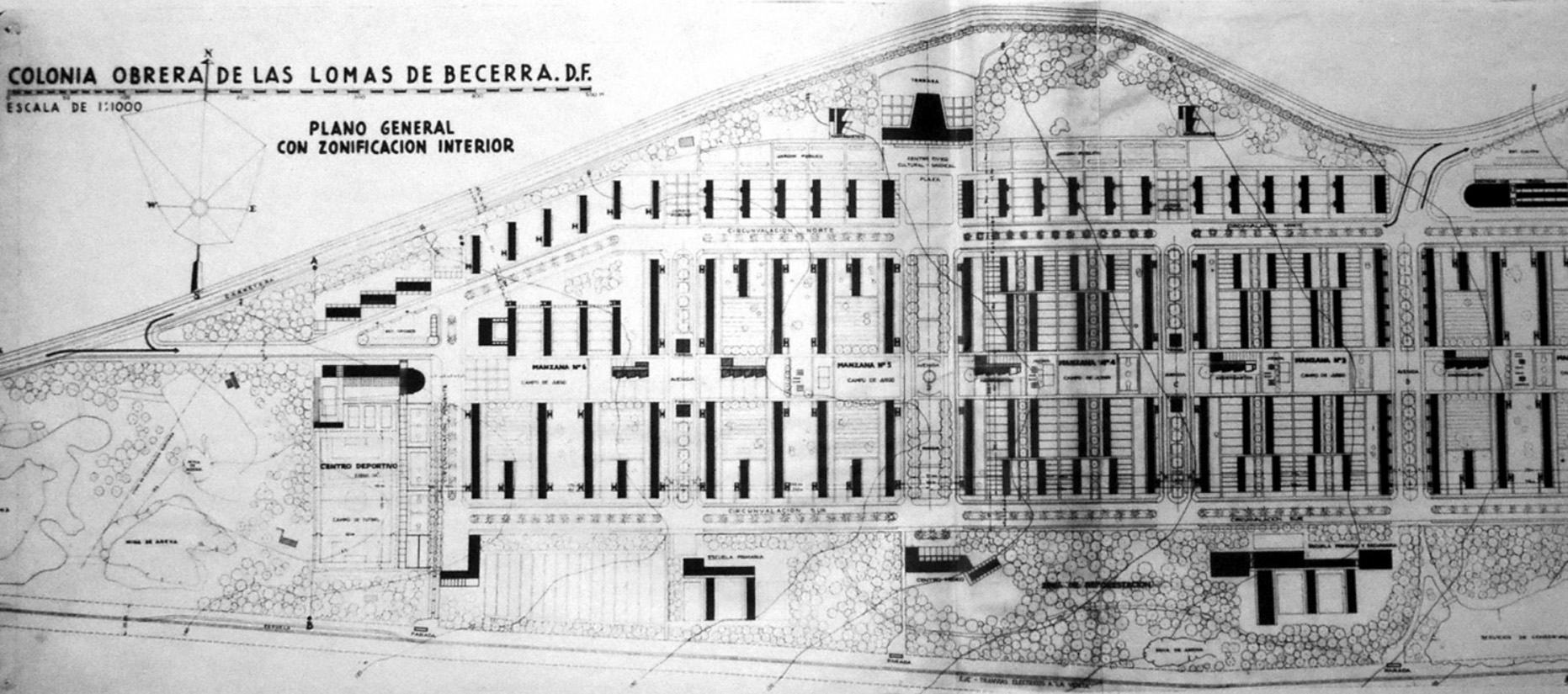

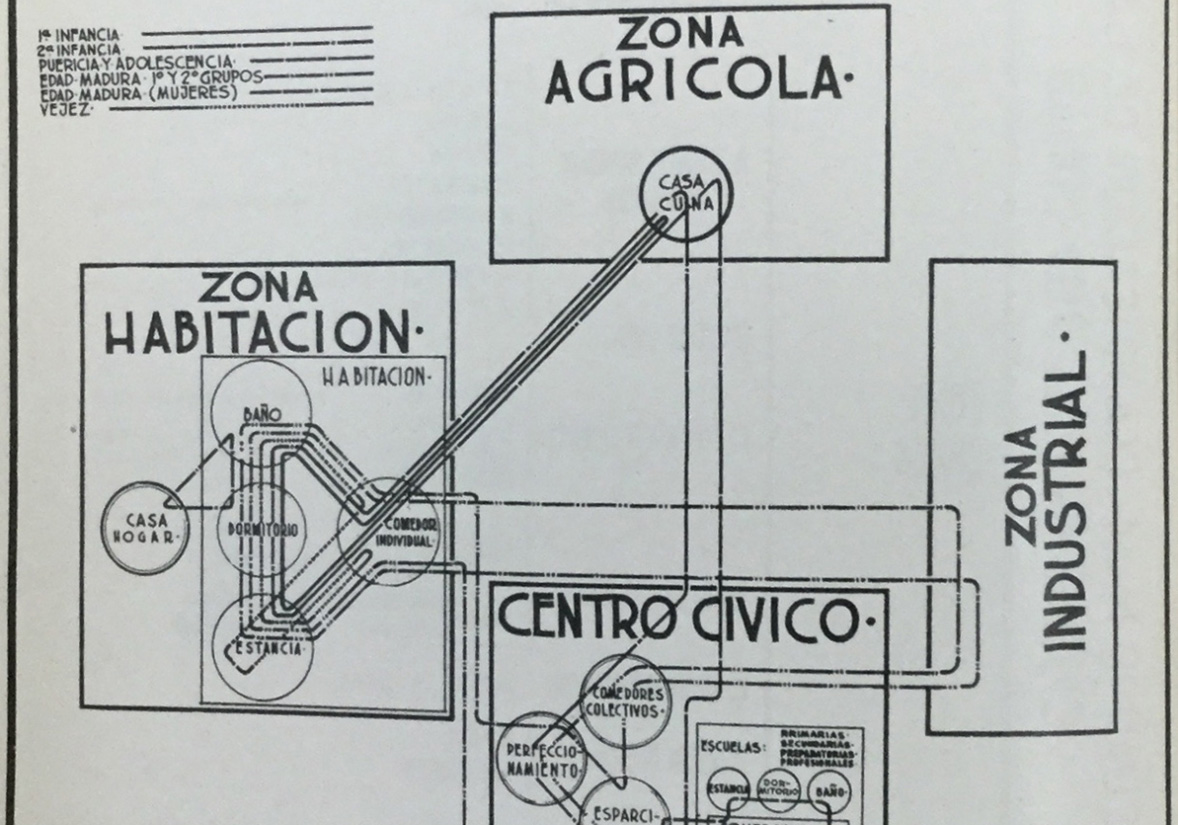

In 1938, the Union of Socialist Architects, led by Alberto T. Arai, planned the ‘Worker’s City’ in the north of the city. Enrique de Anda classified it as a precursor project of the collective housing of Mexican modernity.2828 (Español) De Anda, E. Vivienda colectiva de la modernidad en México: UNAM, 2008. This was envisioned as a proletarian and industrialized city where urban space itself would foster a true post-capitalist collectivity. Four years later, Hannes Meyer designed the master plan for the Colonia Obrera Lomas de Becerra. Although the project was never built, the Presidente Juárez Urban Complex designed by Mario Pani was later constructed on the assigned property.

Another significant project was Ciudad Jardín, composed of two colonies: Xotepingo and El Reloj. These colonies included 1,050 individual 200 m² lots where houses were built from a catalogue offering over 50 options, including rationalist and Californian models. Architect Félix Tena aimed for this colony project to be a model for Mexico and America, proposing large green areas for collective use and streets designed for domestic use, independent of the main circulations.

During the late 1930s, the increasing presence of automobiles in Mexico City emphasized the need for vehicular circulation in urban infrastructure design. This led to the construction of the city’s first vehicular bridge in Nonoalco to extend Insurgentes Norte Avenue towards La Raza and clear the railroad tracks from Buenavista station and the Tlatelolco yards.

The economic crisis caused by global instability from World War II led to the enactment of the Rent Freezing Law of 1942,2929 (Español) Boletín Mexicano de Derecho Comparado, Número 78. which prevented landlords from increasing rents. This caused many property owners to let their properties deteriorate, as they lacked the funds for maintenance and repairs.

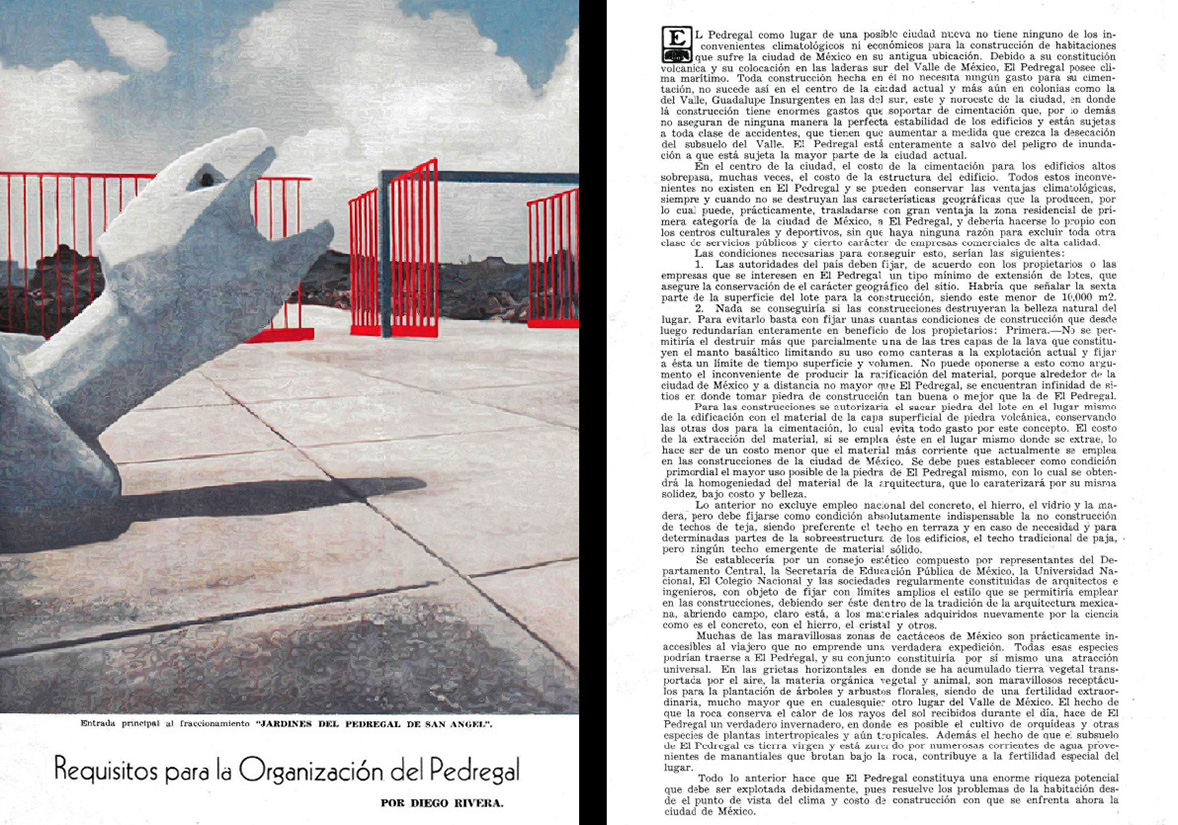

In October 1945, Diego Rivera penned an essay titled ‘Requirements for the organization of El Pedregal’, highlighting its potential as a residential area. He laid out strict conditions to preserve its identity: a minimum square meter for construction, adherence to natural topography for streets, preservation of endemic rock and vegetation, and avoidance of Californian neocolonial architecture. Barragán later advocated these principles, emphasizing minimalist designs in harmony with the environment.

By 1949, urban planner Carlos Contreras, collaborating with Barragán, designed an urban layout for Pedregal guided by lava flow patterns, despite ignoring Rivera’s plea to preserve cacti. An advertising campaign featuring Armando Salas Portugal’s mystical stone landscapes targeted affluent buyers seeking exclusivity.

Despite involvement from modern architects like Francisco Artigas, Manuel Rosen, and Antonio Attolini, many lots in Pedregal deviated from Barragán’s vision, favoring ostentatious styles over serene, green spaces. Barragán expressed dissatisfaction with only 6 of the 50 homes he designed. Decades later, these lands were subdivided into horizontal condominiums.3131 (Español) Eggener, K. Luis Barragan’s Gardens of El Pedregal. Princeton Architectural Press, 2001.

1/

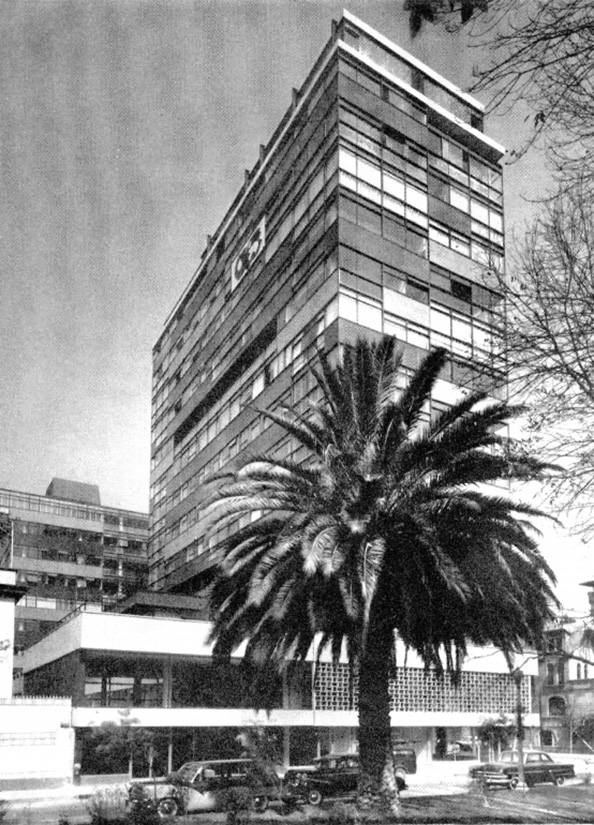

In 1953, Mario Pani championed the Law on Condominiums, founding Condominio S.A. and swiftly selling luxury apartments in the Reforma Condominium before completion. The complex featured two glass prisms with ground-floor shops, mezzanine offices, a 13-floor tower on Paseo de la Reforma, and an eight-story office building on Volga Street, clad in red and beige panels.

Following the success of the Miguel Alemán Urban Center, Pani was commissioned by the General Directorate of Pensions to design the Presidente Juárez Urban Center in Roma. Embodying Le Corbusier’s principles, it replaced the National Stadium, adjacent to the Benito Juárez school within a park, blending neoclassical and neocolonial styles amidst extensive greenery.

The housing complex was home to approximately five thousand residents residing in its 984 apartments. Mario Pani had initially secured certification from expert soil engineers. However, the structural calculations proved inadequate when, 33 years later, the devastating earthquakes of September 19, 1985 struck. The buildings that survived the tremors were promptly demolished, leaving behind only photographic memories.

Five years following the completion of CUPA, Lazo proposed an experimental model of popular housing radically divergent from Pani’s approach. It ingeniously integrated into the landscape, functioning not only as dwellings but also as atomic and anti-aircraft defenses.

The selected quadrant for the Belén Caves, situated in Belén de las Flores along the Toluca highway, featured a steep slope exceeding 30 degrees, which was methodically cut in successive, staggered layers. The complex’s blueprint showcased terraces for circulation and service patios. The front elevation revealed cantilevers where each unit was excavated, forming the façade that illuminated and ventilated the homes while providing access.

Dubbed “cells” by Lazo, these vaulted modules lacked intermediate walls and roofs. Within each 60-square-meter space, a prefabricated service core included the kitchen and bathroom. A room and bedroom accommodated up to four beds with informal partitions.3232 (Español) Bravo Saldaña, Y. Carlos Lazo. Vida y obra. Facultad de Arquitectura, UNAM. The units’ 2-meter-tall glass and metal gate facades starkly contrasted with the complex’s organic surfaces and vernacular character. Residents paid 10,000 pesos at the time, with the original project encompassing comprehensive services, commercial areas, and recreational facilities.

Sadly, Lazo passed away before witnessing the completion of the Belén Caves. According to Dr. María de Lourdes Cruz González Franco in “The Second Modernity,” around 80% of the homes were finished posthumously.3333 (Español) Peraza Guzmán, M. Segunda modernidad urbano arquitectónica. UAM, 2014. Over the years, local residents transformed the site into a thriving community, adding new avenues, sidewalks, and essential services. Regrettably, governmental neglect led to the erosion of the caves’ infrastructure, culminating in a late 1980s landslide. Authorities evacuated residents, filled the cavities, and provided materials and plots for rebuilding homes outside the caves.

Similar to the Belén Caves, other projects expanded towards the city’s outskirts. One such endeavor was commissioned in 1950 by Mario Pani’s Planning and Urbanism Workshop. The Northern Regional Plan of Mexico City aimed to urbanize areas fostering industrial growth, particularly Naucalpan. Pani envisioned creating satellite cities to meet the rising demographic demand, forming a network of orbiting settlements around the capital.

Emphasizing automobile use, the project prioritized high-speed vehicular traffic, adopting a layout resembling the organic structure of a tree. Influenced by urban planner Herman Herrey, the Pani workshop designed circuits and avenues to facilitate continuous circulation without intersections or traffic lights, echoing Herrey’s metaphor of a tree’s trunk, branches, and foliage.3434 (Español) Herrey, H. (abril 1944) Comprehensive Planning for the City: Market and Dwelling Place. Pencil Points. The Magazine of Architecture: 81-90.

Inaugurated in 1957, Ciudad Satélite was promoted in media as “A city outside the city.” Despite its modernity, the project sought to rekindle architecture’s sublime aspirations, aiming to evoke emotions and serve as a communicative expression. It envisioned an idyllic community based on coexistence and mutual understanding.

1/

The genesis of Ciudad Nezahualcóyotl arose amidst Mexico’s rural-urban migration spurred by the industrialization model of import substitution and the deepening scarcity of well-paying jobs since the mid-20th century. In this setting, waves of migrants from the countryside and central Mexico City were drawn by the promise of homeownership in an area initially characterized by dust, mud, and a severe lack of basic urban amenities. The irregular urban layout starkly contrasted with the illegal subdivisions emerging on the dried-up Lake Texcoco.

Over decades, Nezahualcóyotl evolved from a mere dormitory city into a thriving municipality, eventually becoming a pivotal development hub in eastern Mexico City’s Valley. Its socioeconomic influence extended into neighboring municipalities and delegations, a trend underscored by the inauguration of the Jardín Bicentenario commercial park on a former landfill, financed by private sector resources with state and municipal government support.

The Nonoalco-Tlatelolco Urban Complex epitomized a shift in state policy from the 1940s towards ambitious social welfare and transport projects. These initiatives left an indelible mark on Mexico City’s urban landscape, significantly modernizing it amid mixed reactions dubbed by local media as “the big project,” reflecting a blend of astonishment and muted dissent.

Mario Pani’s vision from CUPA promoted a vertical model featuring self-sustaining habitats with extensive infrastructure and urban amenities akin to a standalone city. While addressing housing shortages and traffic congestion, these projects also showcased the state’s largesse during a period of uneven urban transformation and structural fragility in the capital.3535 (Español) Márez Tapia, M. (2010) La unidad habitacional Nonoalco Tlatelolco. Memoria y apropiación del espacio urbano. México: INAH: 54.

Between 1950 and 1970, Mexico’s population more than doubled, underscoring the urgency for effective urban transport solutions. Prior to the inauguration of the Mexico City metro, over half of the city’s trips occurred beyond the central perimeter, spanning Cuauhtémoc, Miguel Hidalgo, Venustiano Carranza, and Benito Juárez. Meanwhile, a significant populace resided in suburban areas poorly served by tram and bus routes. Initial proposals for an underground system surfaced in the 1950s, but the 1957 earthquake instilled skepticism, notably among officials like Regent Ernesto P. Uruchurtu, regarding subterranean urban infrastructure.

In 1968, a delegation of workers traveled to Veracruz to receive the inaugural subway wagons from France. On September 4, 1969, amidst ceremony led by Gustavo Díaz Ordaz and Regent Alfonso Corona del Rosal, the iconic MP-68 train commenced its inaugural journey from Insurgentes station to Zaragoza. By 5:58 am the following day, regular operations began, with an estimated half a million passengers in the first eighteen hours alone.

In May 1971, President Luis Echeverría established the National Tripartite Commission, uniting labor, business, and government sectors to address fundamental national issues. Proposals included pooling employer contributions into a national fund to facilitate housing loans for workers, leading to the promulgation of the INFONAVIT law in April 1972 and the subsequent establishment of the institute bearing the same name.3636 (Español) Vivienda y vida urbana en la Ciudad de México: la acción del Infonavit. (n.d.). El Colegio de México.

In 1972, construction commenced on the inaugural housing complex of INFONAVIT in Iztacalco, an ambitious project spanning 226 hectares with the capacity to accommodate up to 120,000 residents. This development marked a milestone in scale and scope, featuring a comprehensive array of amenities: sports facilities, four lakes, expansive green spaces, shopping areas, schools, social centers, an urban civic center, a gas station, a social security hospital, and a cemetery. The housing distribution comprised 42% apartments in five-story multifamily buildings, 38% triplex houses, and 20% single-family residences, all designed with integrated play areas, shops, and plazas.

El Rosario, the first group inaugurated under INFONAVIT, was graced by the presence of President Luis Echeverría. It included 5,000 housing units along with educational facilities, commercial outlets, and recreational and ornamental features. The residences were structured across buildings ranging from two to twelve floors, encompassing single-family homes, duplexes, and multi-family units. Each resident enjoyed approximately 10m2 of living space, while the design emphasized neighborhood cohesion by creating communal squares around the buildings to blend harmoniously with the surrounding urban environment.

Additionally, the INFONAVIT cultural board launched a program aimed at fostering cooperation between artists and residents. This initiative was conceived to cultivate a sense of community spirit and collaborative effort among the inhabitants, nurturing their creative and manual skills.

By the early 1970s, the National Housing Institute underwent transformation into the National Institute for Community Development (INDECO). This restructuring was part of the state’s strategy to aggressively tackle the country’s housing deficit, expanding coverage comprehensively and catering to specific demographic needs. This period saw the establishment of major worker-centric funds: INFONAVIT, FOVISSSTE, and FOVIMI.

The 1979 National Housing Program was pivotal in broadening social coverage and prioritizing the housing requirements of low-income segments. It laid the groundwork for coordinated efforts across different levels of government and collaboration with social and private sectors. The program underscored the societal responsibility, under state leadership, to address national housing needs. Key strategies included equitable distribution of housing initiatives nationwide, increased public sector involvement in direct housing production, regulation of construction materials, and promotion of suitable technologies.

In the early 1980s, INDECO was dissolved, paving the way for state housing institutes. These institutions would later become critical tools for decentralizing Mexico’s housing activities during the 1990s.

The seismic upheaval that struck Mexico City at 7:19 a.m. on September 19, 1985 originated 400 kilometers away in the Pacific Ocean’s subsoil near the mouth of the Balsas River, known as the Michoacán Gap, measuring 8.1 on the Richter scale. The earthquake’s epicenter caused widespread devastation, particularly affecting neighborhoods like Roma, Cuauhtémoc, Tránsito, Obrera, and others. Notably, the Nonoalco-Tlatelolco and Juárez Multifamiliar Units suffered significant damage.

Infrastructure citywide sustained severe impairment across its water supply, electrical grid, lighting networks, telecommunications, and drainage systems. The human toll was staggering: approximately 4,500 fatalities and over 14,000 injuries. Beyond the human losses and destruction, the 1985 earthquake stands as Mexico City’s most catastrophic disaster due to its unprecedented scale, toppling thousands of homes, including historic mansions and vulnerable neighborhoods. The earthquake left 412 buildings completely demolished and 5,728 structures severely or moderately damaged.

In the aftermath of the devastating 1985 earthquakes in Mexico City, residents of the affected neighborhoods found themselves on the streets, tending to what remained of their homes and belongings. Initially, basic services like gas, water, and electricity were unavailable, and governmental aid did not reach the hardest-hit areas promptly. However, community-driven efforts emerged as crucial lifelines, with local residents, supported by volunteer brigades from universities like UNAM, UAM, and the Polytechnic, providing essential supplies and assistance to those in critical need.

Amidst the chaos, property owners in neighborhoods such as Cuauhtémoc drafted declarations stating their homes were uninhabitable and advocated for demolition. Meanwhile, tenants, bolstered by the brigades, submitted assessments outlining the perilous conditions of their properties and proposing urgent repair measures to make them safe for reoccupation where possible.

In neighborhoods like Guerrero and Tránsito, some property owners took matters into their own hands, dispatching teams to demolish structurally compromised buildings. Authorities, on the other hand, cut off utilities in an attempt to disperse residents camping on the streets, reinforcing their stance of providing assistance only to those centralized in official shelters. In the city center, military presence was employed to deter residents from occupying public spaces.

One of the most severely affected housing complexes was the López Mateos Urban Complex, where the Nuevo León Building was completely destroyed. President Miguel de la Madrid engaged with displaced tenants, promising reconstruction and accountability for the buildings’ inadequate structural integrity. However, progress on rebuilding efforts was slow, prompting public outcry and eventual government negotiations to provide insurance, compensation for losses, and soft loans to former residents seeking new housing.

In Tlatelolco and other complexes, survivors organized protests against forced sales and inadequate governmental responses. Their defiance was evident in signs declaring “Not for sale” across buildings, reflecting widespread discontent among earthquake victims. These demonstrations culminated in citywide marches, uniting affected communities from Morelos, Guerrero, Centro, Santa María La Ribera, and Tepito neighborhoods.

Responding to the crisis, the Popular Housing Renewal Program was established to revitalize central urban spaces. This initiative enabled over 40,000 families living in deteriorated conditions to become homeowners, preserving their neighborhoods and way of life. By May 1986, the Democratic Concertation Agreement for the Reconstruction of Housing under the program outlined the terms for new constructions, renovations, and minor repairs, benefiting nearly 250,000 people within 18 months of the earthquakes.

The neighborhoods selected for the program were among the oldest in the city, characterized by aging infrastructure and frozen rent controls, which limited residential mobility. A significant portion of the program’s beneficiaries had lived in these areas for decades, underscoring deep community ties and highlighting challenges posed by deteriorating housing stock and economic constraints.

As the government allocated substantial funds—initially estimated at 60 to 70 billion pesos—for housing reconstruction, subsequent budget items for 1986 indicated a revised allocation of 23 billion pesos, reflecting ongoing efforts to address the aftermath of the disaster through comprehensive urban renewal and social welfare programs.39

During the 1990s, public sector involvement in housing provision decreased significantly to only 40%. This meant that more than 50% of lower-income families lacked access to adequate housing solutions. This trend worsened following financial deregulation, which removed legal reserve requirements from private banks, and changes to the INFONAVIT Law, which redirected housing policy.4040 (Español) García Peralta, B. (2010). Vivienda social en México (1940-1999): actores públicos, económicos y sociales. Cuadernos de vivienda y urbanismo. Vol. 3, No. 5, 2010, pp. 34 – 49.

Casas Geo, established in 1973, played a pivotal role during this period as a developer specializing in affordable housing across Mexico and Latin America. It became a key contractor for INFONAVIT and FOVISSTE, and in 1994, it was listed on the Mexican Stock Exchange (BMV), joining the Price and Quotation Index. Casas Geo managed the entire housing development process—from land acquisition and design to construction, marketing, and delivery. Over the years, the company provided nearly 655,000 homes in Mexico, accommodating over 2.4 million people. However, it later faced criticism for its business practices, and by 2013, its shares were suspended from trading.

The government’s strategy during this period prioritized the financial sector and housing developers associated with it, while also opening the market to foreign investment. This shift did not imply that the previous model was superior; rather, it funneled substantial financial resources—often with minimal oversight—into a sector that demonstrated inefficiencies and lacked adequate regulation for sound management. State intervention in housing was limited, with insufficient fiscal investment, and there was no robust capitalist real estate sector capable of meeting the housing needs even of financially capable buyers.

- 1 (Español) Sánchez Martínez, M. La Ciudad de México en la cartografía oficial del Porfiriato: Los planos oficiales de la Ciudad de México de 1891 y 1900. Universidad Nacional Autónoma Metropolitana: 2016: 5.

- 2 (Español) Real Academia Española. (2001). Diccionario de la lengua española (22.a ed.). Consultado en http://www.rae.es/rae.html

- 3 (Español) Más adelante, el ayuntamiento cambiaría el nombre oficial de ésta a colonia Nuevo México debido al estallido de la Guerra de los Pasteles y a un impulso nacionalista del Estado.

- 4 (Español) En particular las Leyes de desamortización —Ley Lerdo del 25 de junio de 1856— y nacionalización de bienes eclesiásticos —promulgada el 12 de julio de 1859.

- 5 (Español) Anda, E. (2013). Historia de la arquitectura mexicana (p. 193). Barcelona: Gustavo Gili: 193.

- 6 (Español) Se adaptaban entre otros programas para ser escuelas, hospitales y vivienda.

- 7 (Español) Alba González, M. (2015). Vejez, memoria y ciudad. Editorial Miguel Ángel Porrúa.

- 8 (Español) Reyes Fragoso, A. (agosto 2006). "Santa María la Ribera, colonia centenaria". El Universal.

- 9 (Español) De Gortari Rabiela, R., Hernández Franyuti, R. (1998) La Ciudad de México y el Distrito Federal: Una historia compartida. México: Instituto de Investigaciones Hisóricas José María Mora: 1998:

- 10 (Español) Anda, E. (2013). Historia de la arquitectura mexicana (p. 193). Barcelona: Gustavo Gili: 196.

- 11 (Español) Ribera Carbó, E. (2003). Casa, habitación y espacio urbano en México. Revista electrónica de geografía y ciencias sociales, Vol. VII, núm. 146(015). Disponible en: http://www.ub.edu/geocrit/sn/sn-146(015).htm

- 12 (Español) Martinez Dominguez, Margarita G. (2011) La colonia de los Arquitectos a través del tiempo. México: Casa Juan Pablos.

- 13 (Español) Pardo, F. (junio 2013). Vivienda y tabaco. México: Arquine. https://www.arquine.com/vivienda-y-tabaco/

- 14 (Español) Almandoz Marte, A. (2002) Planning Latin America's Capital Cities 1850-1950. Reino Unido: Routledge: 167.

- 15 (Español) Ibid.

- 16 (Español) García Fernández, R. (2018) La colonia Escandón. Políticas urbanas y transformación socioespacial. Boletín De Monumentos Históricos, (38), 115-137.

- 17 (Español) Revistavector.com.mx. (2019) Espacio de todos; las vecindades en la ciudad de México – Plataforma Vector.

- 18 (Español) González Gamio A. (2019). La Jornada: Colonia con historia. [online] La Jornada.

- 19 (Español) Montes de Oca, P. (2015). Vida y milagros de… la colonia Roma. México: Algarabía.

- 20 (Español) Cohen, M. y Cohen, M. (1979). Política y vivienda en México 1910-1952. Revista Mexicana de Sociología, 41(3), p.769

- 21 (Español) Artículo 123.Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, Diario Oficial de la Federación, 5 de febrero de 1917.

- 22 (Español) Sánchez de Carmona Lerdo de Tejada, M. (2009) Las Lomas de Chapultepec de 1921 a 1945. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma Metropolitana: 64.

- 23 (Español) Inclan Fuentes, J. (2007). Construcción de ciudad y desarrollo industrial: el caso de la colonia Guadalupe Tepeyac.

- 24 (Español) Sánchez Ruiz, G., López Rangel, R., Ayala Alonso, E. (2003) Planificación y Urbanismo visionarios de Carlos Contreras. Escritos de 1925 a 1938. México: UNAM, UAM-A y Universidad de San Luis Potosí.

- 25 (Español) Editorial Clío. Condesa Hipódromo. México, Editorial Clío, 2008.

- 26 (Español) Vázquez Ángeles, J. (2012, marzo). A la caza de Juan Legarreta. Casa del Tiempo, 53, 45-48.

- 27 (Español) Davis, D. Urban Leviathan. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 1994: 82.

- 28 (Español) De Anda, E. Vivienda colectiva de la modernidad en México: UNAM, 2008.

- 29 (Español) Boletín Mexicano de Derecho Comparado, Número 78.

- 30 (Español) Kochen, Juan José. n.d. El Primer Multifamiliar Moderno.

- 31 (Español) Eggener, K. Luis Barragan's Gardens of El Pedregal. Princeton Architectural Press, 2001.

- 32 (Español) Bravo Saldaña, Y. Carlos Lazo. Vida y obra. Facultad de Arquitectura, UNAM.

- 33 (Español) Peraza Guzmán, M. Segunda modernidad urbano arquitectónica. UAM, 2014.

- 34 (Español) Herrey, H. (abril 1944) Comprehensive Planning for the City: Market and Dwelling Place. Pencil Points. The Magazine of Architecture: 81-90.

- 35 (Español) Márez Tapia, M. (2010) La unidad habitacional Nonoalco Tlatelolco. Memoria y apropiación del espacio urbano. México: INAH: 54.

- 36 (Español) Vivienda y vida urbana en la Ciudad de México: la acción del Infonavit. (n.d.). El Colegio de México.

- 37 (Español) López Monjardin, A. y Verduzco Ríos, C. (enero – marzo 1986) Vivienda popular y Reconstrucción, Cuadernos políticos, número 45, México D.F.: 25-37.

- 38 (Español) Esquivel Hernández, M. (2016). El Programa de Renovación Habitacional Popular: Habitabilidad y permanencia en áreas centrales de la Ciudad de México. Iztapalapa. Revista de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, (80), pp.69-99.

- 39 (Español) López Monjardin, A. y Verduzco Ríos, C. (enero – marzo 1986) Vivienda popular y Reconstrucción, Cuadernos políticos, número 45, México D.F.: 25-37.

- 40 (Español) García Peralta, B. (2010). Vivienda social en México (1940-1999): actores públicos, económicos y sociales. Cuadernos de vivienda y urbanismo. Vol. 3, No. 5, 2010, pp. 34 - 49.

Housing in Mexico City

* Investigación

¤ Proyecto particular

∞ julio 2020