Over the past century, the consumer landscape has undergone significant transformations, compelling commercial establishments across all categories to continuously rethink their spatial organization. In more recent decades, various forms of architecture have emerged to meet the expectations of a public deeply immersed in global consumer culture. Consequently, this audience has become increasingly attuned to the symbolic meanings associated not only with the products they purchase, but also with the spaces where their consumption experience unfolds, fostering a sense of identification with a particular lifestyle.

The introduction of department stores in Mexico at the end of the 19th century marked a milestone in the concentration of commercial products and the circulation of merchandise in the country. During the reign of Maximilian of Habsburg, European immigrants arrived with a keen interest in expanding their wealth through large-scale investments. Leveraging the opening to new forms of commercial exchange at the time, a group from Barcelonette, a migrant town in the French Alps, seized the opportunity to establish The Mercantile Center. The department store was inaugurated on September 2, 1889, in the presence of President Porfirio Díaz, in an event of considerable media significance. A contemporary chronicle vividly describes the occasion: “The most distinguished and respectable families of good society convened at the venue, and by 5:30 in the afternoon, a throng of people had flooded into all the departments that comprised the expansive commercial establishment.”11 Lozada León, Guadalupe. “¿Cuál Fue La Primera Tienda Departamental En México?”. 2021. Relatos E Historias En México. https://relatosehistorias.mx/nuestras-historias/cual-fue-la-primera-tienda-departamental-en-mexico.

This warehouse offered customers a diverse array of products and provided professionals with the opportunity to rent spaces to offer their services. The architectural design of the building played a crucial role in conveying the idea of luxury and status associated with the Great Mercantile Center. Engineered by Daniel Garza and Gonzalo Garita, the complex adhered to the eclectic tradition characteristic of the time. It featured a neo-Greek facade adorned with both fluted and smooth columns, complemented by a series of bronze and zinc sculptures supporting projecting cornices on each level. Additionally, its spacious central hall was adorned with French ornaments and equipped with an iron cage elevator. Crowning the hall was a large stained glass window on the ceiling, attributed to Jacques Gruber of the Nancy School.

Two years later, a nearby building constructed of iron, steel, and carved stone emerged, inspired by European styles and reminiscent of the Bon Marché in Paris. Founded by J. Tron y Cía, a consortium also from Barcelonette, El Palacio de Hierro offered international merchandise displayed in luxurious and captivating showcases.

The Mercantile Center ceased operations in 1966. Following its abandonment, it was restored and transformed into what is now known as the Gran Hotel de la Ciudad de México, located on 16 de Septiembre Street. By this time, consumer preferences had already shifted significantly; individuals sought more than mere acquisition of goods—they desired immersive commercial spaces conducive to socialization and leisure. Consequently, the Mercantile Center became obsolete as producers adapted to the evolving tastes of their clientele in an era where consumption became increasingly aesthetic rather than purely functional.22 Lash, Scott, and John Urry. 1998. Economías De Signos Y Espacios. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu Editores. In the 1950s, a property emerged in Minnesota, United States, that consolidated various commercial establishments alongside leisure and entertainment activities. Operating under this model, it was hailed as the first modern shopping center.33 Gasca-Zamora, José. 2017. “Centros Comerciales De La Ciudad De México: El Ascenso De Los Negocios Inmobiliarios Orientados Al Consumo”. EURE (Santiago) 43 (130): 73-96. doi:10.4067/s0250-71612017000300073.

1/

At that time, Mexican architecture was grappling with abstractionism influenced by international trends. Ludwig Mies Van der Rohe’s “Less is more” doctrine had governed the design of numerous buildings, and the principles of the modern movement had been fully assimilated into the built environment of major cities. Constructions such as the Reforma Condominium by Mario Pani, the building at Río Tigris 133 by Ricardo de Robina and Jaime Ortiz Monasterio, the building at Mérida 5 by Augusto H. Álvarez, and the commercial and office building in Nice and London by Juan Sordo Madaleno and Jaime Ortiz Monasterio, featured glazed volumes supported by grids of industrial materials that showcased the functional and aesthetic qualities of glass.

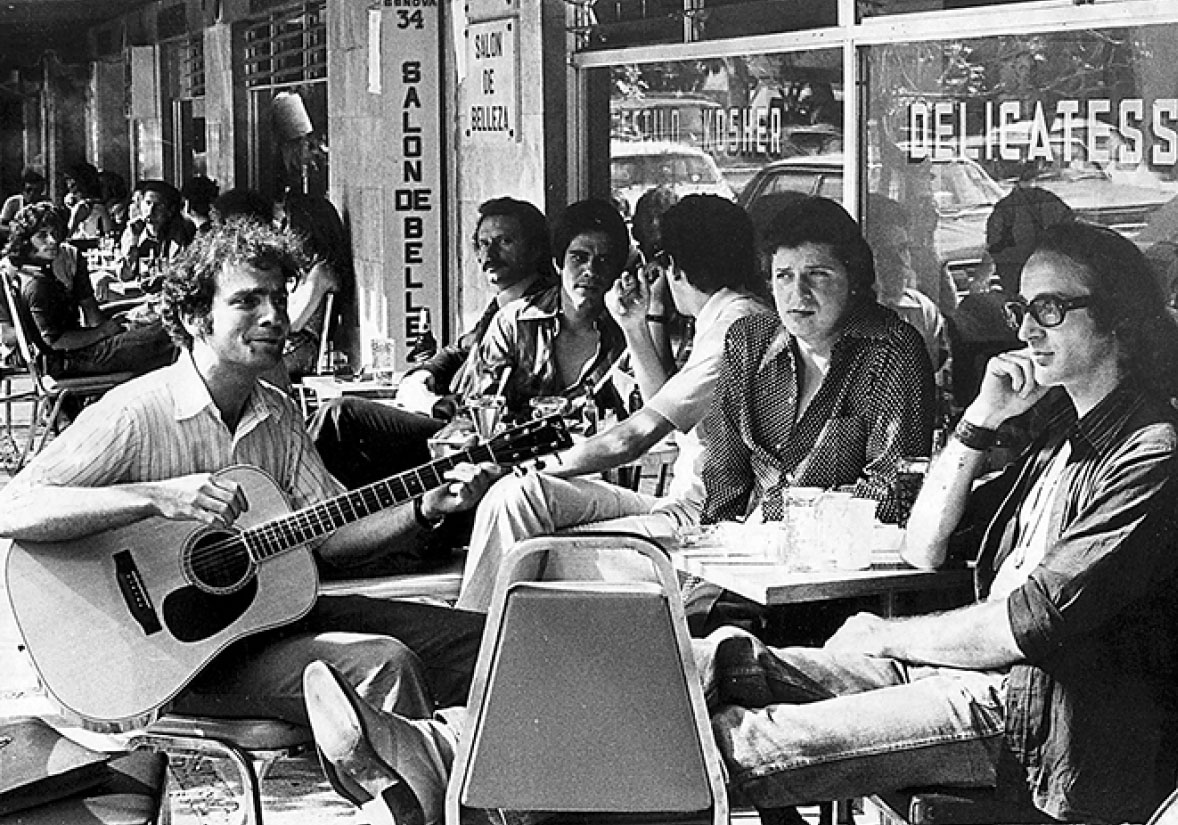

Two architects who embraced this approach were Ramón Torres and Héctor Velázquez.44 Héctor Velázquez Moreno (1922 – 2006) and Ramón Torres Martínez (1924 – 2008) formed Torres y Velázquez Arquitectos y Asociados in 1954, working in partnership for over four decades. Despite their prolific careers, avant-garde proposals, and recognition by important academics such as Louise Noelle, this duo has not received the same level of attention as other architects of their time. It could be argued that there is a historiographic debt owed to them. Motivated by the innovation of shopping centers emerging in other parts of the world, these architects embarked on a search for an ideal location for such a property—a polygon that would cater to a local population with high purchasing power while also attracting consumers from beyond its borders. The Zona Rosa,55 There are several theories about the origin of the neighborhood’s name. One of the most popular suggests that Mexican painter José Luis Cuevas described it as such because it appeared red at night and white during the day. Alternatively, it is mentioned that the artist Vicente Leñero named it this way because it was “too timid to be red and too bold to be white.” Other sources maintain that the name comes from Carlos Fuentes’ “The Death of Artemio Cruz,” where the author mentions that the buildings in the neighborhood were painted pink. Finally, there are versions that suggest the name was a way to soften the term “red-light district” with which it was initially known. situated in the Juárez neighborhood near the Historic Center of Mexico City within the Cuauhtémoc delegation, emerged as a prime candidate. This cosmopolitan district boasted nearly three million inhabitants66 Strukelj, Pedro. “Fachada y variación formal. Análisis de la obra de Ramón Torres y Héctor Velázquez”. Bitácora, no. 14, 2005, p. 60. and enjoyed widespread public attention as a fashionable destination at the time. Frequented by curious tourists, as well as artists and intellectuals donning striking attire that defied social conventions, the Zona Rosa was described vividly by the playwright, essayist, and poet José Joaquín Blanco:

“It was one of the few places where one could stroll freely, without fear of repercussion, dressed as a hippie, or sporting an ultra-miniskirt and hot pants, or flaunting sleek Beatle-style hair and tight, waist-hugging pants that accentuated one’s curves and contours, all in vibrant and extravagant colors. In other parts of the city, such attire often resulted in insults, assaults, and even police arrests.”77 Blanco, José Joaquín. 2005. Postales Trucadas. México, D.F.: Nexos Sociedad Ciencia y Literatura.

This influx was due to an intense commercial activity that occurred among its designer clothing boutiques, antique stores, hotels, outdoor cafes, bars, restaurants and nightclubs.

1/

Agustín Barrios Gómez, a social columnist for the newspaper Novedades, eloquently depicted the vibrant atmosphere of the Zona Rosa in his column “Salada Popoff,” describing it as a melting pot where locals and outsiders, hippies and gentlemen, girls with flowing locks and eccentric attire mingled with elegant ladies adorned in jewelry and luxurious dresses.8 8 Villasana, Carlos, and Ruth Gómez. “Antes de que hubiera centros comerciales”. El Universal, September 2, 2017.Men sporting bowler hats or straw hats rubbed shoulders with a diverse crowd traversing the streets. Some experts suggest that due to its bohemian ambiance and cultural vibrancy, the neighborhood aspired to emulate what the Village was to New York, the Via Veneto to Rome, and the Rive Gauche to Paris.99 Campos, Marco Antonio. “La Zona Rosa En Los Años Cincuenta Y Sesenta – Detalle De Estéticas Y Grupos – Enciclopedia De La Literatura En México – FLM – CONACULTA”. 2018. http://www.elem.mx/estgrp/1329.

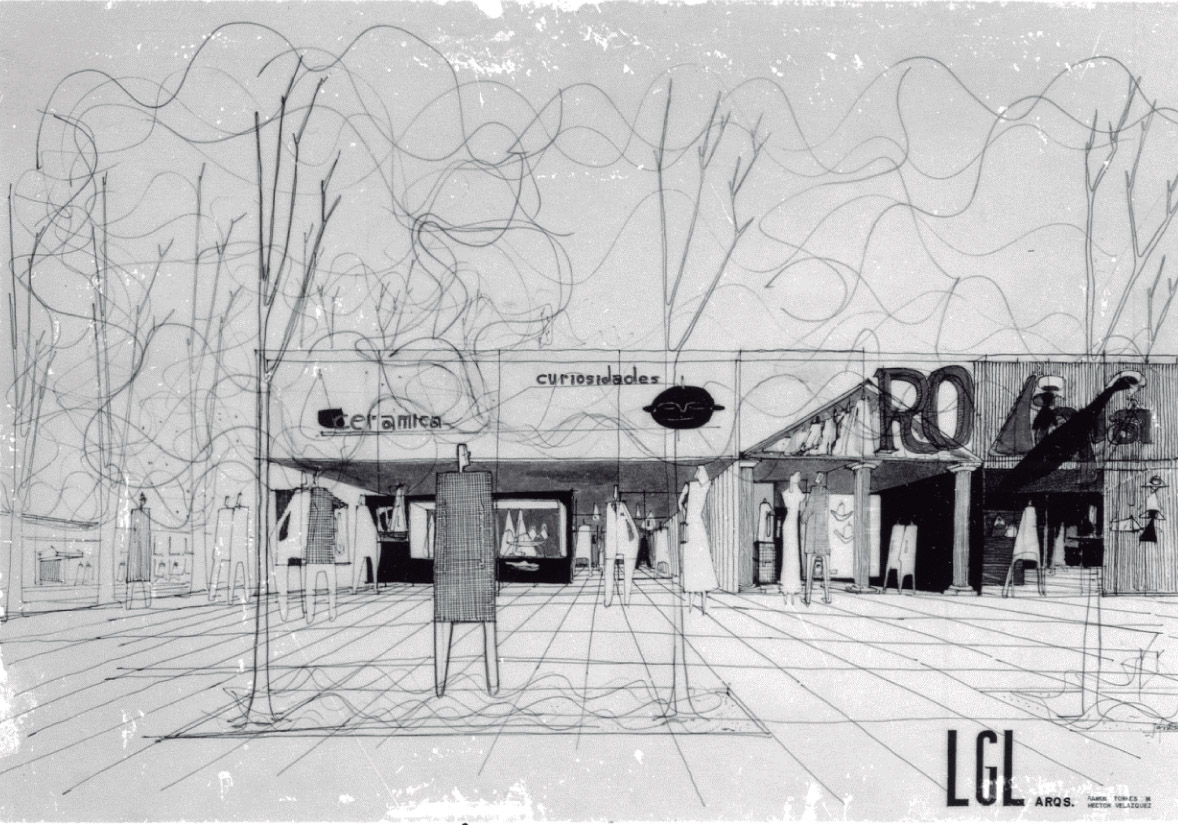

Owing to its intense commercial activity, centralized location, and undeniable charm, the region proved highly lucrative for a large-scale commercial project. In the 1950s, Ramón Torres and Héctor Velázquez identified four contiguous lots within a block southeast of the Zona Rosa, adjacent to the streets of London, Génova, and Liverpool. These lots, situated near the intersection of Reforma and Insurgentes avenues—envisioned by architect Mario Pani as the city’s epicenter—caught their attention.1010 Graciela de Garay Arellano. 2000. Historia Oral De La Ciudad De México. México, D.F.: CONACULTA. Despite their potential, the architects noted that each lot was individually unprofitable due to their “uncommercial” proportions: narrow and excessively deep.1111 Noelle, Louise. “Retrospectiva de la Obra de Ramón Torres” Arquitectura México, no. 117, 1978, p. 21. FFaced with this challenge, Torres and Velázquez proposed to the owners to merge the plots while preserving their respective ownership rights, creating a commercial center that would span the entire area.1212 Ibid.

Following extensive studies on land value, area profitability, current construction regulations, and a profound understanding of both functionalist construction systems and modern architectural language, the architects developed the architectural project for the Plaza Jacaranda Shopping Center, later known simply as Pasaje Jacaranda. Completed in 1959, the complex marked the inception of this typology in the country’s urban fabric, presenting a building that was undeniably sui generis. Comprising a concrete structure at its core, the one-level complex covered an area of approximately 4,000 m2 and featured a dynamic system of outdoor routes and spaces distributed across different levels.

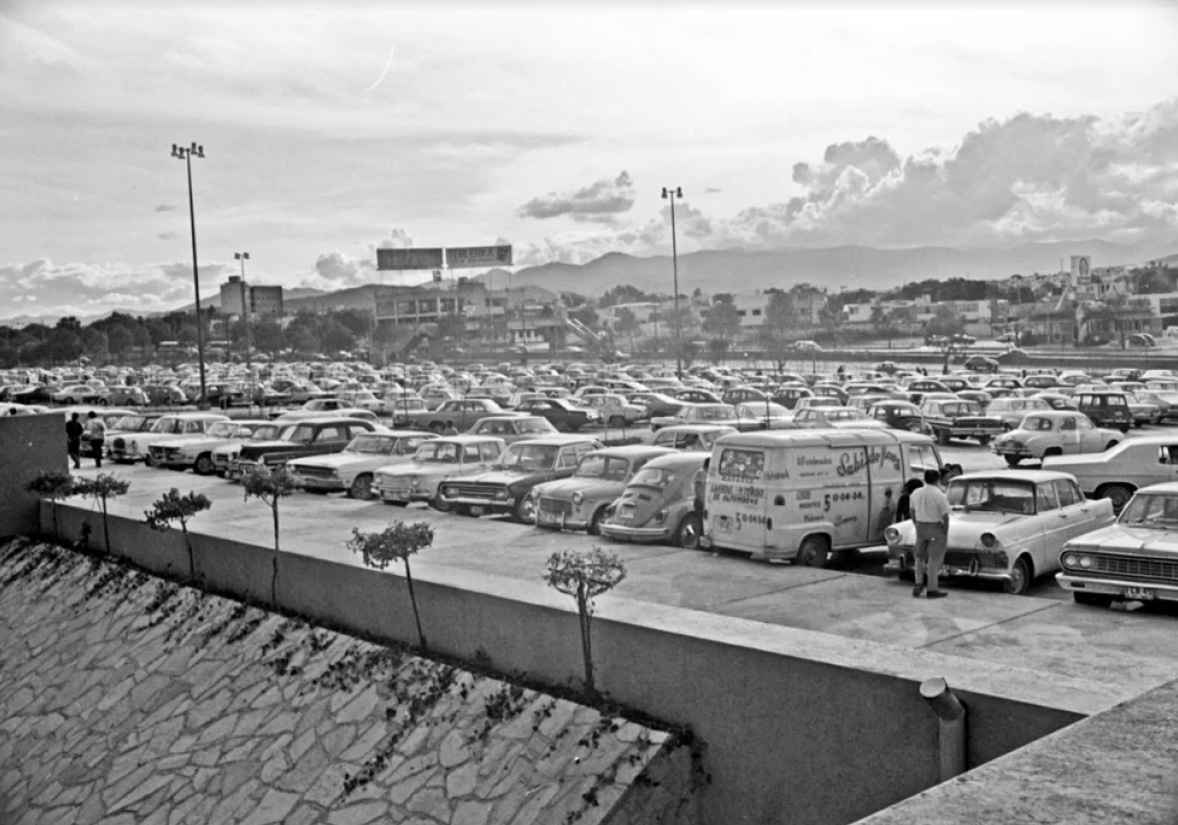

In a bid to integrate the commercial passage with the immediate landscape, Torres and Velázquez liberated the fronts of the buildings, incorporating them into the pedestrian routes. To achieve this permeability, the project included a parking lot on the roofs of the buildings, ensuring that cars never obstructed access to the shops and enabling free movement through the square from one perimeter street to another. Thus, pedestrians became the focal point of the project, while cars remained out of sight—a departure from the prevailing trend where automobiles held significant prominence in contemporary buildings.

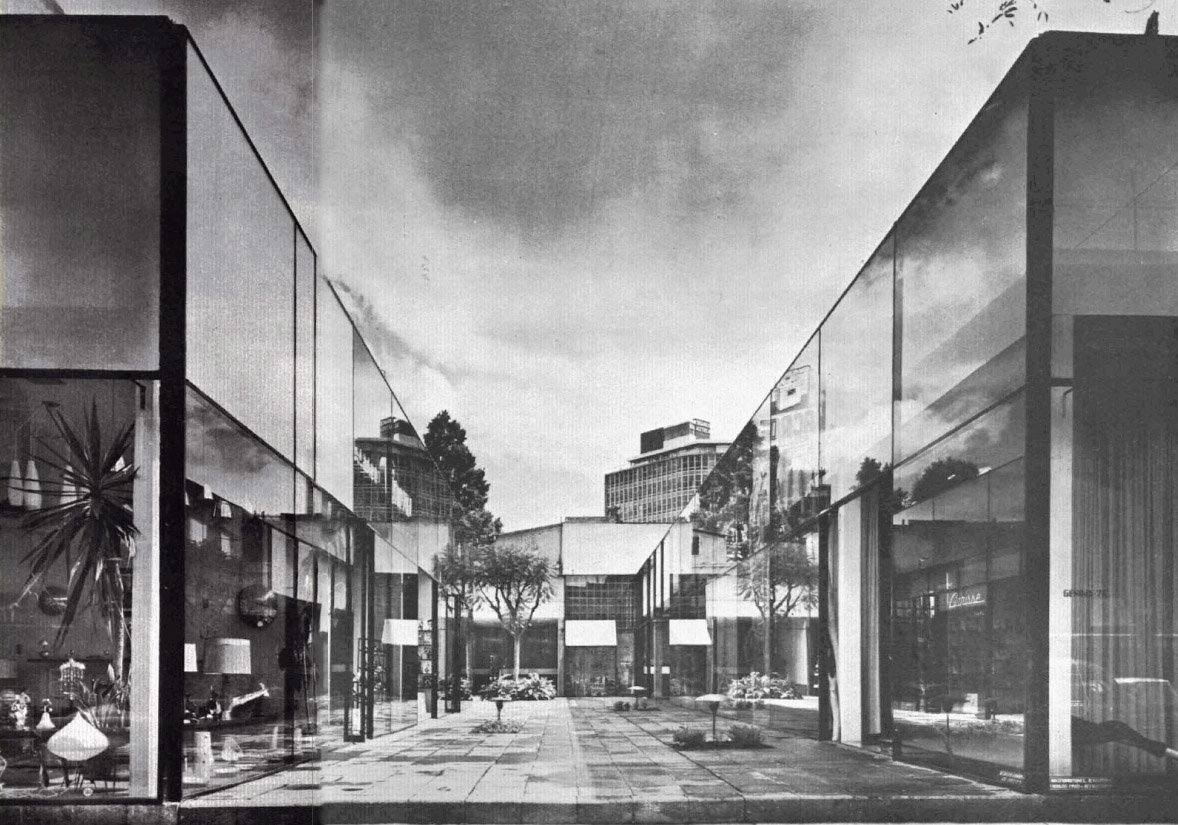

The feeling of openness was heightened at a structural level by the transparency of the buildings, a departure from earlier department stores where commercial activity was contained within the building, disconnected from the outside environment. Drawing inspiration from the designs of Mies Van de Rohe, such as the Farnsworth House or Crown Hall, which fostered a seamless integration with the exterior through glass facades and open internal spaces, the architecture of the Pasaje Jacaranda exposed its interiors to pedestrian traffic and the surrounding urban landscape.

This architectural solution was realized using exceptionally large custom-made glass panels, divided by horizontal crossbars coinciding with the upper part of the entrances to the premises.1313 Gastón Guirao, Cristina. “Sobre la pista de los fotógrafos de arquitectura en América Latina”. En: Alcolea, R.A, Tárrago-Mingo, J., eds., en el Congreso internacional: Inter photo arch “”Interacciones “”, Pamplona, November 2-4, 2016. These panels were further displaced towards the exterior, enhancing the continuity of the glass panels and the perception of depth towards the interiors. Through these expansive windows, the interiors of the premises were fully visible, unless owners chose to use curtains or objects to obstruct the view. The architects’ intent was to transform the glass into a canvas for the interiors of the premises,1414 s/a. “Pasaje Jacarada”. Arquitectura México, no. 65, March 1959. allowing each business to express its individuality freely and creatively, thereby achieving distinct differentiation between each establishment.

1/

Despite accommodating a diverse array of perspectives, the complex was harmoniously resolved by limiting the intervention of premises from the façades inward. According to this arrangement, premises owners were required to place any commercial advertisements behind glass and to affix their business signage on a solid parapet located at the upper edges. The facades functioned as shop windows, reflecting the predominant tastes and fashions of the time. This strategy resonated with the spirit of the era, where developing and expressing one’s own identity was increasingly important on an individual level.

The same fabric that adorned the shops also extended upwards in front of the slab to conceal the elevated parking lot, boasting a capacity of 150 units. Thus, the complex was perceived as an architectural unit with distinct differentiation between each commercial premise—composed of glass volumes reflecting and absorbing light, scarcely framed by anodized aluminum casings. The passages, paved and devoid of constructions or objects that might disrupt their linearity, accentuated the perspectives and invited individuals to leisurely wander along a path distinct from a mere thoroughfare. This suggests that, conceptually, Pasaje Jacaranda sought to create voids within a solid; in essence, the project comprised the network of routes formed by the aligned and interconnected glass volumes.

The thirty-two commercial premises were affixed along the party walls and aligned with the street. Towards the interior, the usable space expanded, offering flexibility in terms of merchandise display and arrangement through nuanced levels: the entrance and front portion were situated at street level, while the rear strip extended across two heights, one recessed at -1.20 and another serving as a mezzanine at +1.20.

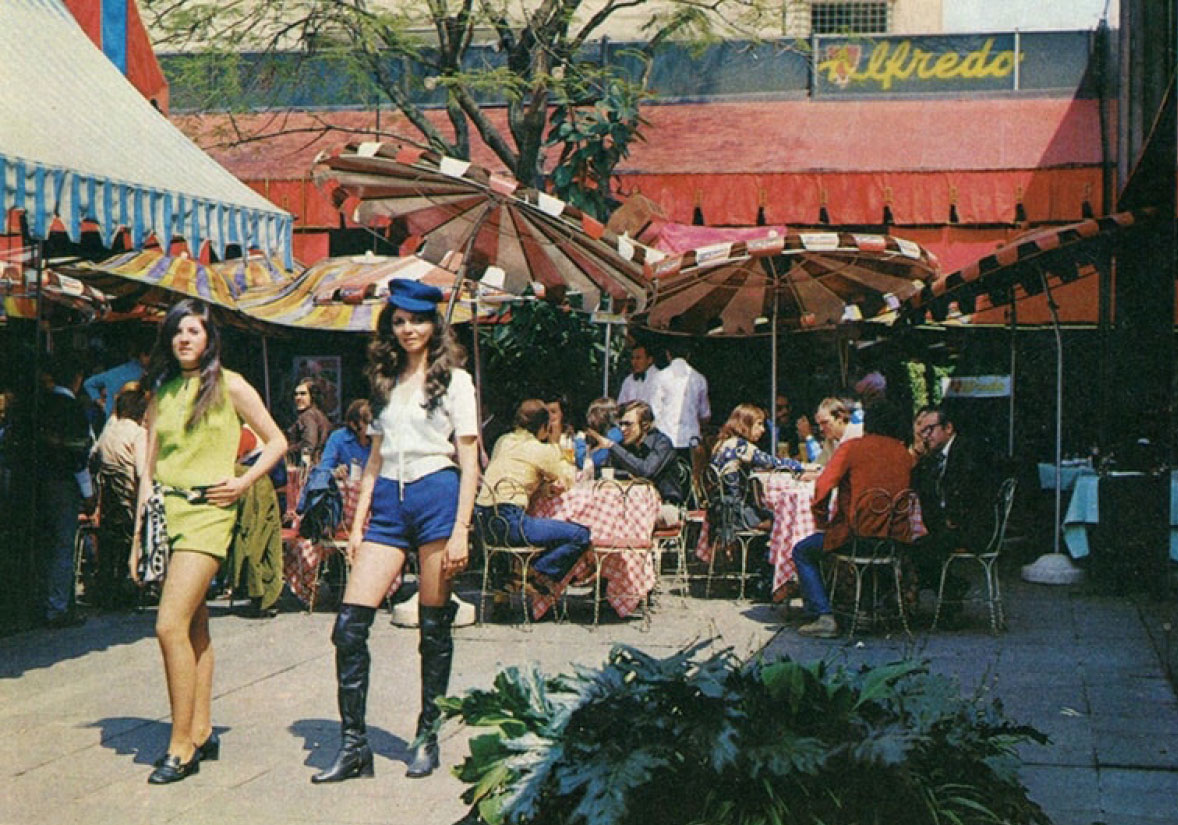

Pasaje Jacaranda was groundbreaking in its characteristics, boasting boutiques, communal areas, gastronomic spaces, and everything deemed essential within a modern shopping center. Many of the commercial establishments played a pivotal role in setting trends or promoting a chic lifestyle, functioning as aspirational settings. Among its most alluring spots was the “Toulouse Lautrec” café, where writers and artists would convene at tables adorned with colorful aluminum umbrellas, occasionally hosting public activations.1515 Carreño Figueras, José. 2013. “Zona Rosa, Mito Rescatado Por La Memoria”. Excélsior. Figures like Mathias Goeritz, Carlos Monsiváis, José Luis Cuevas, and Alejandro Jodorowsky frequented this café. Another notable spot was “El Carmel,” a café renowned for its cultural vibrancy, attracting luminaries such as Carlos Monsiváis, José Emilio Pacheco, and Huberto Batis.1616 Campos, Marco Antonio. “La Zona Rosa En Los Años Cincuenta Y Sesenta – Detalle De Estéticas Y Grupos – Enciclopedia De La Literatura En México – FLM – CONACULTA”. 2018. The café featured a lobby furnished with tables, a lengthy corridor lined with magazine racks and a display-bookcase, and a square-shaped room culminating in a terrace overlooking London Street. Renowned for its Austrian pastries, “El Carmel” often hosted poetry readings and art exhibitions by emerging talents like Lilia Carrillo, Pedro Coronel, and Manuel Felguérez.1717 Ibid.

The restaurants within the complex served a variety of international cuisines, with notable mentions including “Le Bistrot” and “Alfredo.” The former specialized in French gastronomy, boasting an Art Nouveau décor, a spacious terrace, and a grand interior lounge.1818 Riding, Alan. “What’s doing in Mexico City”. New York Times, October 3, 1982. The latter, lauded by the New York Times as the city’s premier destination for Italian cuisine, featured a terrace adorned with cabaret-style chairs, where the Sicilian immigrant owner would often engage in lively conversations with diners.

1/

The Pasaje Jacaranda also featured bars like “La Llave de Oro,” frequented by celebrities and glamorous figures of the era, as well as nightclubs like the “2+2” lounge and the “Jacarandas,” where lively dances with orchestras and live bands were held.1919 Romero Gallardo, Sandra Irais. (2012). “Cambio de uso del suelo y sus repercusiones en la función urbana turística de la Zona Rosa, de 1950 a 2011”. (Bachelor’s thesis). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México. Retrieved from https://repositorio.unam.mx/contenidos/325582. Additionally, galleries such as “Oso Blanco,” directed by Álex Duval, exhibited artwork displayed on easels facing the façade. Furniture stores, jewelry shops, and clothing boutiques were also integral to the complex, with owners meticulously decorating their windows down to the smallest detail. Many of these establishments showcased Mexican-made garments, largely owing to the import substitution development model implemented since the 1940s, which revitalized the Mexican textile industry.2020 Guillén Romo, Héctor. 2013. ” México: de la sustitución de importaciones al nuevo modelo económico”. Comercio Exterior, Vol. 63, No. 4, July-August 2013. Among them was the jewelry store of Guadalajara designer Ernesto Paulsen, who positioned his workshop in front of the store to engage with clients, forging friendships with personalities who frequented the shopping center, regular visitors, and tenants alike.2121 Mora Ojeda, Eloísa. “El diseño de Ernesto Paulsen Camba. Enunciación del modernismo en México” (Master’s thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2010).

As if its prominence in the urban landscape of the time were not enough, Pasaje Jacaranda served as a filming location for movies such as “Las Dos Elenas” (1964), starring Julissa and directed by José Luis Ibáñez, based on a story by Carlos Fuentes, and “Young People in the Zona Rosa” (1970), starring Alberto Vázquez and directed by Alfredo Zacarías. These films depicted daily life inside the Pasaje along with other landmarks of the Zona Rosa, such as the Few Crazy Crocodiles mural by Mathias Goeritz (now destroyed), the Los Castillo silversmiths, and the Konditori restaurant. Furthermore, architectural publications like Calli, Arquitectura México, and Arquitectos de México praised the complex for its innovative and attractive engagement with pedestrians, highlighting the effectiveness of its architecture in showcasing commercial goods. Additionally, Claudia magazine, targeting modern women, promoted the Pasaje and its commercial offerings with slogans like “Distinction in Modern Dresses.”

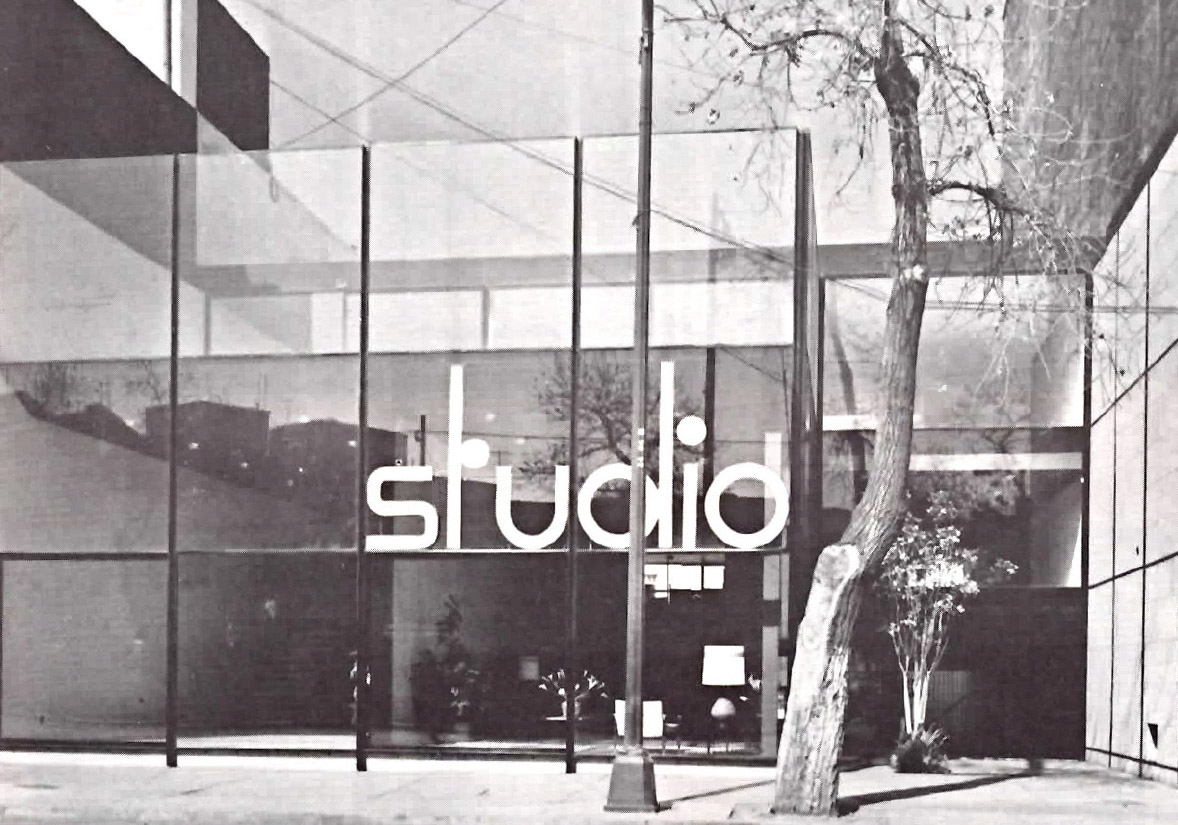

The architectural clarity of the project was evident in other works by the same architects. For the Comercio Studio, located on Insurgentes Sur and completed in 1960, Torres and Velázquez replicated the glass façade of the Pasaje on a larger scale. The building featured commercial spaces at the front and a row of offices spread across three floors at the back. Once again, the slab enclosure was concealed behind this panel, forming a parapet that contained and concealed the rooftop parking. The structure and gates were set back, with the glass forming a continuous plane, but now with a more sophisticated self-supporting structural system.

1/

Pasaje Jacaranda experienced its heyday in the 1960s and 1970s but gradually declined. The avant-garde ambiance that defined it faded away, and each establishment lost its vitality until the entire complex vanished. Many attribute this decline to the construction of the Metro Collective Transportation System in 1967, which brought pedestrian traffic and new dynamics to the neighborhood, driving away the glamorous and aspirational figures that once frequented the shopping center, leading to a loss of interest in the area.2222 Campos, Marco Antonio. “La Zona Rosa En Los Años Cincuenta Y Sesenta – Detalle De Estéticas Y Grupos – Enciclopedia De La Literatura En México – FLM – CONACULTA”. 2018. José Joaquín Blanco noted in one of his chronicles:

“The inauguration of the metro marked the end of Zona Rosa’s dreams. Everything they had envisioned, including the grand square on Insurgentes filled with boutiques and elegant open-air bars, akin to the Côte d’Azur, unless they were to be overwhelmed. And overwhelmed they were, right from the start.

Zona Rosa was quickly, easily, and economically connected to Pantitlán by the metro. The unemployed youth, with a mix of gang member and student vibes, began occupying the exclusive areas. Soon, nothing but perhaps a denser crowd of unsavory characters could distinguish those once elegant streets at night from the murky streets with cabarets of Colonia Obrera or Doctores. Many stores and restaurants fled, in a frenzy, to Polanco. Others survived, with diminished ambitions. Like in the rest of the city, garbage, stray dogs, police officers, thieves, street vendors, beggar clans, ‘chavos banda,’ and ‘street children’ ran rampant.”.2323 Blanco, José Joaquín. 2005. Postales Trucadas. México, D.F.: Nexos Sociedad Ciencia y Literatura.

Moreover, the repression unleashed since ’68, both nationally with social protests and the subsequent Tlatelolco massacre, and internationally with movements like the Black Panther Party, the French May, and student protests in various Latin American countries, led to the displacement and disappearance of spaces for gathering and public discourse, such as Pasaje Jacaranda. Subsequently, the 1985 earthquake prompted many Zona Rosa residents and workers to leave the area due to its soft soil, opting for neighborhoods with lower seismic risk. This mass exodus devalued Zona Rosa and ushered in entirely new businesses and services.

Following its demolition, the properties of Pasaje Jacaranda were replaced by commercial establishments that diverged from the architectural project’s spirit. Today, transnational chain stores like Carl’s Jr. and KFC, and franchises of corporations such as Circle K, Líneas, Tacontento, and Salón Corona occupy the site where the first shopping center once stood. A surviving MixUp store, slightly elevated from the street level, perhaps offers the only reminder of what Pasaje Jacaranda once was, as one of the few remnants not overrun by new construction. Ironically, it now occupies the space that was once a parking lot. Tracing this architectural work in situ is challenging today, as no traces of the buildings remain. Pasaje Jacaranda has been entirely erased from the urban landscape.

1/

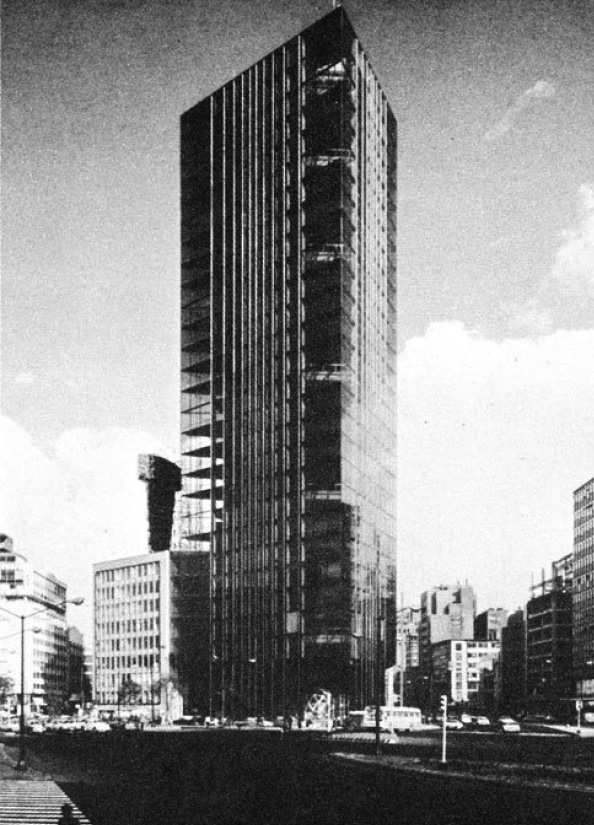

If we view Mexico City as a kaleidoscope with ever-changing facets, the successors to the first shopping center indeed embraced new architectural directions. Plaza Universidad (1969) and Plaza Satélite (1971) emerged in the late sixties through partnerships between real estate developers and specialized department stores. Since the mid-fifties, there had been a concerted effort to ease congestion in the Historic Center by relocating certain functions to other parts of the city, such as the buildings of the National University to Ciudad Universitaria or cultural institutions to Chapultepec Park. By the seventies, the city was experiencing rapid growth, and the densely populated downtown area could no longer accommodate large shopping centers. Consequently, efforts were made to gradually relocate commercial activities to peripheral regions offering larger plots of land and the opportunity for vertical expansion, aligning with the North American model.

Unlike Pasaje Jacaranda, these new developments were situated in areas where urban development was still in its infancy. Both Plaza Universidad and Plaza Satélite, designed by Juan Sordo Madaleno, were positioned along major thoroughfares, ensuring easy accessibility via high-volume roads. Their architectural design featured enclosed perimeter facades and internal pathways lined with spacious walkways. The buildings were significantly larger and taller, with ample space dedicated to parking facilities, providing a sense of exclusivity for car owners. Retail units were smaller in size, and anchor stores such as Sears and Sanborns became prominent features of these complexes.

1/

From the mid-1980s to the late 1990s, shopping centers underwent a process of diversification, incorporating a wide range of products and services along with specialized amenities such as multiplex theaters. Much of this expansion was driven by both local and transnational chains, each with its own distinctive aesthetic that needed to be adapted to the premises they occupied. Merchandise took on new symbolic meanings, and leisure and entertainment activities were housed within newly constructed buildings that often became self-contained environments, with less emphasis on their relationship with the surrounding areas. While Pasaje Jacaranda had broken away from the enclosed spaces of traditional department stores, later shopping centers reverted to inward-focused designs.

In the years that followed, each new shopping center that emerged became a hub of social life and consumer activity, displacing the previous pole of attraction. This pattern mirrored the trajectory of Pasaje Jacaranda, from its inception to its eventual replacement by newer facilities.

- 1 Lozada León, Guadalupe. "¿Cuál Fue La Primera Tienda Departamental En México?". 2021. Relatos E Historias En México. https://relatosehistorias.mx/nuestras-historias/cual-fue-la-primera-tienda-departamental-en-mexico.

- 2 Lash, Scott, and John Urry. 1998. Economías De Signos Y Espacios. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu Editores.

- 3 Gasca-Zamora, José. 2017. "Centros Comerciales De La Ciudad De México: El Ascenso De Los Negocios Inmobiliarios Orientados Al Consumo". EURE (Santiago) 43 (130): 73-96. doi:10.4067/s0250-71612017000300073.

- 4 Héctor Velázquez Moreno (1922 – 2006) and Ramón Torres Martínez (1924 – 2008) formed Torres y Velázquez Arquitectos y Asociados in 1954, working in partnership for over four decades.

- 5 There are several theories about the origin of the neighborhood's name. One of the most popular suggests that Mexican painter José Luis Cuevas described it as such because it appeared red at night and white during the day. Alternatively, it is mentioned that the artist Vicente Leñero named it this way because it was "too timid to be red and too bold to be white." Other sources maintain that the name comes from Carlos Fuentes' "The Death of Artemio Cruz," where the author mentions that the buildings in the neighborhood were painted pink. Finally, there are versions that suggest the name was a way to soften the term "red-light district" with which it was initially known.

- 6 Strukelj, Pedro. “Fachada y variación formal. Análisis de la obra de Ramón Torres y Héctor Velázquez”. Bitácora, no. 14, 2005, p. 60.

- 7 Blanco, José Joaquín. 2005. Postales Trucadas. México, D.F.: Nexos Sociedad Ciencia y Literatura.

- 8 Villasana, Carlos, and Ruth Gómez. “Antes de que hubiera centros comerciales”. El Universal, September 2, 2017.

- 9 Campos, Marco Antonio. "La Zona Rosa En Los Años Cincuenta Y Sesenta - Detalle De Estéticas Y Grupos - Enciclopedia De La Literatura En México - FLM - CONACULTA". 2018. http://www.elem.mx/estgrp/1329.

- 10 Graciela de Garay Arellano. 2000. Historia Oral De La Ciudad De México. México, D.F.: CONACULTA.

- 11 Noelle, Louise. “Retrospectiva de la Obra de Ramón Torres” Arquitectura México, no. 117, 1978, p. 21.

- 12 Ibid.

- 13 Gastón Guirao, Cristina. “Sobre la pista de los fotógrafos de arquitectura en América Latina”. En: Alcolea, R.A, Tárrago-Mingo, J., eds., en el Congreso internacional: Inter photo arch ""Interacciones ``'', Pamplona, November 2-4, 2016.

- 14 s/a. “Pasaje Jacarada”. Arquitectura México, no. 65, March 1959.

- 15 Carreño Figueras, José. 2013. "Zona Rosa, Mito Rescatado Por La Memoria". Excélsior.

- 16 Campos, Marco Antonio. "La Zona Rosa En Los Años Cincuenta Y Sesenta - Detalle De Estéticas Y Grupos - Enciclopedia De La Literatura En México - FLM - CONACULTA". 2018.

- 17 Ibid.

- 18 Riding, Alan. “What’s doing in Mexico City”. New York Times, October 3, 1982.

- 19 Romero Gallardo, Sandra Irais. (2012). "Cambio de uso del suelo y sus repercusiones en la función urbana turística de la Zona Rosa, de 1950 a 2011". (Bachelor's thesis). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México. Retrieved from https://repositorio.unam.mx/contenidos/325582.

- 20 Guillén Romo, Héctor. 2013. " México: de la sustitución de importaciones al nuevo modelo económico". Comercio Exterior, Vol. 63, No. 4, July-August 2013.

- 21 Mora Ojeda, Eloísa. “El diseño de Ernesto Paulsen Camba. Enunciación del modernismo en México” (Master's thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2010).

- 22 Campos, Marco Antonio. "La Zona Rosa En Los Años Cincuenta Y Sesenta - Detalle De Estéticas Y Grupos - Enciclopedia De La Literatura En México - FLM - CONACULTA". 2018.

- 23 Blanco, José Joaquín. 2005. Postales Trucadas. México, D.F.: Nexos Sociedad Ciencia y Literatura.

Pasaje Jacaranda

* Ponencia

¤ Caleidoscopio: Moda e identidad

¬ Museo Universitario del Chopo

∞ abril 2021

Mencionado en: