Where does the history of the architectural heritage of the Bank of Mexico begin? Unquestionably, it starts with its Main Building, which is located at the epicenter of the constellation of buildings that, for almost a century, have housed the functions of one of our country’s fundamental institutions. Due to its long history, this facility has found a place in the imagination of Mexicans as the matrix of operations that support the country’s monetary stability, making it one of the central bank’s main emblems today.

If we trace back to the beginning of its history, we find two key points that contributed to making this a sui generis work: the building was constructed towards the end of the Porfirian period as the headquarters of a foreign insurance company (1905), only to be reborn some years later with a new function within a post-revolutionary national project that sought to establish its own identity (1927). Given the marked differences between these two moments, the creation of the headquarters of the single issuing bank in Mexico required an integrative vision capable of harmonizing divergent architectures, merging temporalities, and projecting messages in line with this ambitious initiative.

The adaptation of an existing construction provided the opportunity to devise a language that reflected a deep understanding of history while introducing novel and unprecedented aesthetic codes. This approach maintained a connection with the past and a commitment to the future. These challenges were addressed at various levels of integration, covering multiple scales and benefiting from the amalgamation of knowledge and the creative, artistic, and engineering skills of collaborators who were fully involved in this initiative.

1/

Through archival materials and interactive resources, this exhibition presents the journey undertaken to shape the comprehensive project. Considering this building as an evolving entity that has endured and resurfaced multiple times in response to its users and those who have influenced its design, we present reflections from artists and architects who, in our time, highlight its exceptionality and heritage value. These approaches invite us to continue exploring the various layers of history that constitute this essential piece of our architectural legacy.

The Temporary Building

The Main Building has become such an emblematic icon that it is difficult to imagine Banco de México starting operations elsewhere. Although the choice of this building was made by the Álvaro Obregón administration, the purchase procedures and adaptation works took more than four years to complete. This lengthy process forced officials to look for a temporary headquarters nearby. Thus, in 1925, the ground floor of the Bank of London and Mexico building, at the corner of September 16 and Vergara (now Bolívar), was leased for two years, where the inaugural ceremony of the newly founded central bank was held.

Designed in 1912 by Miguel Ángel de Quevedo, the building stood out for its majestic façade with Ionic columns, a diamond skirting board, and relief sculptures of organic motifs and human figures. However, what made it truly famous was its underground vault, an engineering feat successfully built in the capital’s muddy soil. This feature played a crucial role in Banco de México’s choice, requiring a safe place to protect valuables. Even after its establishment, Banco de México continued to lease part of that vault to the Bank of London and Mexico until its space needs were resolved.

The Outside

The construction industry was paralyzed after the Mexican Revolution due to the ravages of the conflict, while the bankruptcy of numerous owners left several properties abandoned. This gave rise to a new perspective that advocated reusing existing constructions instead of building new ones. Thus, the federal government embarked on a search for buildings that could house the operations of the future Banco de México and identified two candidates previously occupied by insurance companies: one was the iconic La Mexicana building, known for its striking tower with a clock on top, and the other was the Mutual Life Insurance Company building, which was ultimately chosen.

Erected at the beginning of the 20th century, La Mutua—as it was colloquially known—was part of the set of imposing buildings completed during the sixth presidential term of Porfirio Díaz (1904-1911), which sought to highlight the country’s cultural grandeur through eclectic architecture. This style, prevalent for decades, involved incorporating European academic models from different historical periods into a single style.

During the initial stages of designing the Main Building of Banco de México, it was concluded that the existing space would not be sufficient to accommodate all the anticipated needs. To meet the required space and implement the proposed architectural program, which included an underground vault, it was decided to expand the building to more than half of its original volume. This integration of new functions transformed a slender rectangular prism into a robust quadrangular volume.

The Previous Building

During the Porfiriato, insurance companies were among the most successful, thanks to their extensive portfolio of businessmen. The Mutual Life Insurance Company, founded in New York in the mid-19th century, expanded its operations to Mexico in 1886, responding to the invitation of Porfirio Díaz and joining the wave of foreign companies that established themselves in the country under the initiative of the Secretary of the Treasury, José Yves Limantour.

For the design of its headquarters in Mexico, the invited architects, Theodore De Lemos and August W. Cordes, incorporated typical ornaments and motifs they used in buildings they constructed in American metropolises. The iron skeleton, composed of a grid system of joists, was designed by Gonzalo Garita and manufactured and imported from Chicago by the Milliken Brothers. The façades featured ashlars with recessed joints, typical of the Italian Renaissance. In its central body, four imposing Ionic columns extended from the first to the third level, framing five windows with semicircular arches.

In the main lobby, two elevator shafts flanked a large corridor, and on both sides were doors that gave access to the office area. This axis ended with an imperial staircase covered in marble, with ironwork railings inspired by the French Renaissance. It began with a ramp aligned with the central corridor and then branched into two semicircular ramps that ascended to the next level.

With more than 5,940 square meters of total space inside, the insurer subleased more than 100 commercial premises, which was an unusual business model in the country but quite widespread in the United States.

The Expansion

For more than a decade, La Mutua maintained its activity until the insurance company declared bankruptcy in 1922, and gradually the tenants were evicted from the building. At that time, Carlos Obregón Santacilia, who had recently completed his training as an architect, was invited to design the headquarters of the Bank of Mexico, which would eventually catapult him as one of the most prominent architects of his time. The contract also included the engineer Federico Ramos to solve and direct the construction systems, while the distinguished architect and urban planner Carlos Contreras was later summoned to supervise the work.

In his initial attempts, Obregón Santacilia chose to preserve the prominent semicircular staircase that belonged to the original building. However, after several schemes, the four rows of windows that looked toward the new National Theater were expanded to seven, and vehicular access was enabled adjacent to the Postal Palace. On the opposite façade, which faces the Zócalo, five rows of windows were added to the existing three, and exclusive access to the upper floors was added at the rear. Following these changes, the architect placed the staircase at the back again, now in a new location that faced a larger building.

For this extension, the same white quarry stone from Izuantla, Hidalgo, used in 1905, was utilized, with minimal adjustments made to the main façade. One of the most notable changes was the removal of ten caryatids, which were replaced by square pilasters, and the addition of a sculptural group of seated figures by Manuel Centurión where previously there were a pair of lamps with spherical shades. The ground floor and basement windows were covered with wrought iron bars to protect the valuables and give a sense of security and strength. The lion masks were reorganized to fit the new design, maintaining the same sequence but leaving a space between each one.

Additionally, the structure on the west side was maintained and replicated on the east side to achieve the symmetry proposed by the expansion. This involved reinforcing the original columns with concrete and recalculating the building loads for proper distribution in the new structure. Finally, a portion of the first-level mezzanine was removed to create a spacious lobby with a height of eight to nine meters, ideal for serving hundreds of customers a day. These changes to the interior diverged from the original design, creating a spacious and versatile space—a blank canvas that invited Obregón Santacilia to carry out a radical transformation.

Inside

During the design process of the Main Building, painters, sculptors, and artisans were incorporated into the project, who conceived artistic elements with messages alluding to progress and modernity, integrally fused with the architecture. This approach represented a fundamental change from the Porfirian tradition and its predecessor of adding works of art to a building after its construction. Instead, it embraced the trend of Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total work of art” (a translation of the German term), establishing a precedent for movements that emerged in subsequent years, especially for the plastic integration that reached its peak around the mid-20th century.

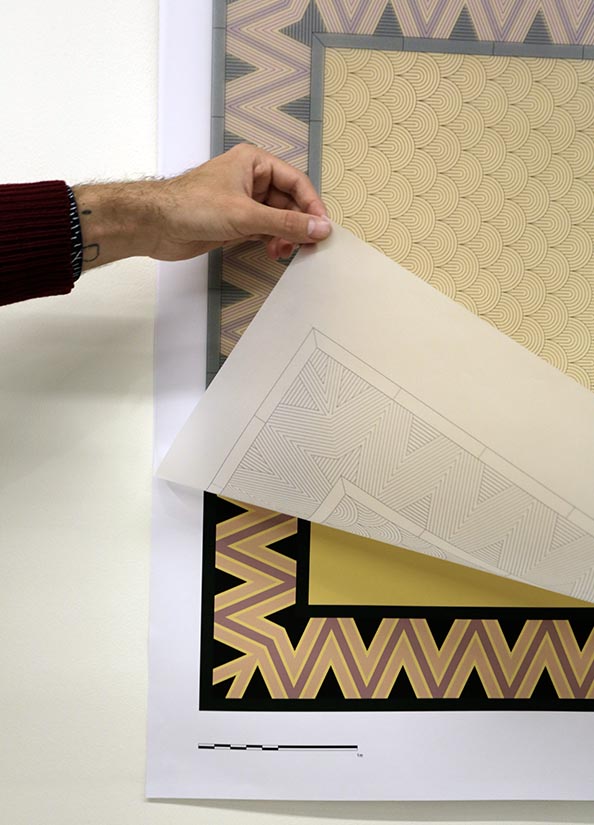

Obregón Santacilia’s discreet architectural intervention in the shell of the building contrasted significantly with his efforts to generate a new building on the inside, where his own stamp would be reflected. His attention to detail included designing each component of the architecture from scratch, addressing aspects ranging from the meticulous design of the railings and balusters to the graphic identity of the Bank of Mexico.

1/

Unlike the exterior, whose architecture was retrospective in nature, the architect opted for an unprecedented language in the interior. Thus, both he and his collaborators were inspired by various artistic and architectural currents of their time, which resulted in formal and spatial solutions that captured the essence and contingent expressions of their era. Together, these components turned the interiors of the property into a pioneering case—both locally and worldwide—of the style that decades later would be called Art Deco.

The Remodeling

At the dawn of the 20th century, architectural movements such as Art Nouveau flourished in many cultural capitals. However, in Mexico, these movements contrasted with the ossified eclectic tradition and barely manifested themselves, often diluted among older styles without standing out as a distinctive proposal.

Simultaneously, architects trained at the Academy of San Carlos were embracing the international avant-garde. They were inspired by the integration with nature and the use of organic lines present in the buildings of the renowned American architect Frank Lloyd Wright; by the pursuit of smooth surfaces, tubular structures, and unadorned materials of the Viennese Secession led by architect Otto Wagner; as well as by the dynamic forms and futuristic elements of expressionist architecture in Germany. Additionally, they absorbed the ideas of the influential Austrian architect Adolf Loos, who questioned the use of decorative ornaments in architecture throughout history.

In the same year that the project for the Main Building of the Bank of Mexico began, the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts took place in Paris, an event that left a deep mark on the history of design and architecture. During this period, archaeological remains were discovered in ancient cities, revealing geometric graphic motifs and visual patterns that were later synthesized into components of contemporary buildings and utilitarian objects. At the same time, in densely populated cities in the United States, skyscrapers were built with staggered setbacks at certain heights due to zoning codes.

These influences and currents were reflected in the Banco de México building, transforming it into a symbol of architectural innovation. Stucco coatings were eliminated in favor of exposed materials, such as imported marbles and shiny metals. The walls were designed with staggered panels, octagonal columns with rectilinear Ionic capitals with vertical flutes were used, and octagonal shapes were adopted in the lamps, while simple and angular lines defined the patterns of the railings, balusters, and floors.

The Collaborations

During his tenure, José Vasconcelos entrusted Carlos Obregón Santacilia with his first architectural projects, beginning with the design of the Mexican Pavilion at the International Exposition in Rio de Janeiro. The collaboration extended to the Benito Juárez School Center, where the Secretary of Public Education expressed his preference for inviting artists to incorporate large-format paintings in public buildings, which would consolidate the Mexican state and forge a new identity.

Obregón Santacilia adopted a similar approach in his career as an architect, collaborating closely with painters and sculptors. In the Main Building, Hans Pillig and Manuel Centurión were in charge of the sculptural work, which included four friezes in the lobby, reliefs on the walls of the hall, and one of the most prominent features of the building: the ceiling containing six caissons with decorative bas-reliefs of human figures symbolizing work, abundance, and the desire for prosperity. At the center of these caissons, an amber-toned skylight with brittle lines and spikes was designed by Victor F. Marco.

In these years, Estridentismo was in full swing, an artistic movement disseminated largely through periodical publications such as Crisol Revista de Crítica, which had a revolutionary and Marxist nature and whose covers were created by Fermín Revueltas. In addition to his work as an illustrator, Revueltas also produced murals, easel paintings, vignettes, and later specialized as a stained glass artist. Gonzalo Robles, who had also collaborated with the magazine, invited Revueltas to work on a series of private and public projects at the beginning of the 1930s. Later, when Robles began his brief tenure, he commissioned Revueltas to create a stained glass window for the staircase of the Main Building. However, the original work was not carried out due to the artist’s premature death. Decades later, with the opening of the Banco de México Museum, a digital reproduction was made in the place where it had been planned.

The Urban Context

The Main Building of the Bank of Mexico has undergone multiple transformations throughout its history, adapting to changing urban circumstances. Initially, the Mutual Life Insurance Company acquired land that had previously housed the convent of Santa Isabel to establish its offices. However, towards the centenary of Independence, the government expressed interest in this property to build a new headquarters for the National Theater (today the Palace of Fine Arts). This led to a formal agreement in March 1902 through an exchange: in return for the old convent site, the adjacent property, located on the other side of Santa Isabel Street and bounded to the east by Condesa Alley, was given.

The location of the building in this area was strategic as it was integrated into an urban reorganization program that included the modernization of public lighting, repaving, and reconfiguration of the streets and avenues in the area. Years later, after the expansion and remodeling to house the single issuing bank, increasingly organized urban plans covered the peripheral neighborhoods of the Historic Center, generating an expansion of the city. During this period, the urban planner Carlos Contreras designed the regulatory plan for the Federal District, a milestone in the urban development of the capital.

Despite the prominent height of the Main Building and the consistent scale of the surrounding buildings, a decade after its inauguration, nearby areas began to see the construction of the first modern skyscrapers and a diversification in the architectural styles that coexisted. Added to this expansion was the growth of Banco de México itself, which found it necessary to locate its operations in a new building outside the limits of the Main Building, an expansion that would gradually increase in the subsequent decades.

Evolution of the City

In 1901, the Minister of Finance, José Yves Limantour, announced a substantial investment of 10 million pesos for the extension of Avenida 5 de Mayo, where the main façade of the building is located. This ambitious project aimed to transform the avenue into a modern public space to attract Porfirian high society. This initiative made it the widest road in the country and led to the creation of a new commercial axis where restaurants, tailor shops, fashion houses, coal stores, and pharmacies flourished.

This initiative had a significant impact on the surrounding architecture, giving rise to a series of emblematic buildings in the city. Porfirio Díaz used this area to house palatial architectural jewels, such as the Secretariat of Communications and Public Works, the Post Office Palace, and the Grand National Theater, the latter designed by the renowned architect Adamo Boari and involving some of the main builders and structuralists of La Mutua.

Shortly after the opening of the Main Building, eclecticism began to fade with the new constructions in the city, and the Art Deco style started to gradually spread to the surrounding buildings’ architecture, creating an urban landscape with a consistent architectural language. However, the visionary architects such as José Villagrán quickly displaced this style, and other styles emerged, such as Functionalism and the Modern Movement, which reached their peak in the mid-20th century and dominated the Mexican architecture scene.

A New Building

A decade after its construction, the Main Building faced a shortage of space, especially in its vaults. In response, the construction of new vaults on nearby land was proposed. Carlos Obregón Santacilia designed a new building for the adjacent property at the intersection of 5 de Mayo streets and Condesa Alley. The objective was to maintain the scale and height of the Main Building, incorporating some of its characteristic elements and adding new forms. However, this project was rejected due to the landowner’s unaffordable demands.

Faced with this situation, the strategy changed, and it was decided to acquire another piece of land—which included the house known as Guardiola and two adjacent buildings—located on the other side of the block. Initially, it was considered to create only a plaza with underground vaults on this property, but later it was decided that it should become an architectural landmark that would serve as a fitting endpoint for Juárez Avenue and Alameda Central. Obregón Santacilia adapted the design he had worked on to this block, resolving a volumetry similar to the Main Building and combining elements of the Art Deco style with early signs of architectural movements that would later come into vogue.

For Obregón Santacilia, it was essential to design a large plaza that would allow a full view of the Main Building and the surrounding architectural landmarks, contributing to the growing urban landscape. The square was located where Guardiola’s garden was previously situated, the old Condesa Alley was expanded and extended to its sister building, the first official building of the Bank of Mexico, creating a visual connection between both and their respective blocks. This gave the city a new image that was interwoven with the Main Building.

Contemporary Approaches

Just as Obregón Santacilia approached a pre-existing building in 1925, this exhibition invites diverse perspectives to interact with the Main Building from its history and heritage value.

1/

The Main Building of the Bank of Mexico is not only a historical landmark but also a dynamic space that continues to inspire contemporary architects and artists. This exhibition features contributions from five architecture firms and two contemporary artists, each bringing their unique perspective to the building’s legacy and creating works that engage with its rich history and architectural significance.

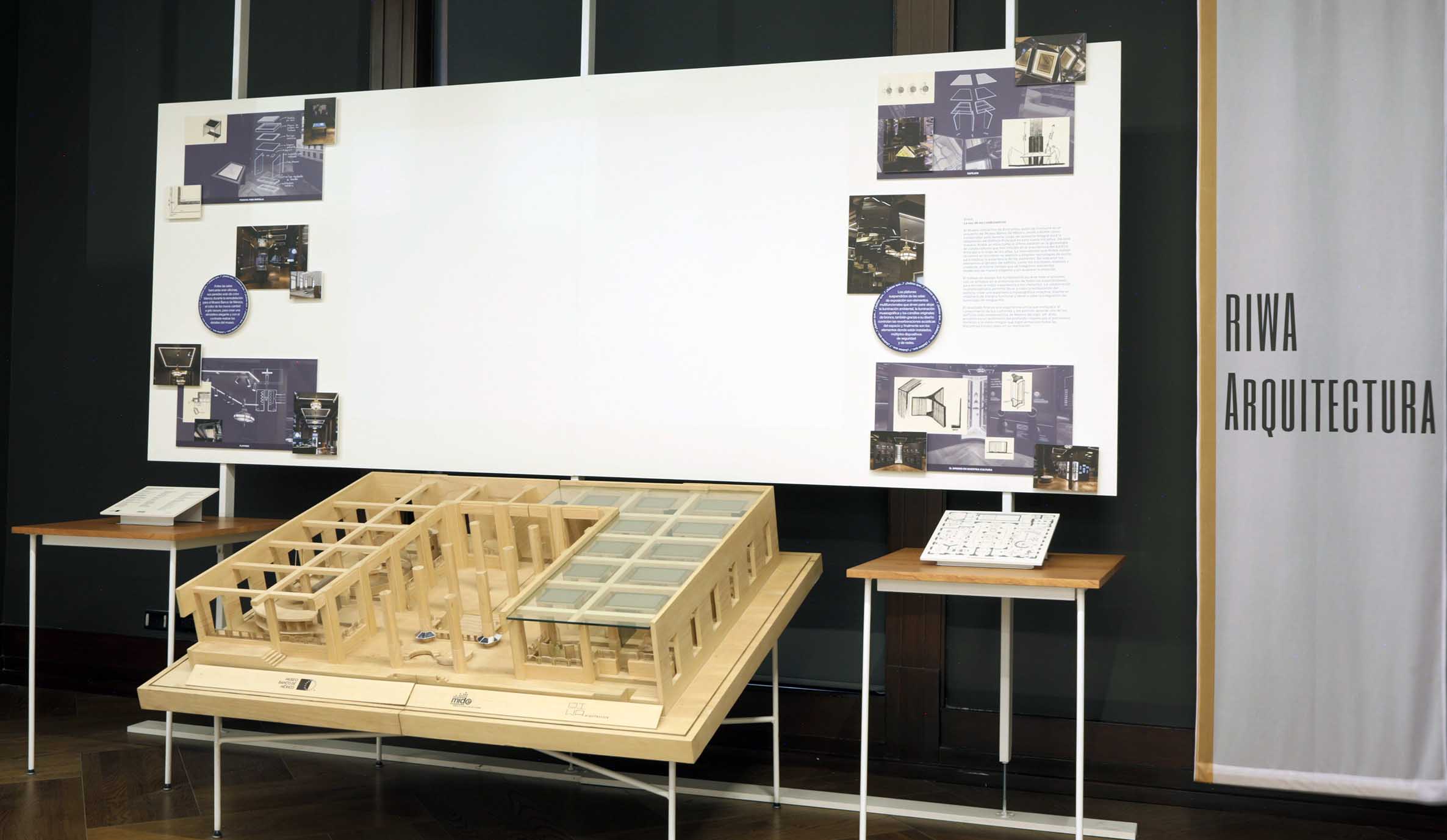

LANZA Atelier is known for their interventions in heritage public spaces, transforming them into vibrant meeting places. Their approach is characterized by a deep respect for historical context, combined with innovative design that fosters community interaction. Escobedo Soliz excels in transforming spaces through subtle interventions that adhere to common construction criteria, emphasizing minimalistic changes that enhance the existing architecture while maintaining its integrity. Estudio estudio specializes in projects that blend art, architecture, and culture, demonstrating a keen sensitivity towards construction materials and integrating artistic elements that elevate the architectural experience. PALMA enhances the architecture of buildings and activates public spaces through playful designs that encourage public engagement and bring a sense of joy and creativity to urban environments. RIWA Architecture played a crucial role in designing the Banco de México Museum, balancing preservation with modern functionality through careful intervention.

Marco Rountree, a contemporary artist renowned for his ability to reinterpret artistic and architectural milestones, often involves a critical dialogue with historical contexts, reimagining them in contemporary terms. Darinka Lamas creates deep connections with the spaces she engages with, from the smallest rooms to entire cities, characterized by an intuitive understanding of the spatial and cultural dimensions of her surroundings.

Each participant has approached the Main Building from their unique perspective, creating interventions, installations, or pieces that establish a dialogue with the archival material on display.

Architectural integration

* Exhibition

+ Exhibiting artists and architects:

Darinka Lamas

Escobedo Soliz

estudio estudio

LANZA (Arienzo + Abascal)

Marco Rountree

P A L M A

RIWA Arquitectura

Exhibition design:

Ali Silva

Paulina Maya

Development:

Oficina de Exposiciones MBM

¬ Museo Banco de México

∞ November 2023 – February 2024

Featured on:

UnoTV

La Crónica

Caras

Sopitas

Chilango