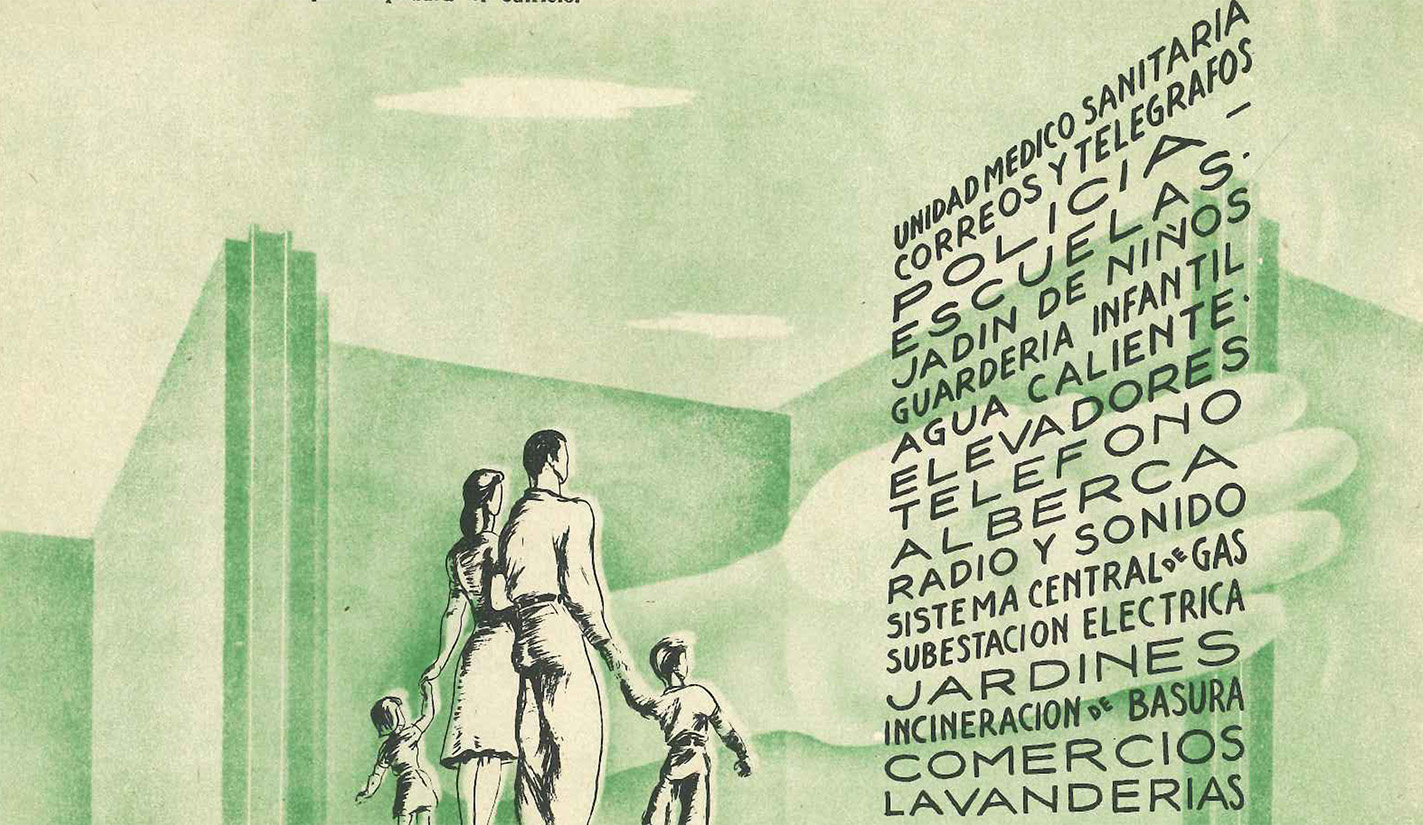

The Presidente Alemán Urban Center (CUPA) represented a milestone in Mexico’s urban development, embodying modernist ideals and innovative urban planning concepts. Designed by Mario Pani and overseen by the Associated Civil Engineers (ICA), CUPA was a superblock model integrating various facilities within a cohesive community. Completed in 1949, it offered a comprehensive living environment with amenities including housing, workspaces, commerce, education, and sports facilities. Situated on the southern outskirts of Mexico City, CUPA heralded a new era of urban expansion and modern living, symbolizing the country’s aspirations for a futuristic, organized, and healthy capital.

Driven by a post-revolutionary ethos and a vision of urbanization promising modern amenities, State-led efforts under administrations like Manuel Ávila Camacho and Miguel Alemán Valdés culminated in projects like CUPA. Architects such as Juan Legarreta and Enrique Yáñez spearheaded early initiatives like Lascuráin Park and El Buen Tono, laying the foundation for Mexico’s multifamily housing revolution. With its completion ahead of schedule in 1949, CUPA epitomized modernist principles, marking a paradigm shift towards urban expansion and a futuristic vision for Mexico City’s development.11 Mario Pani, Los multifamiliares de Pensiones (Mexico City: Editorial Arquitectura México, Cooperativa de los Talleres Gráficos de la Nación, 1958), 8.

On September 1, 1949, Carlos Monsiváis’s prophetic statement came to fruition: “multifamily housing is the modern utopia of Mexico without neighborhoods.” This marked the onset of urban expansion towards the southern outskirts of the city, epitomizing the quest for a futuristic, organized, and healthy capital.22 Carlos Monsiváis, No sin nosotros. Los días del terremoto 1985-2005 (Mexico City: Era, 2005), 84.

1/

The CUPA project embodied a new city within the city, demanding meticulous intervention at every scale. Pani assembled a multidisciplinary team of specialists and advocated for the creation of furniture tailored to the apartments. To achieve this, he enlisted the expertise of Clara Porset, a designer whose advocacy at the time focused on addressing the housing challenges posed by the capital’s slums and neighborhoods. Porset laid the groundwork for her own utopian vision, proposing dignified domestic spaces within a project slated to accommodate over five thousand people across 1,080 apartments.

Given the project’s ambitious scope, the furniture pieces needed to meet three key criteria: affordability to align with CUPA’s budget constraints, scalability to efficiently cater to the volume of apartments, and adaptability to accommodate various housing layouts. Porset, accustomed to intervening in projects midstream, meticulously defined shapes, textures, proportions, and materials. Instead of merely adding objects, she integrated new architectural elements that harmonized with the space, striving for what she termed “organic unity.”33 Ana Elena Mallet et al., Inventando un México moderno. El diseño de Clara Porset (Mexico City: Turner/ Museo Franz Mayer/ UNAM, 2006), 158. Clara Porset’s design sensibilities closely aligned with those of modern architects, leading to collaborations with luminaries such as Mario Pani, Enrique del Moral, Luis Barragán, Enrique Yáñez, Max Cetto, Juan Sordo Madaleno, Carlos Lazo, and Enrique de la Mora, among others. Months after completing the furniture for the multifamily project, Porset emphasized in a conference that “space remains empty until defined, interrupted, and molded with materials.”44 Clara Porset, Espacio, luz y belleza dinámica, Mexico City, January 1949.

Mario Pani envisioned four distinct types of units tailored to accommodate the varied needs of the families residing in the apartments. Each unit’s dimensions and layout were meticulously designed to suit different interior spaces. In line with this typological variability, Clara Porset followed suit in her approach to designing furniture for the apartments. She ensured that the furniture possessed the necessary flexibility to adapt to the diverse environments and uses they would encounter.

The majority of homes spanned two levels. One level was designated for the living room and bedrooms, while the other, serving as the access area, housed the kitchen and dining room—a space historically revered as the nucleus of hospitality in Mexican culture. Porset ingeniously crafted a table with folding sections on each side, facilitating easy expansion to accommodate visitors. Additionally, she designed a pair of tables—of equal proportions—where the taller one functioned as a side table, conveniently reachable while standing, while the lower one served as a coffee table, blending seamlessly into the room’s ambiance. Complementing these pieces was a modular bench that offered versatility in use, allowing for various configurations to suit different needs.

1/

Clara Porset’s meticulous approach extended to a set of chairs designed to accommodate various postures, each tailored for different activities: straight-backed for dining or working, slightly inclined with armrests for conversation, and reclined and lower for reading or resting. Additionally, she conceived a versatile sofa bed that seamlessly transitioned from seating during the day to sleeping quarters at night, adaptable to both living rooms and bedrooms.

Porset’s ingenuity further manifested in three types of modular dressers, each varying in compartmentalization: one with front-facing double doors, another featuring lower doors to house a top drawer, and a third boasting three drawers. These dressers could be strategically placed and combined to suit different spaces, serving purposes ranging from dish storage in the dining room or kitchen to housing personal belongings in the bedrooms.

Driven by a passion to reclaim Mexico’s artistic heritage, Porset ideologically aligned with the muralists’ desire to impart a nationalist essence to modern architectural interventions. This modern-regional approach deemed it essential for the multifamily project to incorporate traditional forms, fostering a collective spirit among its inhabitants.55 Clara Porset, “El Centro Urbano Presidente Alemán y el espacio interior para vivir,” Arquitectura/ México 32 (October 1950): 117. Furniture manufacturing embraced artisanal techniques and indigenous raw materials, including pine and cedar woods, tule, and palm fabrics, imbuing the pieces with both symbolic and practical significance.66 José Roberto Gallegos Téllez Rojo, La artesanía, un modelo social y tecnológico para los indígenas. Política y Cultura (Mexico City: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, 1999).

Lo anterior significó ventajas considerables: en el plano simbólico, acentuaba valores y reflejaba una identidad nacional que el Estado benefactor buscaba forjar como vía para alcanzar la verdadera modernidad, y en el plano de producción la apuesta resultaba sumamente rentable. Por un lado, el uso de materiales locales reduciría gastos de transporte y una inversión más baja debido a que la política de sustitución de importaciones proveía subsidios a productos y manufactura mexicana; por otro lado, el empleo de manufactura artesanal e industrias nacionales en función de los altos volúmenes de producción que se darían tendría que reducir costos de forma drástica.

This approach yielded notable advantages: symbolically reinforcing national identity in line with the welfare state’s pursuit of true modernity, while economically leveraging local materials and artisanal production to reduce costs. However, despite these potential benefits, and perhaps constrained by budget considerations, it was ultimately decided not to furnish the apartments but instead offer the furniture separately to tenants. This shift led to increased per-piece costs, potentially limiting acquisition opportunities.

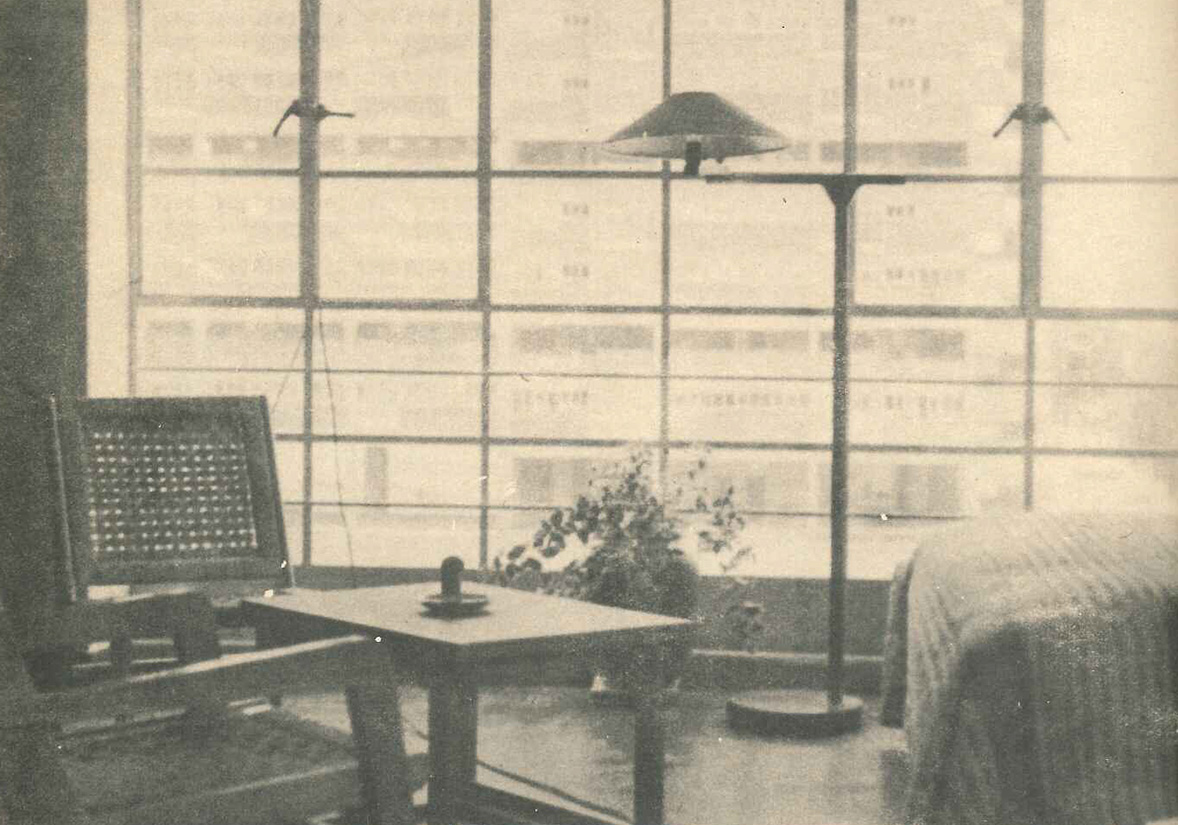

To generate interest among prospective tenants, three “show apartments” were meticulously outfitted, showcasing the layout and utility of Porset’s furniture alongside complementary accessories such as curtains, glasses, books, and lamps. These images captured the essence of Porset’s designs and underscored the spatial potential of the homes, despite their modest square footage. Yet, in hindsight, these photographs served as a poignant reminder of the gap between utopian aspirations and practical realities, highlighting the inherent challenges in bridging the divide between idealized visions and tangible outcomes.

1/

One year after its inauguration, the CUPA surpassed expectations, housing seven thousand tenants by 1950. Mariano Picón Salas vividly captured the scene of new inhabitants arriving with their belongings, symbolizing the beginning of a new chapter filled with hope: “the freight elevators carrying the modest furniture of the families who will build a new and hopeful life here are full.”77 Mariano Picón-Salas, “Vivienda para muchos,” Arquitectura/México 31 (May 1950): 56. Clara Porset, reflecting on her work, highlighted the pivotal role of furniture in shaping interior spaces and fostering a cultured atmosphere:No matter how solid and complete a room is in its architectural design, it cannot fully meet the requirements of good living without thoughtful organization and utilization of furniture. Furniture and equipment are inherently linked to the interpretation of architecture and industrial design, essential in creating a cultured atmosphere that elevates daily life through the scientific design of standardized production. The furnished apartments, numbering over a hundred, represent a bold and progressive step towards dignified and creative living. While these interior spaces could be further enhanced, they already embody a wealth of effort and innovative ideas, making them livable spaces in their own right.88 Porset, “El Centro Urbano ‘Presidente Alemán’”.

Despite numerous promotional efforts, only 10% of the homes in the CUPA were furnished with Clara Porset’s designs. Years later, with the multifamily complex fully inhabited, Porset expressed discontent that most tenants brought their old furniture or acquired new, ostentatious pieces to conceal deficiencies. She perceived these interiors as a departure from her vision, influenced by commercial pressures from advertising, cinema, radio, and television, resulting in spaces devoid of the furniture’s intended expression.99 Clara Porset, “Diseño viviente. Hacia una expresión propia en el mueble,” Espacios. Revista integral de arquitectura y artes plásticas 16 (March 1953).

The resistance among Mexicans to abandon traditional lifestyles, evident in their reluctance to replace belongings when moving into new multifamily complexes, runs deep. Beyond mere financial concerns, the items they brought symbolized their identity, serving as personal touchstones in an unfamiliar environment. For new tenants, the modern housing complex represented both progress and threat: a symbol of the state’s advancement, yet a challenge to deeply rooted habits and customs.1010 Graciela de Garay Arellano, Modernidad Habitada (Mexico City: Instituto Mora, 2004). This duality was palpable in the struggle to reconcile the surrounding rural landscape with the mechanized efficiency of the complex, underscoring the tension between modernization and individuality.

Clara Porset references a pivotal moment in modernization when mass media experienced a significant expansion, granting it unprecedented influence over the cultural landscape. Spearheaded by the United States, this surge in media, including cinema and other broadcast platforms, reclaimed the spotlight after the economic upheaval of World War II. The collective imagination of the American Way of Life subsequently permeated aspirational domestic settings, catalyzing a process of transculturation with foreign objects. Emphasis was placed on adapting to modern, mechanized household tools, reshaping daily life.

A prime example of this cultural shift was evident in popular consumer newspapers and magazines, which showcased international designs and served as vehicles for propaganda, dictating the organization of home interiors. Publications like Hortensia introduced readers to avant-garde decorations, Femenil advocated for modernizing dining spaces while maintaining contemporary taste, and Orquídea offered guidance on bedroom redecoration based on children’s growth stages.1111 Anahí Ballent, “La publicidad de los ámbitos de la vida privada. Representaciones de la modernización del hogar en la prensa de los años cuarenta y cincuenta,” México Alteridades 6, no. 11 (1996): 53-74. Niche editions such as Arquitectura/México, Calli, and Espacios furthered the dissemination and promotion of art, architecture, and innovative housing construction. These modern publications played a pivotal role in shaping the trajectory of the future.

Mexican cinema of the era depicted narratives of love and social ascent against backdrops of contrasting social strata, slums, and burgeoning colonies. Preceding the emergence of CUPA, blockbuster films like “Enamorada” (1946) and “Salón México” (1948) by Emilio Fernández, “Champion without a Crown” (1946) and “Una Familia de Tantas” (1948) by Alejandro Galindo, and “Aventurera” (1949) by Alberto Gout portrayed neighborhood life, showcasing modest communities juxtaposed with opulent residences adorned in French motifs. These luxurious houses, replete with ornate moldings, elaborate textures, and robust furniture echoing baroque and nouveau avant-garde styles, represented simulated environments influenced by the clichés of the Porfirian bourgeoisie. These settings served to reinforce archetypal distinctions supporting the lifestyles of the upper echelons of society.

Such socially constructed dispositions became ingrained as habitus, reflecting learned patterns from prevailing social structures. From the domestic sphere outward, these patterns aimed to emulate the hierarchical ideals prevalent within the social hierarchy of the time.1212 Pierre Bourdieu, La distinción. Criterios y bases sociales del gusto (Madrid: Taurus, 1988).

1/

The families who moved into the CUPA primarily consisted of state bureaucrats, administrators, teachers, postal workers, secretaries, and drivers, among others. Many of these professionals belonged to the middle class and aspired to structure their living spaces based on social categories often expressed in everyday language as “good family” or “decent people.”1313 De Garay, Modernidad Habitada, 108. A significant number of tenants furnished their apartments with wardrobes, chests of drawers, and bulky closets made of sculpted wood, diverging from the regional and modern aesthetic that CUPA aimed to embody. While some aimed to economize, others were hesitant to embrace new ways of inhabiting domestic spaces, opting instead for familiar representations of social status.

Ironically, much of the capital’s elite looked down upon the simple and purely functional aesthetics of this furniture. Conversely, folkloric and vernacular styles became the habitus of the more privileged sectors, embodying values perceived and recognized primarily by those with a certain cultural capital. Although many of Porset’s designs were later consumed by these sectors, she expressed deep dissatisfaction with the reality where quality furniture became “the exclusive prerogative of the highest classes.”1414 Porset, “Diseño viviente”. Initially, the motivations behind the design of furniture for CUPA were fundamentally social. Porset was concerned about the dismal living conditions experienced by the majority of Mexicans and was dissatisfied with the fact that two-thirds of the population lived in deplorable conditions.1515 Porset, “El Centro Urbano ‘Presidente Alemán’”.

She firmly believed in the transformative power of design, envisioning that decent furniture could play a crucial role in addressing social issues such as overcrowding and unhealthiness. Moreover, she believed that quality interiors could positively influence the development of the users.

Although Porset’s utopian vision was not fully realized amidst the numerous successes of her prolific career, the ideals that inspired her remained evident in each of her works. Her designs, both preceding (such as the Organic Design for Home Furnishing for the Museum of Modern Art in New York) and succeeding CUPA (modern residences), adhered to basic principles of standardization, modulation, and interchangeability. Her creations extended beyond furniture for homes to encompass schools, hotels, factories, and offices, reflecting her democratic approach to design.

Porset’s unique personality was shaped by influences such as Henri Rapin, Josef and Anni Albers, her time at Black Mountain College, her relationship with her husband Xavier Guerrero, and her upbringing in the tropical climate of Havana. She advocated for “interior design” over “interior decoration” and successfully integrated her creations into various spaces across modern Mexico. In “Living Design: Towards an Expression of Furniture” (1953), she lamented that “Mexico lost its first opportunity to comprehensively confront the problem of low-cost living.”1616 Porset, “Diseño viviente”. Behind this disappointment lay her unwavering and fervent pedagogical vocation, coupled with a positivist idealism regarding popular art and design’s potential to effect change and improvement in living conditions. This was the essence of her inner utopia: to prioritize ergonomic, functional, and aesthetic furniture for modern humanity, thereby sowing the seeds for a new housing model. At that time, the modern utopia had only begun to take root within the CUPA complex and its surrounding urban landscape.

The translation from the original Spanish text was completed with the assistance of AI tools due to limited resources for professional translation. Although efforts have been made to ensure accuracy through careful review and adjustment, some imperfections may still exist in this translated version.

- 1 Mario Pani, Los multifamiliares de Pensiones (Mexico City: Editorial Arquitectura México, Cooperativa de los Talleres Gráficos de la Nación, 1958), 8.

- 2 Carlos Monsiváis, No sin nosotros. Los días del terremoto 1985-2005 (Mexico City: Era, 2005), 84.

- 3 Ana Elena Mallet et al., Inventando un México moderno. El diseño de Clara Porset (Mexico City: Turner/ Museo Franz Mayer/ UNAM, 2006), 158.

- 4 Clara Porset, Espacio, luz y belleza dinámica, Mexico City, January 1949.

- 5 Clara Porset, “El Centro Urbano Presidente Alemán y el espacio interior para vivir,” Arquitectura/ México 32 (October 1950): 117.

- 6 José Roberto Gallegos Téllez Rojo, La artesanía, un modelo social y tecnológico para los indígenas. Política y Cultura (Mexico City: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, 1999).

- 7 Mariano Picón-Salas, “Vivienda para muchos,” Arquitectura/México 31 (May 1950): 56.

- 8 Porset, “El Centro Urbano ‘Presidente Alemán’”.

- 9 Clara Porset, “Diseño viviente. Hacia una expresión propia en el mueble,” Espacios. Revista integral de arquitectura y artes plásticas 16 (March 1953).

- 10 Graciela de Garay Arellano, Modernidad Habitada (Mexico City: Instituto Mora, 2004).

- 11 Anahí Ballent, “La publicidad de los ámbitos de la vida privada. Representaciones de la modernización del hogar en la prensa de los años cuarenta y cincuenta,” México Alteridades 6, no. 11 (1996): 53-74.

- 12 Pierre Bourdieu, La distinción. Criterios y bases sociales del gusto (Madrid: Taurus, 1988).

- 13 De Garay, Modernidad Habitada, 108.

- 14 Porset, “Diseño viviente”.

- 15 Porset, “El Centro Urbano ‘Presidente Alemán’”.

- 16 Porset, “Diseño viviente”.

Clara Porset’s Vision for Modern Mexican Housing

* Paper

+ Juan José Kochen (co-author)

¤ Clara Porset Dumas. Reflexiones sobre el diseño contemporáneo latinoamericano

¬ Rufino Tamayo Museum

^ Center for Industrial Design Research (CIDI)

∞ September 2018

Reviews:

Revista ASINEA

La Jornada

UNAM Global

Purchase book

Casa Bosques

Libros UNAM

El Péndulo

El Sótano