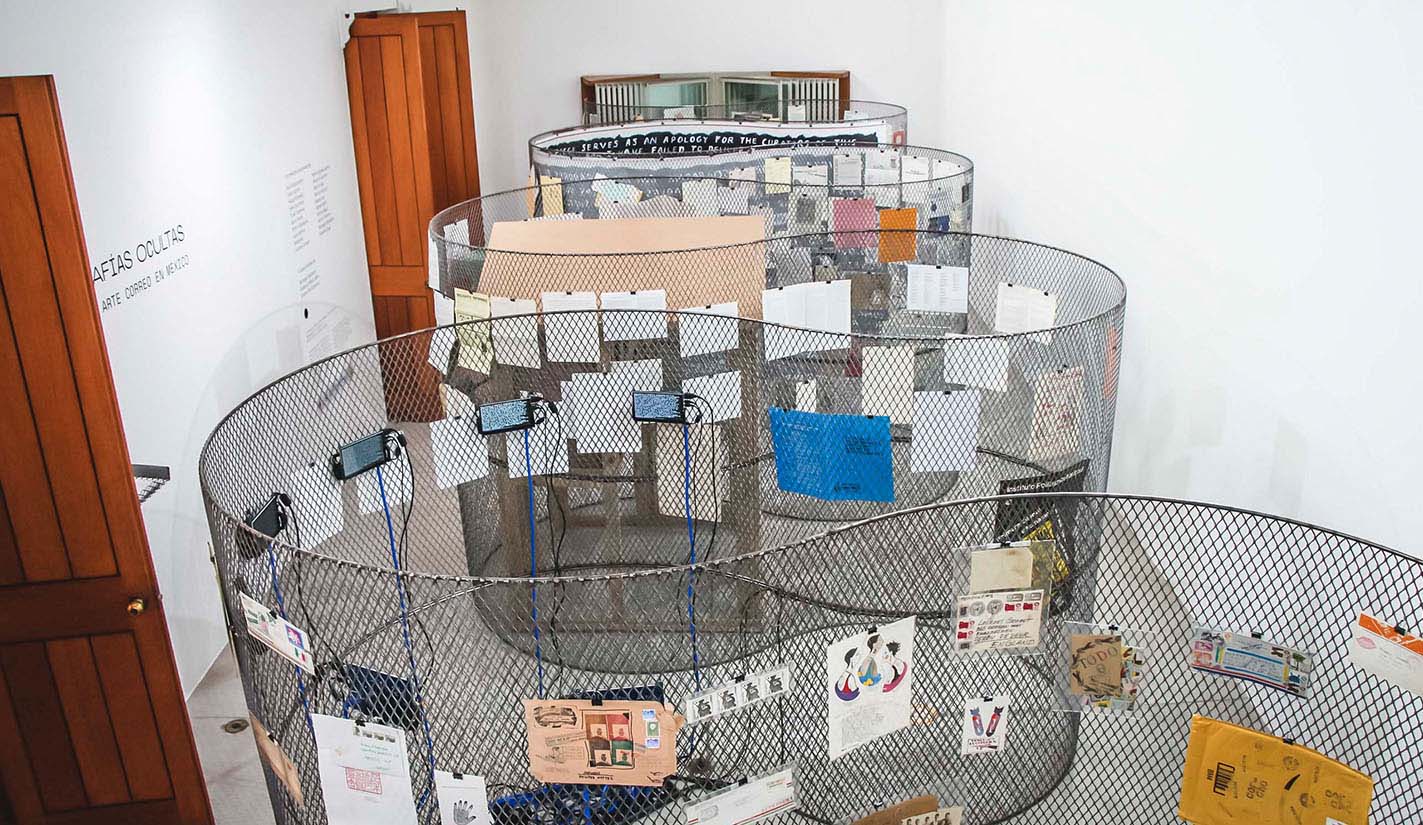

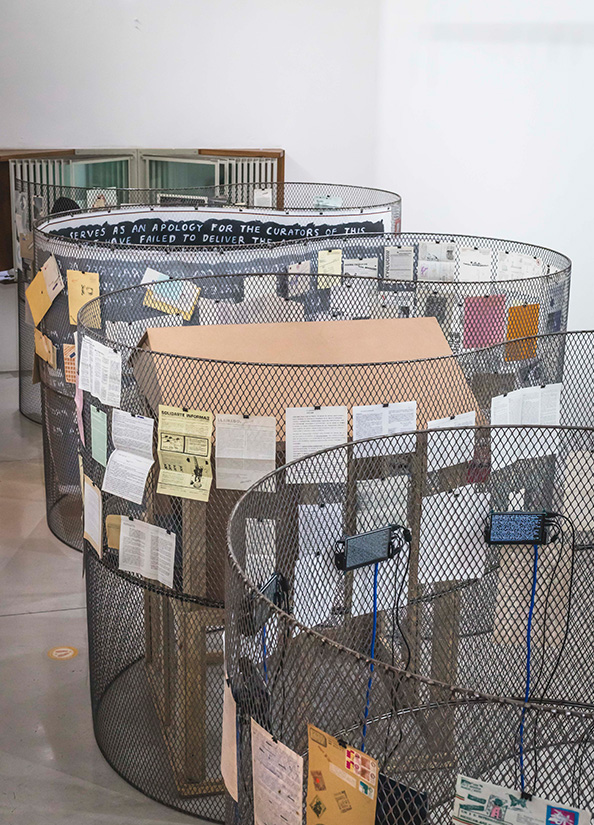

During the 1970s and 1980s, through the use of the postal system, mail art figured as a network of aesthetic-political exchanges between artists and collectives from different parts of the world. Based on archival material and contemporary re-examinations, Hidden Cartographies: Mail Art Circuits in Mexico seeks to show the infrastructures that allowed the construction and inscription of Mexican artists, collectives and groups in this global network, as well as the aesthetic and political concerns that motivated it. The exhibition makes visible the construction and use of the mail art network from four curatorial cores that lead us from the appropriation of the infrastructure of the postal system (envelopes, stamps, stamps) to the composition of the groups (directories) and the consolidation of their theory on mail art (manifestos, surveys, debates), passing through the transmission of news and updates, through periodic bulletins, and the different forms of collaboration that were established in the collective activities of mail art. Contemporary interventions, meanwhile, suggest links between past and present, mail art and current explorations.

1/

Dear Someone:

When we started digging through the mail art archives, a question arose that has stayed with us until today when we show you some of the dusted materials. Where to begin to excavate an international mail art network that by the 1970s and 1980s – its peak – had multiple entry and exit points, and which had no directing center but a series of scattered nodes. Giving another face to a globalization predominantly organized from the markets, mail art established a dynamic system of artistic interconnectivity that was nourished by shipments coming from geographic and ideological territories both close and very foreign to each other. In a short time, diverse aesthetic-political concerns traveled through local, regional and global circuits. Margaret Randall, then editor of the bilingual poetry journal El Corno Emplumado/ The Plumed Horn, described this network as “a world within a world, with no geographical borders, no entry requirements”.1

Behind mail art’s efforts to reconfigure cultural boundaries was its members’ rejection of the conventional models of production, circulation and promotion that characterized the global art market. It is clear that, in the early 1970s, the Mexican art field was ready to open up to these explorations. On the one hand, since the middle of the century, publications of international scope had emerged in Mexico, establishing links with allies such as the Brazilian Noigandres group. On the other hand, the experience of 1968 motivated the younger members of the artistic sector to organize themselves into autonomous “groups” or collectives. The same spirit of dissidence motivated them to seek languages that would allow them to act politically, aligning themselves with colleagues in Latin America who used conceptual art to confront military regimes and political repression. In this framework, mail art operated as that material network that connected them all, an independent circuit, created and managed by the participants themselves, which allowed for multiple forms of association. Espinosa, Zúñiga and Ocharán (all participants) say that mail art was for them “a system of distribution and circulation of artistic messages”.2 Through mail art, artists could test political ideas and exchange experiments in marginal media (the postcard, photocopy, fanzine).3 They could also test collaborative pieces that challenged the logics of authorship and individual prestige, preferring instead to copy, reproduce or drift. Meanwhile, sending by way of correspondence or gift proposed a way of exchanging art that turned its inscription in the market upside down. These exercises broadened artistic horizons and were key in the propagation of conceptual practices such as performance, the artist’s book or visual poetry.

The pieces that were exhibited in fairs, biennials, ephemeral events and other shows constitute only a fraction -minimal, we would say- of the aesthetic and political proposal of mail art. Mail art required collective coordination, a collaborative spirit and a strong desire for experimentation and rupture. That is why Ulises Carrion insisted that, from this point on, the organization and distribution strategy of each piece was not a merely circumstantial fact, but a formal element that constituted the piece itself.4 The regional, transnational and intercontinental trajectories built by mail art should be understood as part of its conceptual bet. Thus, when investigating the Mexican segment of the network, we have asked ourselves how to make a critical cartography of mail art that can be used to imagine new routes of research and artistic praxis. That is why, following Brian Larkin, for whom an infrastructure is “a matter that allows the movement of another matter”,5 in this exhibition we have sought to unearth the scaffolding of that infrastructure called mail art, both in its material and discursive dimensions.

Hidden Cartographies aims to show that many of the quests behind the design and use of the mail art network are anything but obsolete in the current context. Therefore, the excavation of its circuits implies tracing those hidden cables that lead from the past to the present and from the present to the past, showing the evolution and relevance of some of the initial concerns of mail art. In this sense, together with the archive, the exhibition includes contemporary interventions that make evident the resonances of mail art with our present reality, clues that in turn begin to trace paths towards the future. In the universe of cartographic practices, we agree with the geologist when she says that the keys to the past are inscribed in the present. But we also agree with the archivist who dusts off the past to understand the present. And also with the science fiction writer who, standing somewhere in the present, cannot help but observe in it the scattered signs of the future.

With love,

Someone else

1/

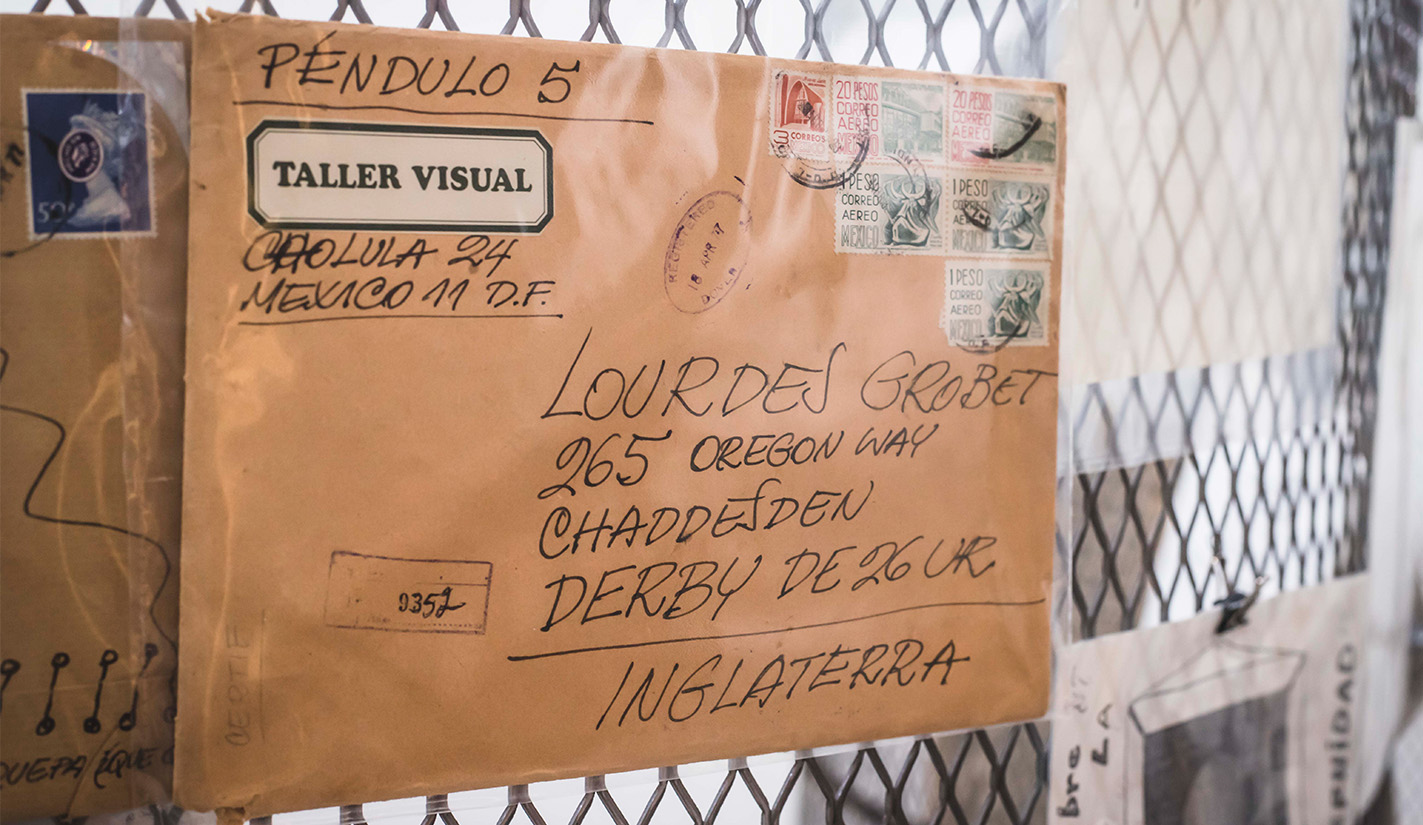

1. In the beginning was appropriation. There were scattered efforts in Latin America, the United States and Europe to mount an international mail art network on top of the infrastructure of the postal system, like an organism slowly growing inside another, using its organs, channels, nutrients and metabolisms. The result was a network of artistic communication that operated almost clandestinely through the postal infrastructure. Aware of this, artists celebrated this tactical appropriation through what Craig J. Saper once called “intimate bureaucracies.” If mailing was the point of mail art, everything that made it possible and that left traces of its displacement in time and space could be considered a core part of the work. The envelopes were more than envelopes, the stamps played with port marks, the stamps represented miniature experiments. According to Saper, these “intimate bureaucracies” functioned as nods of recognition between artists, a sign that sender and receiver were part of that deterritorialized community called mail art.6

2. Aware that the participants themselves were creators, managers and administrators of a network of horizontal artistic communication, they soon had to take a step back and ask themselves how they had gotten there and what that thing they called mail art consisted of. Did it mean the same thing in the Brazilian dictatorship as it did in France or England, behind or in front of the Iron Curtain? Inspired by cybernetic feedback, artists exchanged manifestos, ideas and theories that offered divergent explanations of the origin, objectives and scope of the mail art network. Ray Johnson’s “Correspondence School”, Fluxus’ “Eternal Network” or the Latin American concrete poetry circuits were all possible starting points, “alternative genealogies “7 for a network that in truth had multiple simultaneous origins.

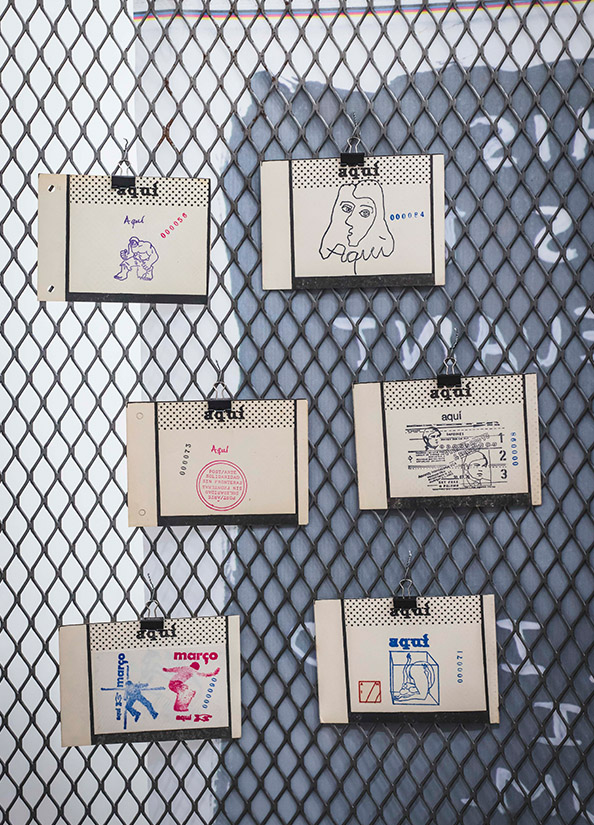

It was also said that some of the members of these groups (Felipe Ehrenberg, for example) established the first links with the mail art network and began to filter directories and calls for proposals. Little by little, as they joined, many of the “groups” became nodes of a network that allowed them to open local, regional and global lines of communication. Collectives such as Aquí or Colectivo-3 (later Post/Arte) emerged, dedicated specifically to mail art. Manifestos and theories of their own were written. Efforts appeared to establish formal associations at the local and regional level. At the same time, communication circuits multiplied among artists with similar political or conceptual concerns (performance, artist’s book, visual poetry), redrawing again and again the changing map of the international mail art network.

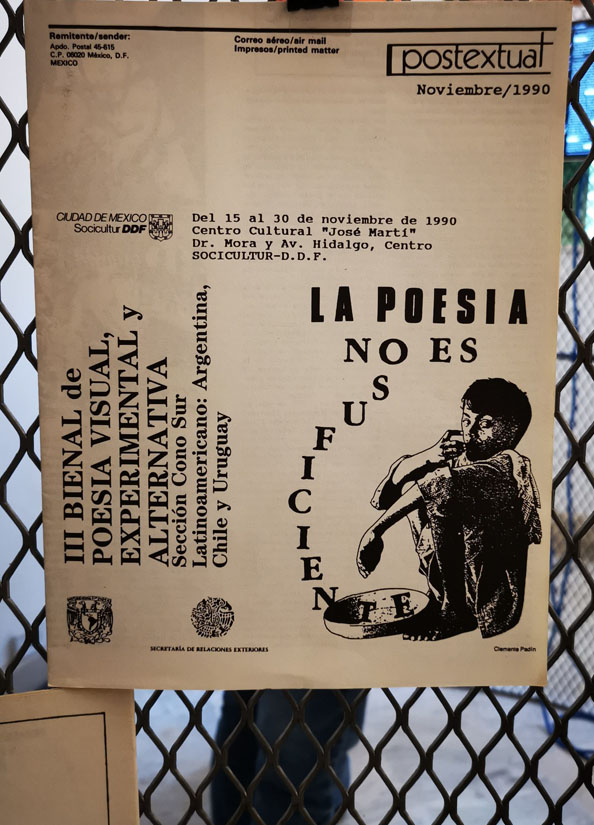

3. Since it operated outside art institutions, the mail art network had to be maintained, updated and expanded by the artists themselves. To this end, it was necessary to invent circulation and exhibition infrastructures that would allow the practice of mail art to become public. The artecorreístas were in charge of organizing different types of events, from collective exhibitions such as Salón Independiente to the International Biennials of Visual Poetry, seeking to draw a collective panorama of mail art that would show its heterogeneity and plural character. They also had to design and produce their own dissemination devices such as posters, invitations and catalogs.

To ensure the mobility of mail art and the continuous updating of the network, different groups organized periodic newsletters that followed the pattern of experimental mail poetry publications such as FILE, Schmuck or El Corno Emplumado. Araceli Zúñiga and César Espinosa’s newsletter Post/Arte not only circulated open calls and debates on mail art, but also issues specifically dedicated to visual poetry and other artistic expressions as they occurred in different countries. Manuel Marín’s group, on the other hand, circulated the mail art envelope-magazine Algo Pasa (in this case, they opted to reproduce all the materials in the issue, include a complete set of materials per envelope and send these envelopes to all interested parties). These publications made sure to keep the local nodes of the international mail art network active and updated.

4. The essential premise of mail art was to open routes for artistic collaboration through the postal system. For more than two decades, the circulation of invitations to participate in mail art events generated multidirectional exchanges. There were low-intensity nodes in mail art: occasional participants or sporadic collaborations. But there were also more stable nodes through which a greater flow of mail activity took place. Artists and organizing groups defined a variety of modalities of exchange, collaboration and collective creation. In its most intimate form, personal correspondence took place, experimenting with the encoding and decoding of postal messages. On other occasions, collective modalities of exchange were chosen through calls that established a theme and a form of participation: in these cases, the participations sent voluntarily from anywhere in the world were exhibited as part of the same collective piece. This is how events such as the Revolution Collective Poem, the series Put an Everyday Object Here or the collection of postcards Here were created. Regardless of the modality, feedback was the main ingredient of the mail art network, an oxygenating element that could take various forms: responding, intervening, quoting, forwarding. Each of these actions conceptually defined the material act of mailing. In the end, mail art became a language in itself, a system of codes that any participant could employ to establish different types of correspondence with peers around the world.

1/

Critical Overview

It was some of the artists who participated in mail art who, once its peak in Mexico and Latin America had passed, began to build a critical memory around this practice, theorizing the importance of mail art as an aesthetic and political (we could even say: utopian) horizon for the generation of the “groups” of the 1970s and 1980s. In 1986, Mauricio Guerrero published his undergraduate thesis El arte correo en México (published as a book by UAM in 1990), in which he reconstructed in detail the mail art movement as it developed in Mexico. In their journalistic texts from the 1990s, compiled in the book La perra brava (2002), César Espinosa and Araceli Zúñiga of Colectivo-3 and PostArte also reflected on mail art in light of the development of Mexican art at the end of the 20th century, while artists like Magali Lara held dialogues with critics like María Minera about it in new media such as email (Del verbo estar, 2017). For its part, the Museo de la Filatelia de Oaxaca held an international postal activity in 1999 that brought together some of the original participants such as Felipe Ehrenberg and Clemente Padín. However, the first retrospective exhibition of mail art, curated by Mauricio Marcín, took place until 2009 at the Museum of Mexico City and in 2011 at the MUFI. This exhibition, later condensed in the book Arte Correo (RM 2010), presented some of the most important pieces related to Mexican circuits on the net: Solidarte, the Collective Poem Revolution or the work of Polvo de Gallina Negra, among other works. Meanwhile, exhibitions and academic research on the artistic processes in Mexico during the 70s and 80s, on the “groups” of the 70s (Salón Independiente, Março, No-Grupo) or on specific artists such as Ulises Carrión or Felipe Ehrenberg have also contributed to reconstruct the historical place of mail art in Mexico.

Contemporary Artworks

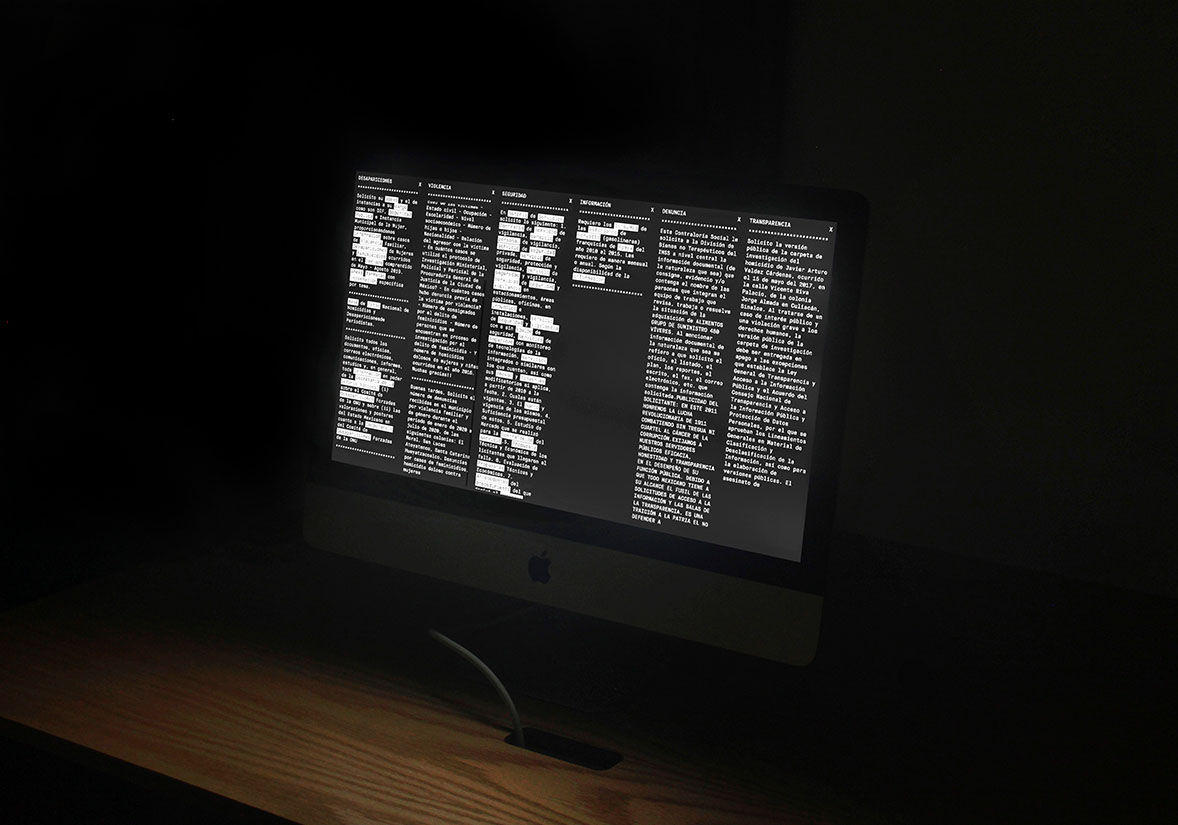

Mail art imagined intimate and horizontal channels of exchange that enabled the circulation of transparent information. Occupying the postal system, questioning its opacity, experimenting with its elements to challenge its mechanization and circumventing its censorship apparatuses made the participants of the network appropriate this infrastructure. La opacidad del silencio (multimedia installation, 2021) by Federico Pérez Villoro is part of a larger project that investigates the functioning of the Plataforma Nacional de Transparencia, a virtual system through which citizens can request information held by public administrations in Mexico. Through a program that acts on the interface, or occupies it, Pérez Villoro’s interactive piece detects, unearths and illuminates requests for information that were previously denied for containing classified information. A network of monitors randomly loads the results as the code advances. Thus, it verifies the (in)efficiency of access to information and offers a glimpse into the “memory of unanswered concerns”.

Since it was a network organized, maintained and governed by the artists themselves, mail art continually reflected on what was involved in sustaining a communication system, both in terms of material infrastructure and human organization and participation. Edwina Portocarrero’s Tweet (multimedia installation, 2021) asks similar questions in her investigation of the carrier pigeon network in Brooklyn, NY. Tracing the present of a residual communication system, Portocarrero reminds us that the origin of postal exchange lay in human-animal-technological assemblages (pigeons, horses, stamps, messengers), while reflecting on various organizational tensions within a communication network, if not clandestine, then marginal.

The artistic practice that developed within the mail art network allowed for diverse forms of collaboration: group works or collective activities, certainly, but also intimate exchanges and very personal ways of experimenting with the use of resources, languages and materials that traveled through the postal system. This led many of them to reflect on the failures of communication in the network, on the interference, noise or saturation that impeded the transmission of a message and made communication impossible. In a similar vein, Santiago Muédano’s El arte también se equivoca (El arte también se equivoca, 2021) asks about the cracks in a contemporary communication articulated in the virtual dimension of the networks. The very evolution of the piece at some point requested the intervention of the curators, who responded to the call to enter the conversation and correspond.

Public Program

Correspondences is a series of events where contemporary artists who collaborated in the exhibition will have the opportunity to activate their respective installations, as well as to share their creative processes. The series will give the opportunity to show the conversation between the two sides of the exhibition: the documentary archive and the contemporary installations, mail art in its heyday and current art, past and present.

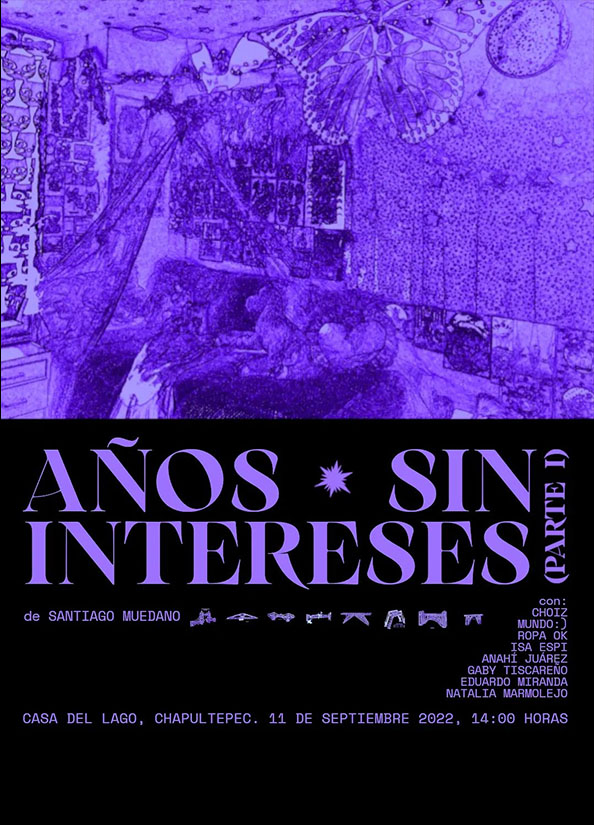

Years without interest (Part 1) with Santiago Muedano (MX)

Sunday, September 11| 14:00 | Espacio Sonoro (MX)

Our life extends beyond the crap that happens to us. This was a durational and sonorous performance in seven voices that honored that fact. It proved necessary to move on from self-cancellation and disbelief because ultimately we are still here. Like all art, this was a pretext to explore personal quests. There is a crossover between music and the visual arts, and Casa del Lago UNAM is one of the venues that understands it the most. Santiago Muedano took advantage of this condition to perform “molecular cuisine” but through a song. It was read and sung aloud to reach a connection. Long live the bridges and the years without interest (2020 – 2021).

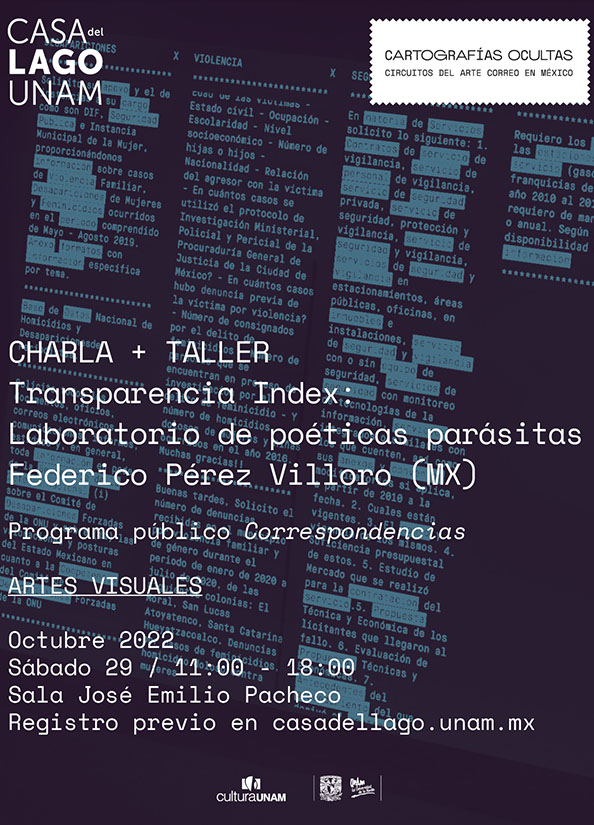

Transparency Index: Laboratory of parasitic poetics with Federico Pérez Villoro (MX)

Saturday, October 29 | 11:00 – 18:00 | José Emilio Pacheco Hall

This activity took as its starting point Transparencia Index, a project by Federico Pérez Villoro designed to automatically extract data from the National Transparency Platform, a system through which people can request public information from the Mexican government. The program identifies existing requests associated with topics of common interest that were previously denied for containing information classified by the authorities. This constant flow of unanswered civic concerns is displayed on an interactive website that seeks to record, through labyrinthine links, the bureaucratic opacity and strategic silence of the country’s administrative institutions. The people who participated in the Laboratory of Parasitic Poetics worked from the platform’s databases: an abundant repository of shared questions and an incomplete reflection of what has historically afflicted Mexican society. From a series of generative exercises, the group worked on the creation of a collective poem that was circulated as a request for information.

1/

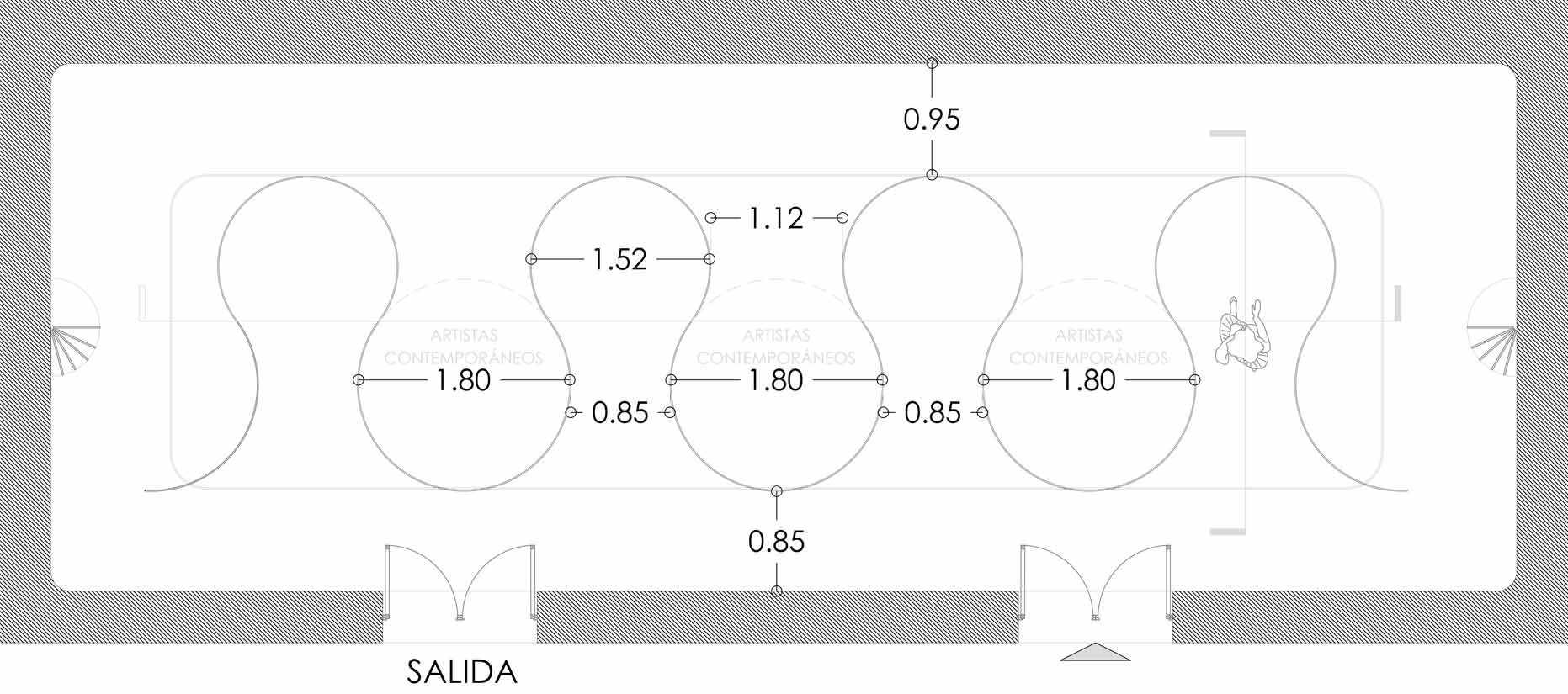

Exhibition design and graphic identity

Estudio Fi is an architectural practice in Mexico City. Its work addresses different scales and interests, from small-scale and museographic works to residential housing, cultural buildings and industrial works. In all cases, she recognizes in the process of design and construction a tool to move freely from our history and our context.

Jackie Crespo graduated in visual communication from Universidad Centro de Diseño Cine y Televisión in 2019. In 2017 she co-founded the art book publishing and printing company Can Can Press. Later, in 2021 she opened the contemporary art gallery Can Can Projects, located in Mexico City. Jackie is currently dedicated to

1/

Archives consulted and exhibited: César Espinosa and Araceli Zúñiga private collection, María Eugenia Guerra personal collection, Mauricio Guerrero archive, Mauricio Marcín archive, Felipe Ehrenberg collection, (Arkheia MUAC Collection), No Grupo collection, (Arkheia MUAC Collection), Alberto Híjar collection (Arkheia MUAC Collection), Marcos Kurtycz collection.

Acknowledgements: Lorena Botello, Natalia Brizuela, César Espinosa, Natalia de la Rosa, Ana García Kobeh, Daniel Garza Usabiaga, María Eugenia Guerra, Mauricio Guerrero, Martha Hellion, Alejandra Kurtycz, Magali Lara, Mauricio Marcín, Alejandra Moreno, Clemente Padín, Elva Peniche, Araceli Zúñiga and the team of the Museo de la Filatelia de Oaxaca.

Project carried out with the support of the Sistema de Apoyos a la Creación y Proyectos Culturales (FONCA).

Project sponsored by the Patronato de Arte Contemporáneo.

- 1 Randall, Margaret. “Carta a Arnaldo Orfila Reynal.” Margarett Randall Papers. Center for Suthwest Research, University of New Mexico.

- 2 Espinosa, César, Leticia Ocharán and Araceli Zúñiga. “México ¿Posmodernismo sin vanguardia?” In César Espinosa y Araceli Zúñiga, La perra brava: arte, crisis y políticas culturales. Mexico: UNAM/STUNAM, 2002: 119-131.

- 3 Marcín, Mauricio. “Arte correo en un libro.” En Mauricio Marcín (editor), Arte Correo. Barcelona: RM, 2011.

- 4 Yépez, Heriberto. “La poética de Ulises Carrión.” In Ulises Carrión, Montones de metáforas. Mexico: Malpaís, 2019.

- 5 Larkin, Brian. “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure,” Annual Review of Anthropology 42 (2013): 27-43.

- 6 Saper, Craig J. Networked Art. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

- 7 Gilbert, Zanna. “Genealogical Diversions: Experimental Poetry Networks, Mail Art and Conceptualisms,” caiana 4 (2014): 1-14.

Hidden Cartographies: Mail Art Circuits in Mexico

* Exhibition

+ Co-curated by:

Alfonso Fierro

Featuring artworks by:

Federico Pérez Villoro

Edwina Portocarrero

Santiago Muedano

With archival material from:

Maris Bustamante, Ulises Carrión, Felipe Ehrenberg, Helen Escobedo, César Espinosa, Aarón Flores, Pedro Friedeberg, Jesús Romeo Galdámez, Lourdes Grobet, María Eugenia Guerra, Mauricio Guerrero, Alberto Híjar, Marcos Kurtycz, Manuel Marín, Mónica Mayer, Leticia Ocharán, Santiago Rebolledo, Araceli Zúñiga

Exhibition design:

estudio fi

Graphic identity:

Jackie Crespo

¬ Casa del Lago

Museo de la Filatelia de Oaxaca

∞ August 2022 – January 2023

September 2021- January 2022

Featured on:

Fundación Harp Helú

Stay Happening

Milenio

Once Noticias

Terremoto