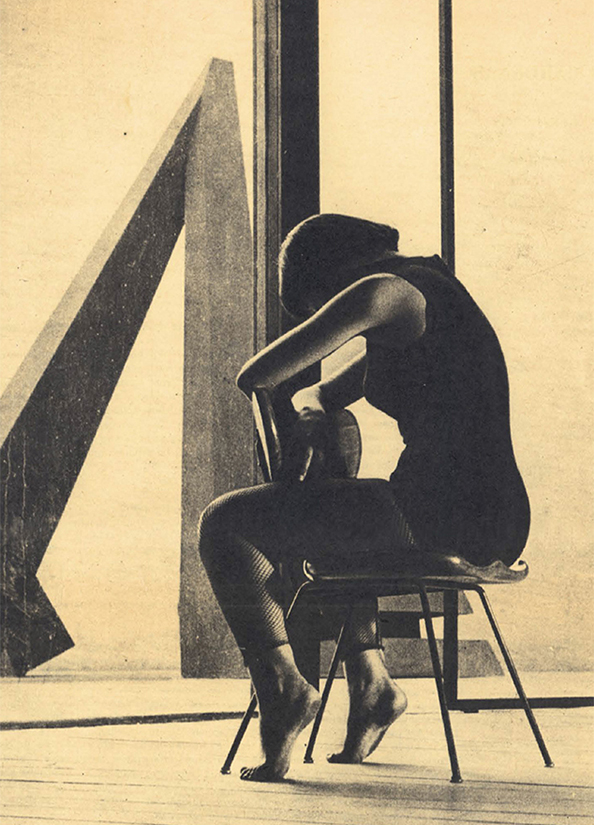

El Eco had not yet opened its doors when Mathias Goeritz invited Pilar Pellicer to participate as a model in a photo shoot that would serve as a showcase for his new project.11 Pilar Pellicer tells in an interview with Paola Santoscoy that in the Eco “nothing had happened yet” when the session was held and that the photos were to advertise the Eco. See: http://eleco.unam.mx/eleco/ interview-with-pilar-pellicer-by-paola-santoscoy/ When presenting at the venue, Pilar posed at the foot of a sculpture designed by the artist – ‘ El Torso’- and improvised a series of movements around a group of chairs that had some formal similarities with the previous piece. The chairs, all apparently identical, consisted of a voluptuous wooden back and seat joined by two metal bars and supported by four slightly open legs. Its uniqueness within the building lay in its proportions which on the one hand obeyed a human scale that accompanied the figure and body expression of Pilar and on the other, they contrasted with the monumentality of the space. The photographs were published in local and international media; The young aspiring dancer appeared in different positions within the museum, usually alone, but at times accompanied by Goeritz.

Decades later, the session would become one of the emblems of El Eco that would remain engraved in the popular imagination along with the ideographic drawing for El Eco that Goeritz made in 1951 after the commission made by Daniel Mont. The patron had seen Goeritz’s resistance to obeying the conventions of architecture, the potential to build something unprecedented, and asked him for a project in which he would do ‘whatever he wanted’.22 “Emotional Architecture?”, in Architecture, Mexico, no. 8-9, May-June 1960, pp. 17-22. The drawing was a kind of cubist perspective loaded with geometric expressions represented by thin and thick lines, where elements located at strategic points were outlined. At first glance they highlighted a perspective corridor –which ended with ‘El Torso’- and a cross window that overlooked a patio with the sculpture that was later known as ‘ The Serpent’ .

The ideogram reflected intuitive language that came from emotional impulses rather than logical design decisions. Goeritz later commented in relation to the museum that it “began its experiments, with the architectural work of its own building”.33 Miranda, David. The Dissonance Of The Echo. 1st edition. p. 26. The construction of the museum, in fact, was based on this premise and in the absence of a traditional architectural project, the construction of El Eco required Goeritz’s comprehensive supervision, so the artist moved from Guadalajara to Mexico City in the summer of 1952 in order to size your vision ‘ on site’. Daniel Mont was his cufflink during this process and both Ruth Rivera Marín and Luis Barragán intervened in the project as advisors, playing a fundamental role in determining which pieces could compose the space to achieve the plastic integration or ‘Gesamtkunstwerk ‘44 Gesamtkunstwerk refers to the synthesis of various artistic expressions in one piece. that would give it meaning to El Eco.

With a few months to complete the museum, Goeritz began to produce the material of his authorship that would be part of the museum and commissioned a series of works of art to figures of the international avant-garde and dissenters from muralism. While some would be concluded before the inauguration, others would be part of an ambitious contribution agenda to be developed in the coming years. These contingent interventions focused the attention on multiple journalistic articles that anticipated the opening of the Experimental Museum, among them, the mural that Henry Moore made for El Eco –and that he did not get to paint–, a grisaille of about one hundred square meters that Rufino Tamayo had sketched and Goeritz’s ‘The Serpent’; chairs, on the other hand, were never mentioned.

1/

After the opening of El Eco, in September 1953, some members of the hegemonic faction of artists of the Mexican School of Painting took the opportunity to publicly speak out against Goeritz. The rejection responded to the provocation represented by the German artist’s work to the Mexican plastic tradition which was based on creating social awareness of the Mexican identity through paintings of already established techniques and formats. In El Eco, it was clear how Goeritz transcended regional limits by taking his work to a phenomenological level – lacking identity associations – and disciplinary limits when alternating between different roles: artist, sculptor, architect, builder and designer.

These ideological tensions influenced the transience that would mark El Eco, although the main factor that caused the Experimental Museum to close almost as soon as it opened was the sudden death of Daniel Mont in October 1953. Without the figure that allowed this radical initiative to be possible, the project that aspired to become so many things, was surrounded by unknowns and to a certain extent, it was left unfinished, or rather, El Eco never was.

The doors of the building were not reopened until a year later when it was acquired to be transformed into a restaurant / bar. The name was preserved –Restaurant El Eco– and the original pieces that were once presented in the museum were reused (this time arranged arbitrarily), however, the conception around the project was gradually deformed. In June 1955, the newspaper ‘ Amav News ‘ which published a photo with the chairs in the entrance hall along with ‘ El Torso’, wrongly mentioned that Henry Moore had been the original creator of the museum and omitted the name of Goeritz [ 5]. El Eco Restaurant was just the beginning of an erratic journey that the building would follow in the course of the following years. In essence, the property was passed from owner to owner, and each one conditioned it according to their interests: when it was a restaurant, they added a canopy to the facade, when it became the University Theater Center, they closed the patio with a latticework and When it was taken by the Free Center for Theatrical and Artistic Expression (CLETA), they painted it blue and gold and covered it with banners announcing different events.

In the midst of these programmatic transformations, each of the elements that Goeritz had conceived to inhabit El Eco was dissipating. The artist once related how the famous ‘ Serpent’ that was originally in the courtyard was divided into parts and sold to an individual to later be rearmed on his property [6] . He adds that he was never interested in looking for it since from the beginning he did not design sculpture as an independent work of art but as part of a whole special atmosphere that gave meaning to El Eco [7] .

In 2000, the building threatened to be demolished to make way for a parking lot. By mid 2004, UNAM acquired the property and entered a recovery phase. The physical reconstruction of the building was not the only challenge but also to revive the memory of Goeritz himself, who by then was already an artist with little exposure in the contemporary cultural sphere. Almost as the first stone, Felipe Leal, who in addition to managing the restoration, directed the Faculty of Architecture, maintained after the reactivation announcement, that El Eco was together with the Casa Luis Barragán and the Casa Estudio of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, one of the three key pieces of modern architecture in Mexico [8] .

As a reverse trip, the team in charge stated that they were coordinating the return to the venue of the pieces that had been made for the museum [9]. To the surprise of the attendees, almost none of them were present at the reopening and, in return, in the “Daniel Mont” room located on the first floor, a sample curated by Guillermo Santamarina around the history of El Eco was made. Rather, fragments of what existed in the museum were presented, mostly in the form of documents: references to the Goeritz snake, books, enlarged reproductions of the mural that Rufino Tamayo did not make due to lack of resources, notes left by Henry Moore and photographs. As for the chairs, a reproduction of one of the photographs of Pilar Pellicer dressed as a ballerina was exhibited next to a chair whose identity card was titled ‘ Silla para El Eco’ [10]with Daniel Mont and Mathias Goeritz as authors. The specimen had ostensible changes in relation to the photographed chair – let’s call it Dance Chair to differentiate it from this new one; the structure was a single piece that folded on its axis and supported the seat at two points, in addition, in the upper part of the backrest there was a perforation.

The chair was part of an 8-piece dining room that was in the Mont house in Cuernavaca and was a loan made by Catalina Mont –daughter of Daniel– to Santamarina, director of the museum at the time. Catalina was a few months old when Daniel Mont died and therefore, she never witnessed the Dining Room Chair – let’s call it that – inside the museum, rather she remembers the whole as pieces of furniture that were part of her childhood; However, testimonies from her grandparents who said that the chairs were part of the bar, would lead her to deduce that the chairs had been transferred from the museum to her family’s home.

Even without conclusive evidence that the chair belonged to the museum, some formal qualities of the Dining Room Chair referred to some elements of the museum. The zigzagging that forms the structure alludes to the broken angles of the serpent and both, when facing the smooth walls of the museum, gave an accent of movement that was cadentially related to the space. Added to this, the anthropomorphic texture of the back and the seat – very similar to those of the Silla Danza – contrasted with the rigid angles of the El Eco building.

The set had variations that presuppose that it was the result of a succession of tests. Even the Dining Chair could have been a predecessor to the set of chairs that were used for the Pellicer photo shoot and in reality the Dance Chair would have responded to the need to manufacture a simpler structure that would allow the chairs to be produced in series. In this sense, the way in which the Dining Chair was made as a set of unrepeatable pieces that had to be manufactured individually, would be closer to the production model under which El Eco was born, specifically reflected in the ideogram that Goeritz made for the project and in which he positioned himself against a unified image that was easily reproducible.

Despite the growing interest around Goeritz that was generated once El Eco reopened and the fixation on the chair justified in being one of the few manifestations of the artist as a designer, the ‘ Chair for El Eco’ that was presented in that exhibition did not It would be exhibited again in the future. Guillermo Santamarina tells how on one occasion the museum staff came across the room without the Dining Chair . The strange theft would be followed by a sudden return that would be accompanied by a note. The text read that a worker close to Goeritz who wanted to spend his last days by the chair asked to be brought to him. In the face of the incident, the Mont sisters refused to re-loan any of the copies they owned.

Despite this, the chair continued to circulate but this time in the form of reissues. In 2007 Emiliano Godoy and Jimena Acosta curated ‘ Cajas de Transit’ , a traveling exhibition that brought together 23 paradigmatic chairs from the second half of the 20th century made by architects, designers and artists. Since the dining chair that curators had seen earlier in the exhibition Eco would not be borrowed, he was commissioned Bernardo Gómez Pimienta and Juan Zouian a reproduction of it. When facing the set of chairs by Catalina Mont, they chose to make a synthesis of the variations and an interpretation of what, from their approach, would have been the model of the chair that Goeritz and Mont would have wanted to make from the prototypes they produced .

His reading of what the ‘ Chair for El Eco’ would have sought to be, was consistent with an Eco that had never been consolidated. In addition to perceiving differences in textures, proportions and shapes, they found some chairs that did not have the perforation that existed in the one exhibited and others whose metal structure differed from the Dining Room Chair , some in which the finish was It was closer to a silver-colored chrome metal and others without a support frame on the seat. Based on these observations, they made design decisions that led them to produce the Transit Chair .

The exhibition traveled throughout North America and Europe, becoming a benchmark for exhibitions focused on contemporary Mexican design. In 2011, prior to ‘ Happiness is a hot and cold sponge ‘, which was also curated by Guillermo Santamarina, Archivo Diseño y Arquitectura managed his own reproduction of the ‘ Chair for El Eco’ .

In recent years, the chairs have been disseminated through various publications and exhibitions, sometimes with inaccuracies and others with technical details and data that separate them from each other, but always bearing the same label: the title of ‘ Silla para El Eco’ . This locution contains a multiplicity of meanings. The obvious association would be that what makes the ‘Chair …’ be ‘… for El Eco’ is the characteristic of having inhabited El Eco and under that premise, it could be said that the Dance Chair it is the only one that could undoubtedly carry that title. However, it is useless to reduce the title to that condition if we consider that the ‘for’ in the chair for El Eco is not necessarily limited to a spatial or place relationship and therefore, a ‘Chair for El Eco’ should not have existed within El Eco.

Taking into account the uses of the preposition ‘for’, the one that refers to purpose stands out – and is appropriate in this case. Let’s think that the ‘Chair for El Eco’ could be the one whose initial purpose was to belong to the site. In this sense, all the versions analyzed here could be the ‘Chair for El Eco’, as they have formal characteristics similar to the volume of some of the museum’s works and in communion with the tectonics of the building. In this sense, there would be no need to have spatially occupied El Eco, even the multiple essays that surround the Dining Room Chair could fulfill the function of belonging to El Eco only by approaching the plastic objective of the museum.

It would also be worth rethinking the meaning of El Eco and going over its representations. The imaginary of El Eco today goes beyond the temporal and physical limits of what was the –finite– event of 1953. By linking the idea of the Experimental Museum to what it transformed when it was closed, the multiple concepts that are evident it absorbed Goeritz’s project and derived from its own genesis. In a similar way to the chairs, the building became over and over again something that would challenge its original aspirations, transmuting according to who occupied it and their interpretation of the function it supposed to fulfill. Likewise, when circulating on certain platforms and in specific contexts, El Eco left its mark, without having to have a material backing, and gained momentum that made it one of the insignia of Goeritz.Each of these chairs, therefore, acquires a unique value by being linked to this phase of the artist’s work and, in turn, unites the body of ideas that supports El Eco ecosystem. In this way, the chairs and the Museum Experimentally they enter into a reciprocal game of significance.

Finally, if Mathias Goeritz sought to renounce conventional architectural representations due to their substitute power and the passivity that this caused in its spectators, the set of chairs analyzed here becomes a product of that vocation by actively involving the user in a comparative exercise in around the ‘ Chair (s) for El Eco’ or even by pushing it to question whether it makes sense to be an accomplice or opponent of the legitimacy of this title for any of the chairs that have been so named. The chairs, beyond their value as design pieces, carry with them a symbolic charge that makes them function as artifacts for reflection and discussion. The ‘Chair for El Eco’ is the story of El Eco, of its ethos and context, it is the mnemonic reconstruction of a disjointed record and subsequently the fabrication of a myth, it is a collection of five chairs interrelated and at the same time rooted in a landmark of architecture; the ‘ Chair for El Eco’ are all and there is none.

- 1 Pilar Pellicer tells in an interview with Paola Santoscoy that in the Eco "nothing had happened yet" when the session was held and that the photos were to advertise the Eco. See: http://eleco.unam.mx/eleco/ interview-with-pilar-pellicer-by-paola-santoscoy/

- 2 "Emotional Architecture?", in Architecture, Mexico, no. 8-9, May-June 1960, pp. 17-22.

- 3 Miranda, David. The Dissonance Of The Echo. 1st edition. p. 26.

- 4 Gesamtkunstwerk refers to the synthesis of various artistic expressions in one piece.

- 5 "El Eco", in Amav News, year 1, no. 8, June 25, 1955, p. 12.

- 6 Goeritz, Mathias. (1970). ‘The Sculpture ‘The Serpent Of El Eco’: A Primary Structure Of 1953’. En ‘Leonardo 3 (1): pp. 63-65’. Londres: Pergamon Press.

- 7 Ibid.

- 8 "UNAM Will Not Skimp On The Rescue Of El Eco". (2017). The universal. http://archivo.eluniversal.com.mx/ culture/35523.html

- 9 Ibid.

- 10 The chair was presented for the first time in 'The echoes of Mathias Goeritz', an exhibition whose curatorship was in charge of Ferruccio Asta and which was presented at the Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso until April 26, 1998.

The “chair”, the “for” and “El Eco”

(Español) * Texto de hoja de sala

¤ Archivo Abierto: Las sillas para El Eco

¬ Archivo Diseño y Arquitectura

∞ marzo 2017