“The Beast,” a colloquial term, refers to the freight trains utilized by Central American migrants in their journey to the United States through Mexico. To grasp its history, one must delve into two concurrent events: the mass exodus of Central Americans fleeing internal conflicts in their home countries, and the resurgence of Mexico’s previously fragmented rail system as a freight corridor from the southern border to the north. These intertwined realities led migrants to view the railway system as a potential route to the Mexico-United States border, with the moniker “The Beast” symbolizing the years of informal occupation of these infrastructure, where people traveled precariously in carriages not designed for passengers, risking their lives. For those familiar with the train’s impact on thousands of immigrants, it embodies a powerful yet menacing force.

These insights formed the foundation of a research project undertaken within the master’s program “Critical Conceptual and Curatorial Practices in Architecture” at Columbia University in New York, resulting in a thesis, exhibitions, and a seminar.

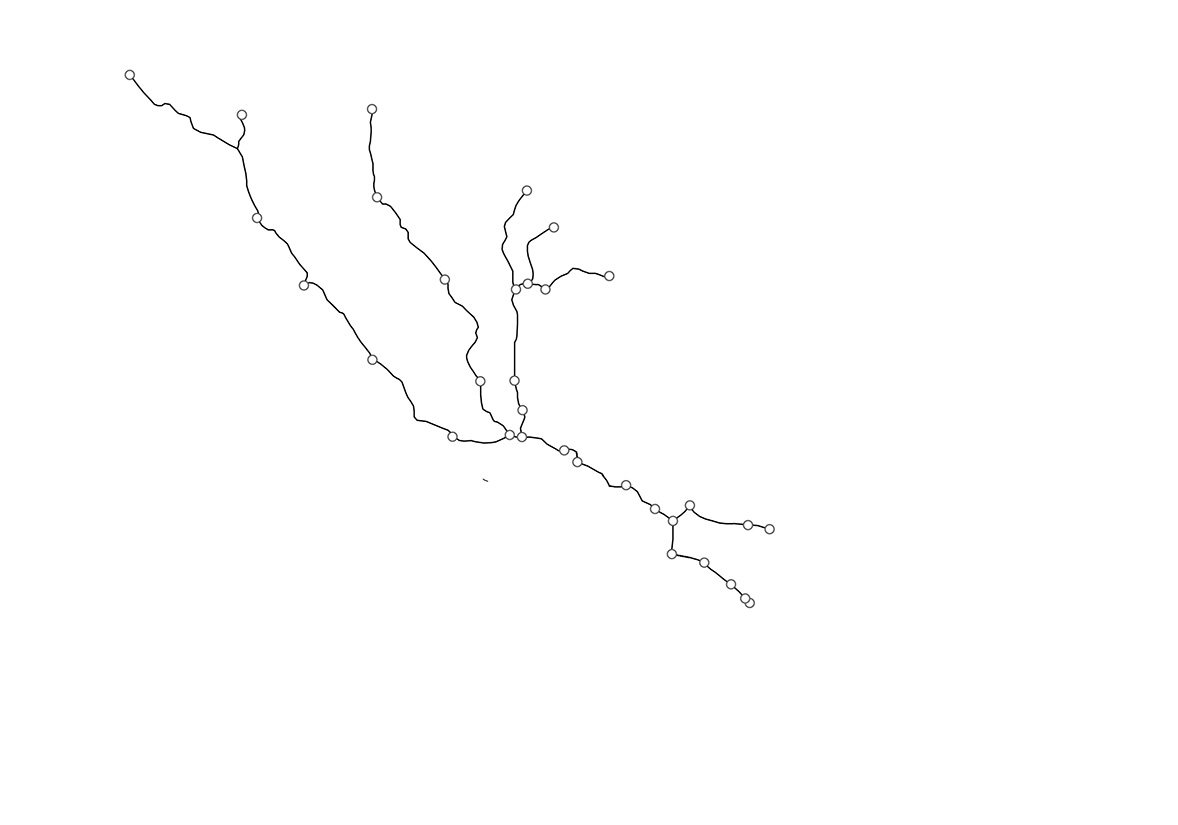

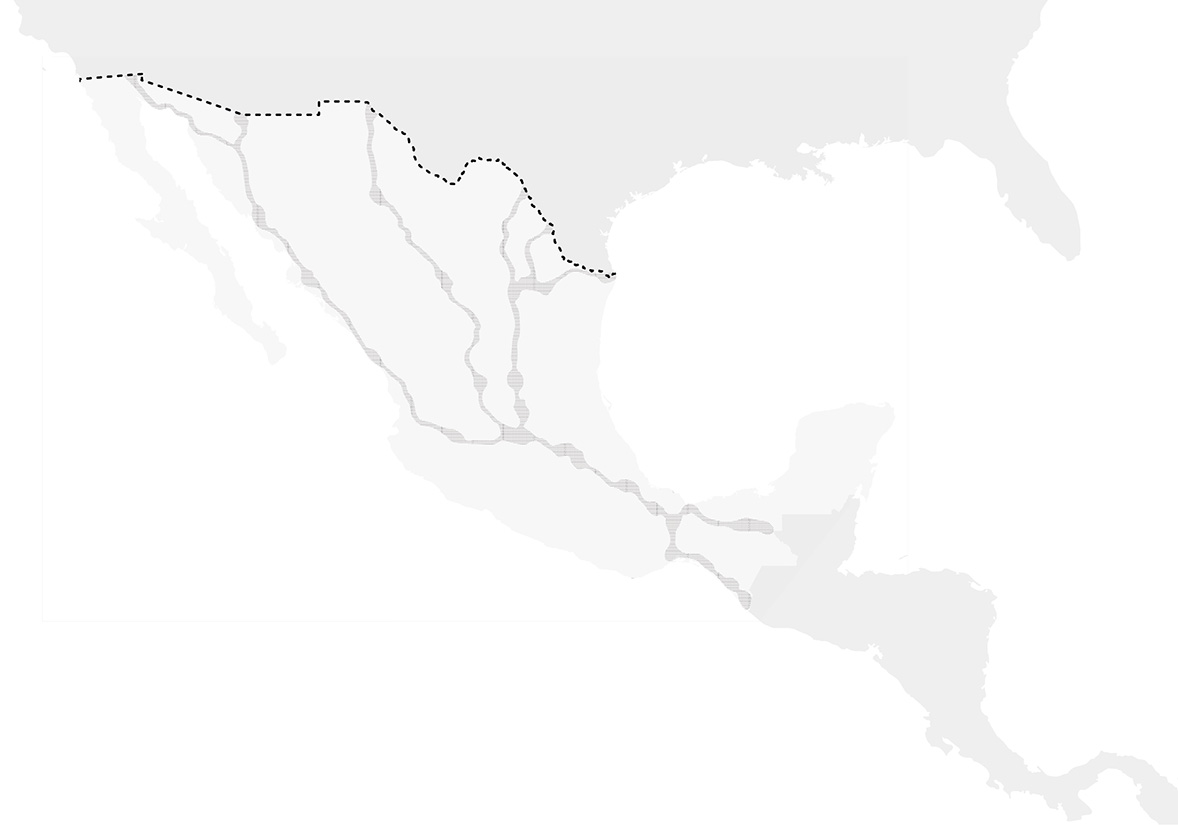

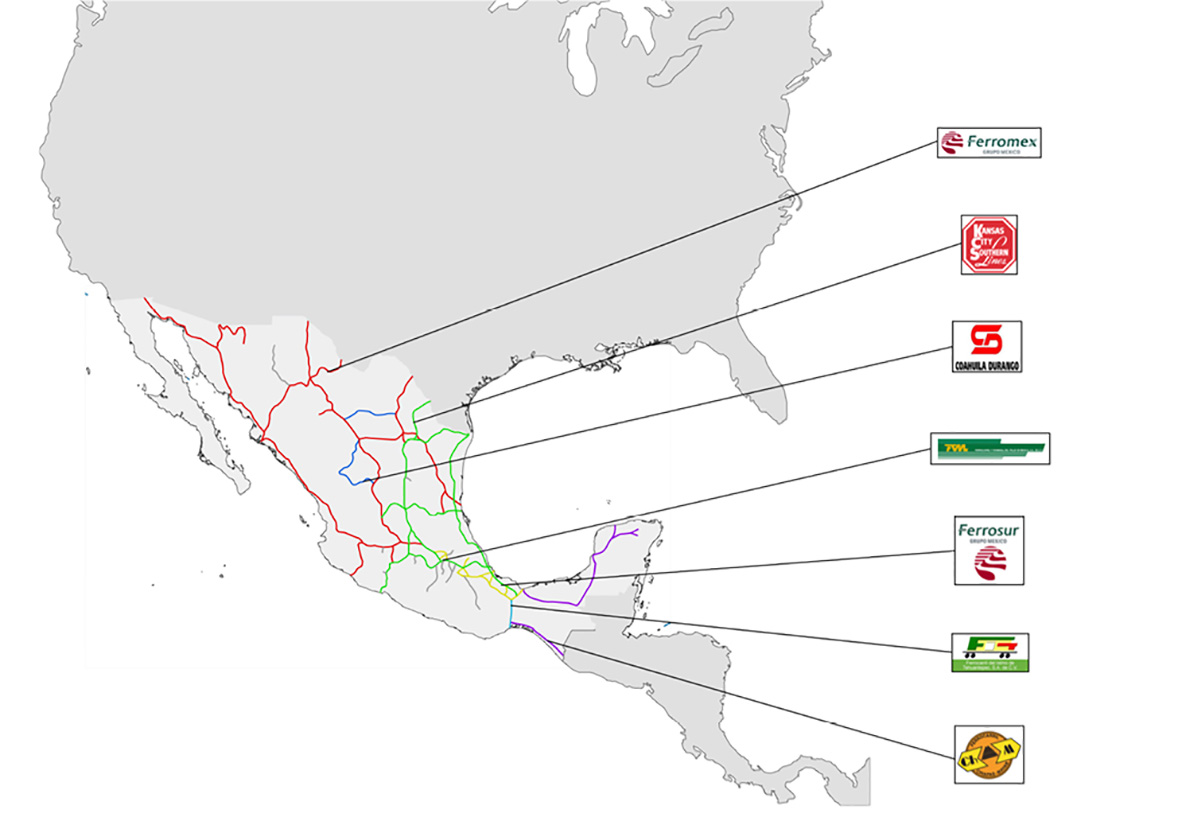

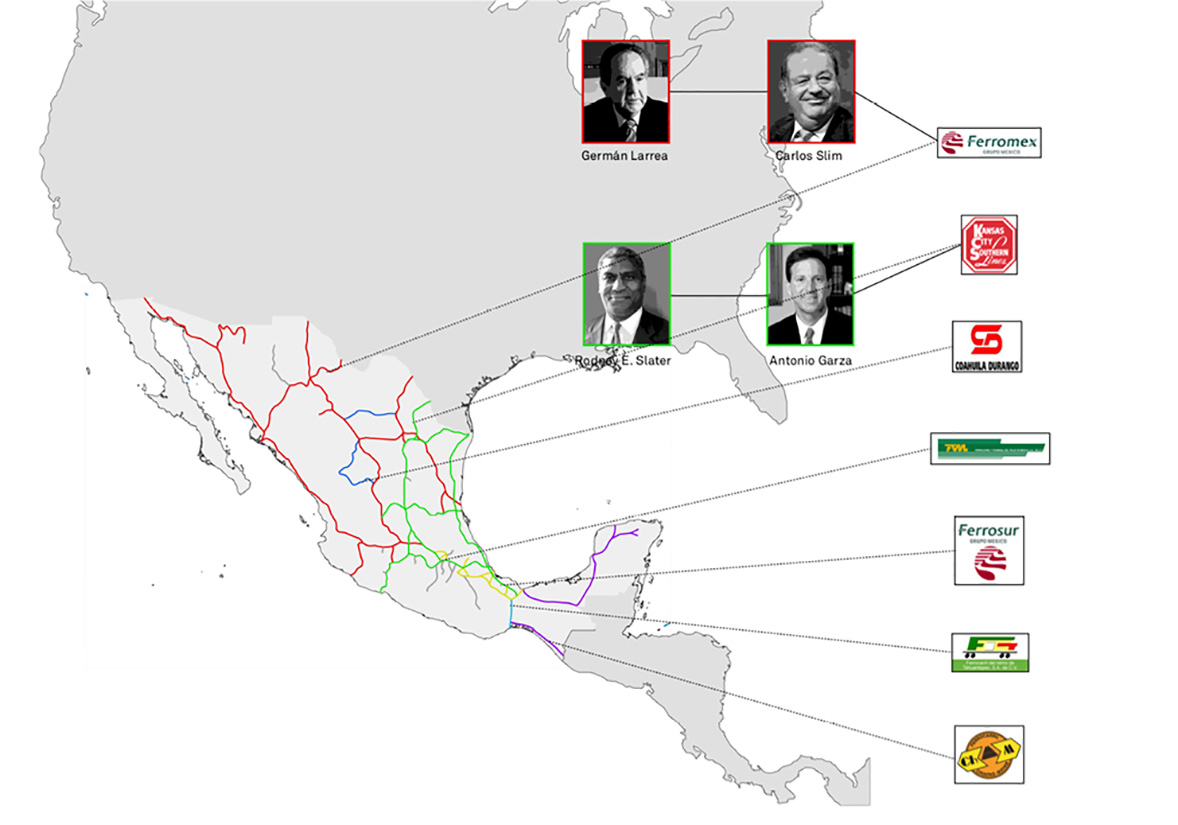

Mapping The Beast’s routes revealed that from the outset, migrating populations gravitated towards three main routes. These paths offered direct access to the northern border and lacked surveillance, enabling migrants to traverse the country discreetly. These factors are crucial in understanding what attracts and sustains The Beast’s networks.

Overlaying The Beast’s routes with the trade system between the United States and Mexico uncovered a fascinating coincidence: The Beast had essentially become integrated into the commercial system between both countries. Over two-thirds of the Mexican railway system had been utilized by Central American immigrants at some point. This commercial infrastructure accommodated both goods, which transformed into capital, and individuals who transitioned into labor upon crossing the border.

However, migrants’ routes were not as uniform as trade routes. Due to frequent stops (at least 15 during their journey), their experience extended beyond the train, with fragmented journeys of varying lengths.

As migrants traversed Mexico, occupying commercial spaces, new territories emerged beyond the trains. This notion formed the basis of my master’s thesis project, proposing that each train stop along La Bestia triggered new dynamics in nearby towns, ultimately leading to the evolution of new architectures and landscapes in constant flux.

With this hypothesis in mind, my aim was to translate the transition of territories prior to their transformation by The Beast into a representation that could illuminate the phenomenon and its implications. The primary challenge lay in articulating these reflections in a language accessible to a general audience, requiring not only objectivity but also sensitivity and understanding of a broader context.

1/

1/

At the year’s end, I made the decision to narrow my exploration route to the segment stretching from the Guatemala border to Mexico City. This decision stemmed from media reports and data from the National Migration Institute, which indicated that these states harbored the highest concentration of migrants. Beyond Mexico City, migrants tended to disperse to diverse areas rather than following a unified route.

In January 2015, I flew to Villahermosa, Tabasco, and then proceeded by bus to Tenosique, marking the commencement of my journey. Over the ensuing 13 days, I visited a series of towns, including Palenque, Tapachula, Ciudad Hidalgo, Huixtla, Arriaga, Juchitan, Ixtepec, Tierra Blanca, Córdoba, and La Patrona. Unfortunately, the Medias Aguas stop, originally planned between Ixtepec and Tierra Blanca, had to be excluded due to safety concerns.

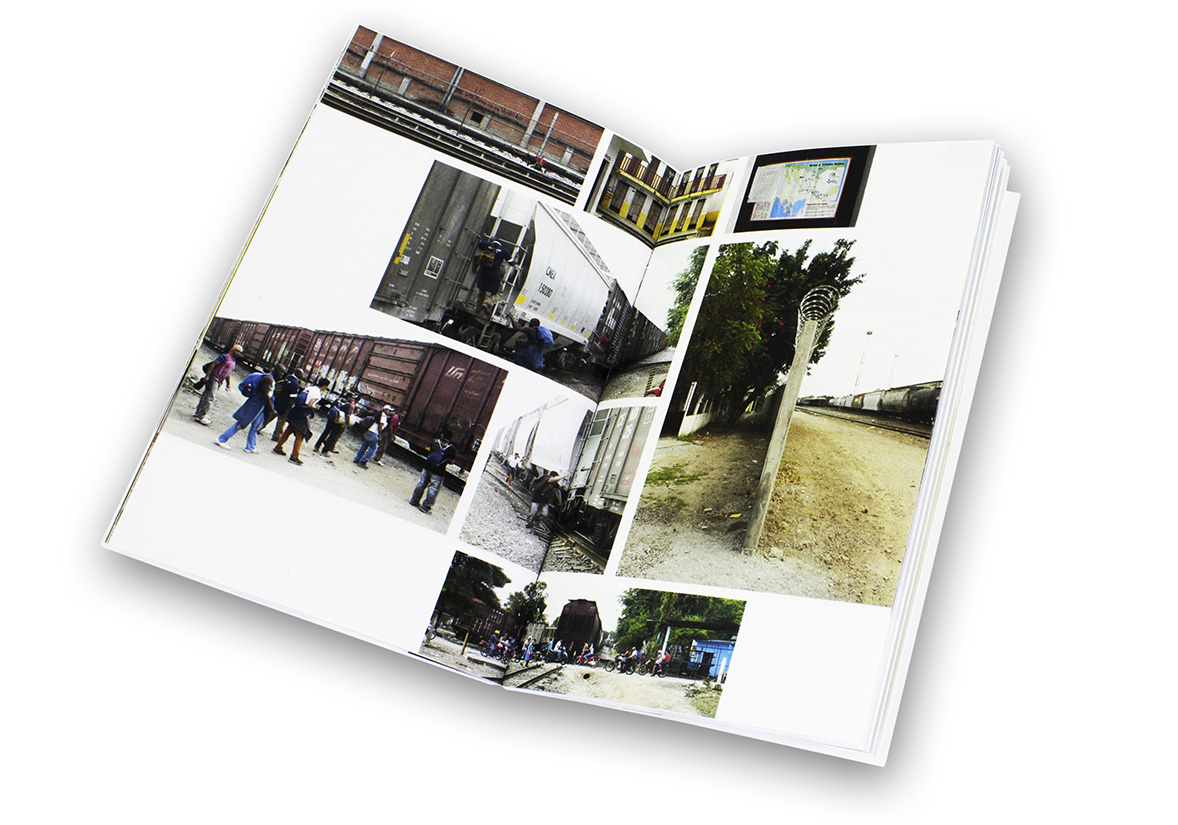

In each city, I explored shelters, hospitals, local residences, train stations, markets, government offices, and other relevant locations tied to the circumstances of each area. During my travels, a close high school friend, then working on a photo essay about wildlife in the Chiapas jungle, decided to join me. This project afforded him the opportunity to delve into a photography field in which he had limited experience, particularly portraits and urban landscapes, while simultaneously learning more about The Beast.

Our method of exploration mirrored the movements of migrants, with our travel plans evolving organically as the days progressed. We maintained an open-minded approach, seeking to uncover as much as possible and amass a comprehensive territorial database. Over two weeks, we recorded nine audio tracks of moving trains and conducted seven audio interviews with individuals working in humanitarian organizations and government entities. Additionally, we filmed video interviews with nine migrants encountered along the journey and in specific locations. We also documented informal conversations and captured videos of various noteworthy events, such as activities within migrant shelters and the official border crossing between Mexico and Guatemala.

Together, we collected brochures and literature distributed to migrants along the route, in addition to capturing over a thousand photographs related to The Beast and the migratory phenomenon.

Spending multiple days at each stop afforded us the opportunity to identify six prevalent conditions along the route, varying in prominence from location to location. These conditions manifested physically as architectural elements and were influenced by treaties and protocols, but were also shaped by the presence of five actors who, intentionally or inadvertently, facilitated their existence and persistence. Interestingly, these particularities bore a striking resemblance to those found in border areas.

1/

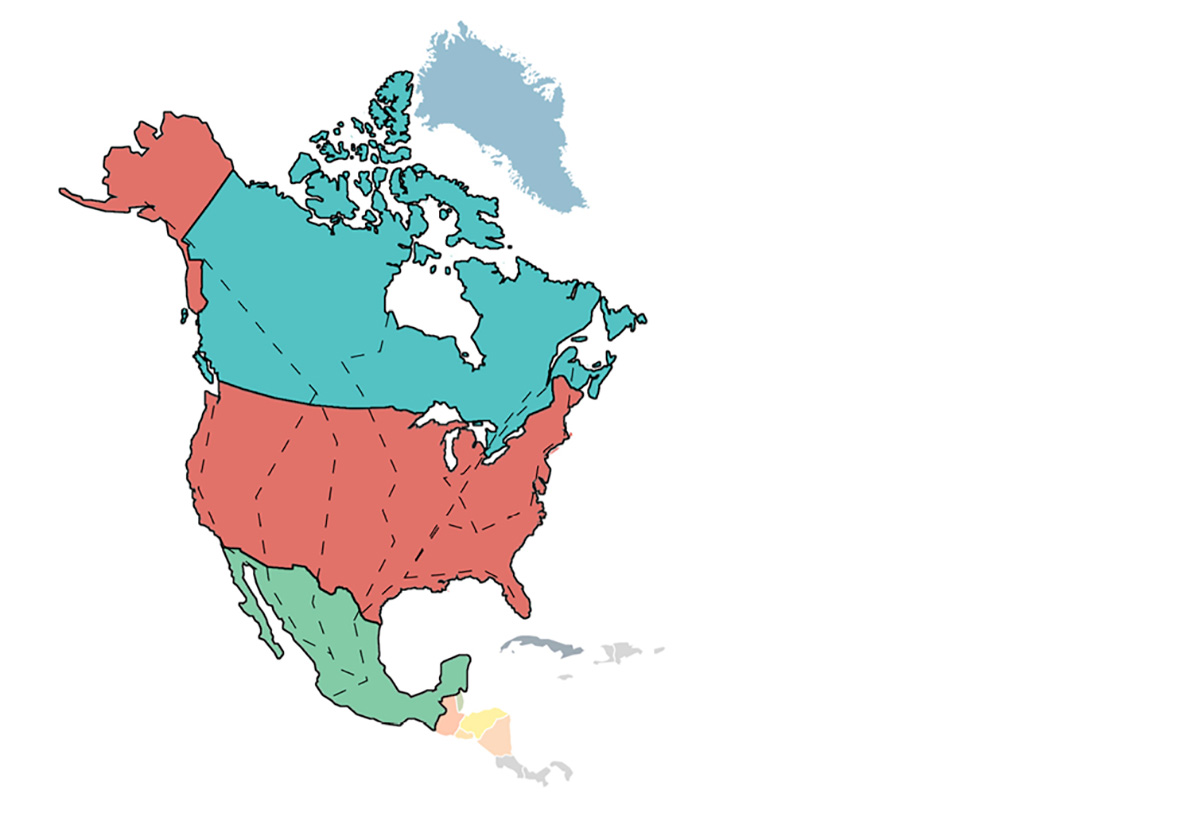

A few weeks after completing the journey, the definitive concept of this thesis became clear: Mexico, in collaboration with the United States, had effectively transformed its official border with Central America into a distributed vertical border. This meant that the typical attributes of a border were experienced throughout the country, particularly along the routes commonly used by migrants. This concept challenged the traditional notion of a border; instead of envisioning a defined line horizontally dividing two countries, we encountered a more diffuse and pervasive boundary.

The overarching aim of the project was to illustrate how these conditions, when manifested spatially, contribute to the creation and maintenance of a complex, vertical border. To convey this, I aimed to produce an easily accessible document with a quasi-propagandistic tone. Given the interconnectedness facilitated by geographical references, I conceived of an atlas. Considering that the conditions manifest in various architectural forms of varying scales, I also developed the idea of a catalog. Exploring ways to blend both formats, I concluded that a navigation guide would be the ideal medium for the project. However, my focus on navigation extended beyond mere leisure or pleasure; it was rooted in meticulous planning and a deep understanding of the landscape.

The project ultimately took shape as a navigation guide structured into six sections, each represented by a specific stop that exemplifies one of the six conceptual categories I identified. Each analytical chapter contains a series of maps, ranging from broad scale to detailed locations. These maps were not based on data, but rather on my personal experiences during the journey; tracing them felt like revisiting the studied territories and understanding how to navigate each city while progressing northward.

The accompanying texts offer detailed descriptions of how to reach each point, what occurs during each transition, general observations about the landscape and city dynamics, as well as specific descriptions of the selected locations illustrating each condition addressed. Each condition is developed both theoretically and empirically, drawing from the interviews I conducted and information available from media sources. These descriptions are complemented by drawings intended to represent, in spatial terms, the architectural objects through which the identified conditions manifest.

1/

The navigation guide serves as a conceptual tool not only to elucidate the distributed vertical frontier phenomenon to a broad audience but also to cultivate awareness about an issue transcending mere statistics. I believe that a phenomenon of this nature, with its multifaceted political, economic, and social implications, offers an ideal platform for fostering contemplation on the interconnectedness of space, people, and territory. By delving into the complexities of the distributed vertical frontier, we can prompt meaningful dialogue and provoke critical reflection on the dynamic relationships shaping our world.

This output stands as more than a mere informational resource; it serves as a catalyst for deeper engagement with the intricacies of our ever-evolving global landscape. Through continued exploration and discourse, we can strive towards a more nuanced understanding of the forces shaping our environments and societies.

The Distributed Vertical Border

* Graduate research project

+ Mark Wasiuta (advisor)

¤ Critical, Conceptual and Curatorial Practices in Architecture

¬ Mexico, Guatemala, United States

^ Columbia University in New York

∞ 2016